Alvaro Mejia: I would have liked to have raced in a clean era

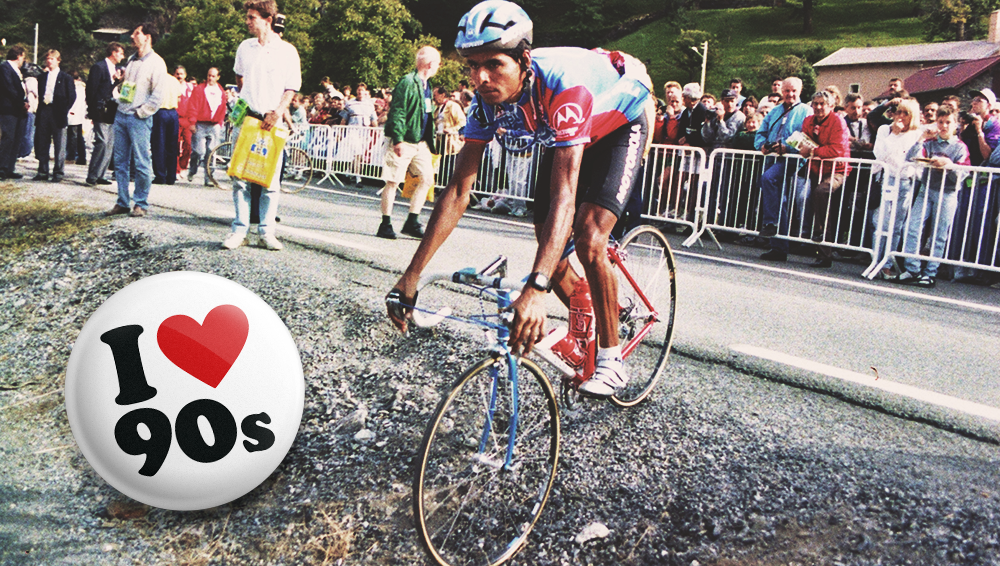

Former Colombian GC contender recalls his breakthrough 1993 Tour de France

The following feature forms part of our 'I love the 1990s series' and sees Matt Rendell track down Colombian climber Alvaro Mejia for a rare interview.

Soon after the then 26-year-old Alvaro Mejía joined Motorola in February 1993, rumours spread through the team. Out training together, Andy Hampsten, who had finished in the top five at the previous year's Giro and Tour, couldn't even stay on his wheel. They had a phenomenon on their hands.

Mejía shouldn't even have been on the team. Modest, quietly spoken and now a medical doctor and university lecturer, Mejía explains why.

"I had a two-year contract with [Colombia soft drinks brand] Manzana-Postobón, but after the first season, the sponsor decided to leave cycling and move into football. A contact of mine tried to create a team in Europe with a tennis racket brand but it came to nothing. Then at the start of the following season Postobón told me that they had reached an agreement with Motorola, who owned a company in Spain called Ryalcao. They would buy space on the Postobón jersey and in exchange I would go and ride for Motorola."

Five months later, after seven stages of the 1993 Tour de France, the wisdom of the trade was clear. Mejía lay second overall. No Colombian had ever been so close to the yellow jersey, Fabio Parra never higher than third, Lucho Herrera never better than fifth. They were the riders who had inspired Alvaro Mejía to take up cycling as a 16-year-old, growing up in the village of Santa Rosa de Cabal, high in Colombia's coffee-growing region at an altitude of 1750 metres.

"Athletics was my first sport. I won a national junior title for 10,000m and the prize was sporting equipment. Since I also played football, I claimed the prize in football equipment. Then one day I saw the Vuelta a Colombia pass. It was 1983 or 1984. Lucho was there, Fabio Parra, Oscar Vargas too. I was impressed by the crowds, but also their time for the stretch between [the towns of] Pereira and Santa Rosa. A week later I started cycling.

"It was a few years before I joined my first trade team, Almacenes y Joyerías Felipe, a team created by a real cycling fan, Rodrigo Murillo Pardo, who was then kidnapped. It was when we were riding a Vuelta al Valle that we were informed that he had been found dead, and the team would be folding."

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Mejía was snapped up by Castalia, the under-23 arm of the professional team Manzana-Postobón. He immediately won the 1988 under-23 Vuelta a Colombia and the elite Clásico RCN. His season could have been even more successful, but, he remembers, "I was leading the Vuelta a Colombia against Lucho and Parra, until I recorded a suspiciously poor time in the final time trial from Villa de Leyva to Tunja. I was told they had decided to stop me winning the Vuelta because powerful interests wanted a professional to win, not an under-23 rider. It was important for the prestige of the race. I don't know if those rumours were true. I never looked into it."

By 1991, Mejía was riding a mixed, and extremely attritional calendar.

"We did the major Colombian races – Clásico RCN, Vuelta a Colombia, the regional stage races in El Valle, Cundinamarca, Boyacá and Antioquia. Then we travelled to Europe for the Vuelta a España early in the European season. It was really hard and very cold. Then we came back to Colombia to race, then returned to Europe for the Volta a Catalunya, some races in Italy, then the Giro d'Italia, Tour de Suisse and Tour de France. We rode a lot."

A lesser physique would have collapsed ("They used to count our race days, not how many kilometres we had ridden," he says). However Mejía thrived. In 1991 he rode his first Tour de France, taking the title of Best Young Rider. At the World Championships in Stuttgart, he finished fourth.

"I joined the breakaway group with Indurain, Bugno and Rooks. On the final lap, Indurain attacked on the climb, but was chased down. Then I made three or four attacks, but they realised that I was strong and marked me closely."

By 1993 Herrera and Parra had retired and Alvaro Mejía was in Motorola colours.

Far too quietly spoken to brag about the tales of whipping Andy Hampsten in training, he will only say: "I remember something like that. I lived close to Lake Como and the Swiss border. Andy lived nearby too, with a family, and Armstrong was about five kilometres away too, but I became particular friends with Hampsten. We used to meet up and train and do specific work."

In the form of his life for the 1993 Tour de France

After winning the Volta a Catalunya in the first part of the 1993 season, Mejía went into the Tour de France having shown physical maturity and excellent form. After one week of racing, he lay second in GC behind Johan Museeuw. Mentally and physically, he was in the form of his life.

"I was very calm. I felt very good. I was on a big, well organised, serious team, well directed, with clear goals and good riders around me, teammates from different countries who were totally committed to working for me. All that together meant I could make the most of my good condition."

Then came the famous Lac de Madine time trial, which Indurain won by more than two minutes. Mejía finished tenth in the stage, a very good result, but still dropped to eighth overall, three minutes and eight seconds behind the Navarran.

"However good you are in any given discipline, you always have that doubt about how you are going to ride with so many kilometres in your legs, and at the Tour we were doing very long, hard stages of more than 280km. Today, the distances, and other things too, are far more controlled. I felt good, but there were other time trial specialists who did a bit better than me."

Two days later, Tony Rominger, Mejía, Indurain broke away together on the mountain roads between Villard-de-Lans to Serre Chevalier. Mejía's disadvantage of 3:08 was unchanged, but the six riders lying between him and Indurain (Eric Breukink, Johan Bruyneel, Gianni Bugno, Bjarne Riis, Johan Museeuw, and the Polish rider Zenon Jaskuła) all lost significant time. Mejía was second again.

He remained there for the following nine days. Below him, however, the general classification evolved. Jaskuła, third after Serre Chevalier, a minute and 12 seconds behind Mejía, won stage 16 at Soulan Pla d'Adet while Mejía hemorrhaged time.

"I didn't know that stage finish, and before the final climb, there was a long descent, and most of the cyclists rode pedalling and braking in order not to get too cold. And I didn't worry about it, and I reached the foot of the final climb with cold legs. It's not a good situation: the cold can lead to all sorts of muscular and physiological problems, and that's what happened," he explains.

"Rominger was the first to attack, Indurain got on his wheel, and I followed Indurain. But I could already feel the muscles swollen. I started the climb too cold, and I paid the price. I lost a lot of time. Hampsten had been dropped, but he caught me and helped me and encouraged me all the way up the climb. He was the perfect teammate all Tour, but especially that day."

Mejía finished the stage seventh, shepherded home by Hampsten. Jaskuła now lay just 14 seconds behind the Colombian, and Rominger too had scythed through the general classification. The Swiss rider had jumped into fifth place at Serre Chevalier, won stage 11 at Isola 2000, finished second in stage 15 (231.5km from Perpignan to Pal/Andorra) and second again the following day (Andorra to Saint-Lary-Soulan Pla d'Adet, 230km).

On the morning of the decisive final time trial, Mejía lay fourth, 59 seconds behind Jaskuła and one minute, 13 seconds behind Rominger.

On the start ramp in Brétigny-sur-Orge, with the 48 km test to Montlhéry ahead of him, Mejía was still confident of finishing second in the 1993 Tour.

"I'd beaten Rominger in the time trial at Lake Annecy three years before. Jaskuła was a good tester but he didn't frighten me," he says.

"Of the specialists, he was probably the worst. I felt very comfortable riding against the clock. I had a good position on the bike, which is very important because it allows you to concentrate on the road, the gearing, the technical aspects. But that day, I remember, after 15 or 20km, my sunglasses started to irritate me and I had to jettison them. That had never happened to me before. I started feeling very uncomfortable in the saddle. The result was probably the worst time trial of my career."

"As I approached the finish, I was feeling bad and my head was full of doubt. My only hope was that perhaps Rominger or Jaskuła had had a bad day too, and I could keep my podium place. Then my directeur sportif told me that my time was not enough for third place. The podium had gone."

"It was," he says, with typical understatement, "a shame."

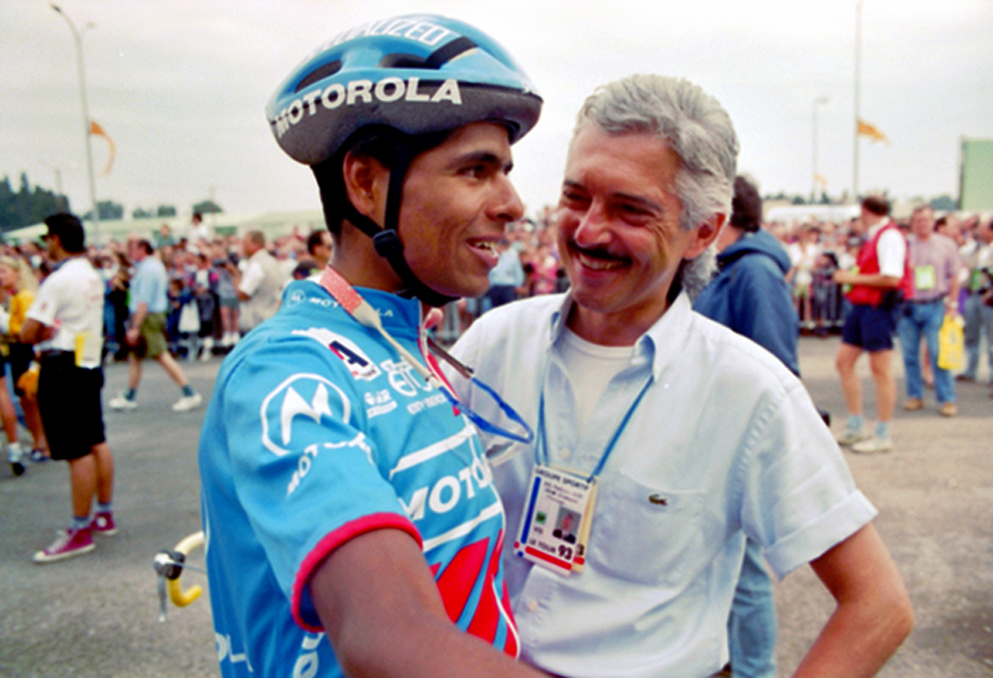

Álvaro Mejía finished the 1993 Tour fourth, seven minutes 29 seconds behind Miguel Indurain, with Rominger second and Zenon Jaskuła third.

Reflections on the impact of EPO

It was the highpoint of a career that ended early.

"I rode for two more seasons with Motorola, then I did one more season with a Colombian team called Petroleos de Colombia, the creation of the Minister for Mines, although he left his position soon afterwards and the team was terminated. With that, I finished my road career."

Two more seasons as a mountain biker followed, before Mejía gave up professional sport, went to university and, after seven years of studies, qualified as a doctor. In recent years he has lectured at the Universidad Tecnológica and the Universidad Andina in Pereira.

Mejía is on record claiming that he was offered EPO during his career but refused it. When that claim is mentioned, but not before, he confirms it.

"When I was a rider, I heard and read about things that were going on, but I was always very sparing in my use of medicines. I have always thought that sport should be clean and health should come first. Instead of using EPO, I thought seriously about retirement. There was no support in those days from WADA or the UCI. It was only three years after I retired that they began to test for it."

"It often used to be said that, without the old, prohibited methods, it was impossible to be a contender in the Tour de France. I know it can be done because I did it. I rode lots of Grand Tours. I didn't win because, as my doctor told me at the start, 'You are riding with a tremendous disadvantage with respect to the others.'"

But is this really looking back, or is it reinventing the past? After all, EPO was certainly in common use by 1993, and in that year's Tour de France Mejía matched and often bettered the likes of Rominger, Riis, Jaskuła and Indurain. By 1994 EPO was certainly current at the Motorola team. In all probability 1993 was no different. [Ed. several Motorola riders, including Lance Armstrong, Bobby Julich, and Frankie Andreu have admitted to doping at the team in the 1990s].

The fact is, as he says, the test data that would either corroborate or disprove his claim is lacking.

However Álvaro Mejía's version of the past is to be interpreted – and any optimism should probably be tempered by a healthy dose of intellectual pessimism – he is certainly sincere in his regret of the circumstances in which he was forced to ride.

Today, as a qualified medical practitioner, he rightly celebrates the more recent breakthroughs in anti-doping science and procedure. Rejoicing in the end of untrammelled EPO use while also, perhaps, lamenting the passing of youth.

"The current controls are a blessing in disguise for the riders. I wish I could have ridden today: I would have liked to have ridden in a clean era," he concludes.