Alberto Contador: The real star of the Vuelta

Procycling magazine looks at El Pistolero's refusal to bow out quietly

Procycling November 2017 is now available in UK newsagents and you can subscribe here.

The Vuelta a España was the final race of Alberto Contador's career and on home roads, for the last time, he unleashed an onslaught of attacks before securing a fairytale win atop the legendary Angliru. Procycling magazine looks at El Pistolero's refusal to bow out quietly

Stetina: Contador's last Vuelta a Espana is like Michael Jordan's last game

Contador ends career with fairytale solo Vuelta a Espana stage win

Contador: Being stripped of 2010 Tour and 2011 Giro was a 'tremendous injustice'

Mollema: It's a pity for cycling that Contador retires

Contador calls for ban on power meters in competition

Froome and Contador to headline China and Saitama criteriums

At 10pm on the final Sunday of the Vuelta a España, the overall winner Chris Froome was taking questions in the race's mobile press centre, an inflatable pavilion erected just a stone's throw away from the finish line on Madrid's Paseo de la Castellana boulevard. But his answers were all but being drowned out by the racket made by the thousands of fans in the square outside. A full two hours after the stage had finished, they were still chanting, "Contador, Contador, Contador".

Froome might have conquered the Vuelta at last. But the deafening noise outside the press tent showed clearly which rider had conquered the hearts of the fans: Alberto Contador.

Contador's Vuelta was his swansong, but he hadn't treated it as a victory lap, or photo opportunity. He showed his attacking spirit right up to the last stage possible and went out in considerable style, riding into the sporting sunset with a victory on Spain's iconic Alto de l'Angliru. It might have looked like he was going down all guns blazing, but his rearguard action proved successful. Froome admitted he was impressed. "It's pretty romantic and commendable what Alberto did today, being his last ever race and he's so competitive and so fierce up the front," he said on the evening of that stage, the race's penultimate. "What a way to end his career. If I can do that when I decide to call it quits, I'd be chuffed to bits."

The final victory salute of Contador's career – his usual 'pistolero' cocked and fired gun - also felt like poetic justice after three weeks and a blizzard of attacks. They became more and more frequent, the closer he came to the end. Of the 11 different Vuelta stages where Contador blasted off the front, eight came in near daily succession from stages 11 to 20. He was off the front of the race for a total of 101km, 38 of them alone. That might not sound much, especially in a season when Lotto Soudal rider Thomas De Gendt spent 1,280km in breaks at the Tour de France. But De Gendt is a breakaway specialist, Contador is a GC contender and has a lot less leeway than riders who are in the lower reaches of the overall classification.

In the final 10 days of the Vuelta, discounting the time trial at Logroño, Contador only spent two days in the peloton from start to finish: the rolling stage to Tomares won by Matteo Trentin, and the final stage in Madrid. On stage 18 on the second category Collado de la Hoz Contador attacked no fewer than seven times. "I've promised Froome I won't play with his balls for at least two days," he promised with a grin at the finish, before promptly attacking on a third category climb 24 hours later. He was irrepressible.

The Collado de la Hoz of course was where Contador forged his legendary long-distance attack to Fuente Dé and victory in the 2012 Vuelta. Once asked to describe why he had started that move, Contador said, "I felt like I had an angel on one shoulder, saying 'Play it careful, wait to attack,' and a devil on the other shoulder saying, 'Go for it, you've got nothing to lose.' I listened to the devil."

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In the 2017 Vuelta Contador seemingly only listened to his inner demons for the entire three weeks. In fact, apart from the stomach problems which put him out of the overall running on stage 3, he looked to be at his strongest in a grand tour since the 2015 Giro d'Italia, which was his last GC win in a three-week race.

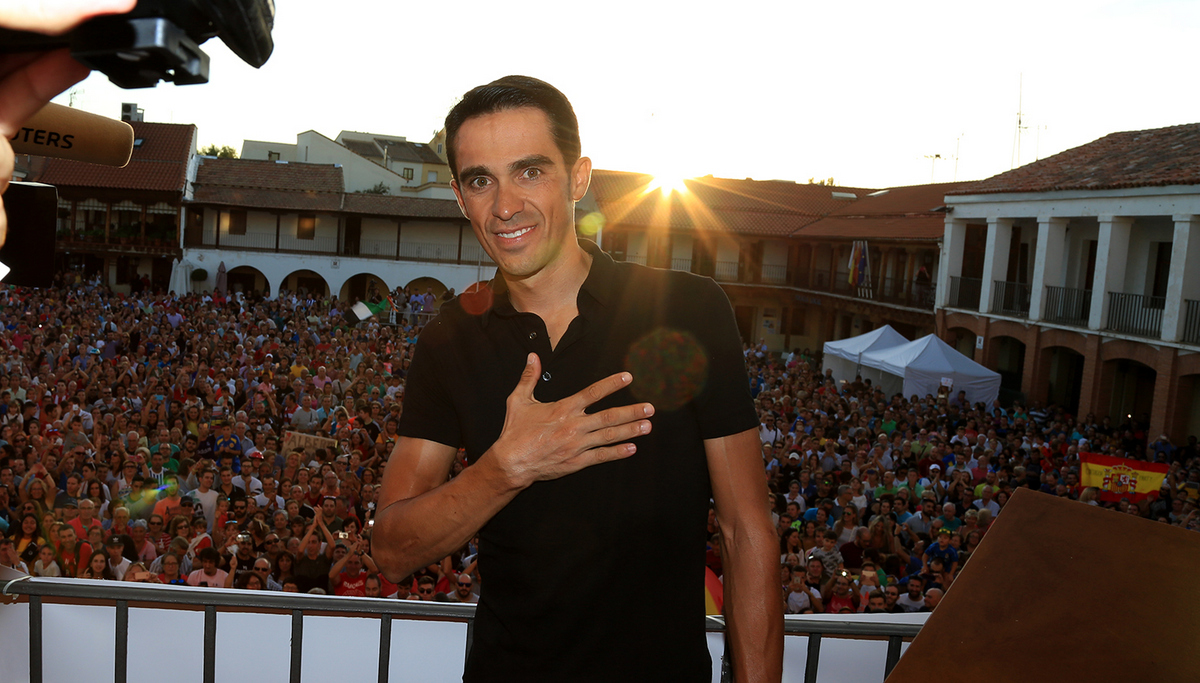

Yet even had he not constantly attacked, Contador's level of popularity in Spain at this year's Vuelta was among the greatest seen in a recent grand tour, save perhaps Richard Virenque in the 1997 Tour at the height of 'Virenque mania'. In Spain 20 years later evidence of Alberto-mania was everywhere: from the hundreds of roadside banners and posters demanding 'One more year' and 'Stay, Alberto', to the crowds 15 or 20 people deep outside the Trek-Segafredo bus on each stage. If this was the end of an era, as it was so often described, then everybody wanted to be a part of it, not just the fans. "It's like being on the team when you're playing Michael Jordan's last ever game," Contador's Trek-Segafredo team-mate Peter Stetina told Cyclingnews.

Each day, half a dozen policemen were needed to escort Contador through the crowds, and each day Spanish sports dailies like MARCA would carry a special page-wide section devoted exclusively to the countdown to Contador finally finishing his career. "Every time Contador attacks, an electric shock runs through the country," said one of Spanish cycling's best-known bloggers, Joan Seguidor. "The population gets fired up, Twitter goes mad and the voices of the television and radio commentators get blocked up with emotion." The stage of the Angliru, with a 20.5 per cent television audience share, was the highest rating the race had achieved in 15 years.

Tellingly, it took a non-Spanish journalist - Matt Lawton of the Daily Mail - to write of dismay at Froome's praise of Contador and his own "wincing" at Spain's outbreak of "joy" at Contador's success. However, Lawton's pertinent reminders of the shadows surrounding both Contador and Froome's scandal-hit Team Sky, were in the minority. Because it wasn't just the fans and riders who praised Contador to the rooftops: at least one journalist on the Angliru summit was in tears as Contador crossed the finish line, triumphant for one last time. "An immortal hero," gushed the respected Spanish daily El Mundo. "He is El Duende of the Vuelta," said the usually equally solemn, straitlaced El País, an untranslatable word used mainly to describe the most intense moments in flamenco music, where the dancer or musician suddenly becomes blessed with semi-divine inspiration. “Whether you're from Pinto or [Flamenco heartland] Trebujena, having duende is not something just anybody can aspire to," El País insisted.

Yet amid all the Contador worship, his riding up and down the Castellana draped in a Spanish flag, and the broader admiration of the Spaniard's "courage and charisma" (as another British sports journalist wrote during the race), there was one underlying question for all of Contador's fans and detractors. It was understanding what Contador was trying to achieve in this year's Vuelta: a podium place, the overall victory, a stage win or simply what he called el espectaculo - the spectacle? When Contador listened to his personal demon here in 2012, it had clearly been with the goal of sinking Joaquim Rodríguez and taking the race lead. But what about this time round?

He certainly could have done with some kind of win to go with all these epic gestures. The harsh reality for Contador was that in terms of victories, the Vuelta really was El Pistolero's last-chance saloon. Before the race began he was still without a win during the entire 2017 season and, indeed, with no grand tour stage wins since 2014. Yet the harder he hit cycling's equivalent of the goalposts, the more we were reminded that he had failed, as yet, to score.

Contador's dramatic long-distance attack on Sergio Henao in Paris-Nice in March was arguably his most striking 2017 defeat. But he also lost the Vuelta a Andalucía by one second, and finished as runner-up in the Volta a Catalunya and Vuelta al País Vasco. The Tour de France had seen him deliver some memorable and even significant attacks, most notably with Mikel Landa en route to Foix. But the injuries sustained in a crash on the stage to Chambéry had left him on the back foot, and it was hard to avoid the sense that while Contador continued to blaze with the same dramatic energy as ever, his best days were fading in the rear-view mirror.

The Vuelta initially produced a similar sense of a man out of time. Contador's sudden collapse to Andorra, as early as stage 3, lost him more than two and a half minutes to Froome and put him out of the running for the GC. There were rumours then that he would quit the race.

Yet as Contador admitted later, being effectively out of the GC struggle gave him considerable room for manoeuvre. No longer considered a significant danger by Froome, and even occasionally touted as a potential ally, Contador was able to attack almost as and when he wanted. But still the cynic or realist in the audience could ask: so what? For the first fortnight, Contador's once-feared long distance attacks, such as the one en route to Sierra Nevada, put only a little pressure on Froome. And there, humiliatingly, it was Froome's Sky team-mates Mikel Nieve and Wout Poels, not Froome in person, who reeled Contador in.

Before the third week, Contador's most effective moves came when they caught his rivals napping. On the Puerto del Garbí on stage 6, a little-known ascent in the province of Valencia, Contador not only lined everybody out, he turned what looked like a fairly dull medium mountain stage into one where Froome had to defend himself. At Antequera on stage 12 his late move over the Puerto del Torcal could, had Froome's crashes been more serious, have put Contador back into the GC game with a vengeance. Having sprinter team-mate Edward Theuns up the road to tow Contador along the shallow descent to the finish was a strategic masterstroke. A general lack of strong team support had been a constant woe of Contador's since his days with Astana, and he knew he was unlikely to beat his rivals through brute force alone.

After Antequera the attacks came thicker and faster, along with the strategically planned ones like into Gijón on stage 19, again with Theuns to tow him, and with Jarlinson Pantano on the descent of the Alto del Cordal and onto the Angliru.

"Everybody's legs hurt, even Sky's," would be Contador's defence for his inability to stay inside the peloton even for one day. Was attacking for the hell of it such a bad thing? In some ways it feels churlish to criticise Contador's gleeful tearing up of the script, when for year after year teams like Sky are slated for calculating all the spontaneity out of the racing, as some fans see it.

Froome, of course, gets top marks for tenacity, stamina and courage. While the Briton and Sky's devastating show of strength as early as Andorra left little room for doubt as to who would probably be the final winner in Madrid, he was constantly under pressure given the small margin of his lead. Equally, his willingness to sit down and take questions from the press every day earned him a round of applause and expressions of appreciation from the media at the end of the Vuelta.

But as rival after rival self-destructed and Froome stayed as ever in control, Contador certainly provided the entertainment in what was otherwise a singularly predictable Vuelta, where one had the feeling that Froome and Sky applied exactly the same winning formula that has made the Tour a one-team show for most of the last six years.

If Froome was the Vuelta's head, Contador was all of its heart. And his scattergun attacks trended towards being increasingly effective. At Alto de Los Machucos, where Contador lit the fuse on the attacks that saw Froome at his most vulnerable, he took more than a minute from the Briton, the biggest gain of any GC contender on Froome by a long way. Come the Angliru, where he accurately interpreted Froome's caution on the previous descent, he broke away before the foot of the final descent with Pantano and gained the 30-second margin that effectively netted him the stage victory, the most coveted of the Vuelta.

At which point the whole exercise suddenly mutated into a glorious overcoming of almost impossibly long odds. Contador described it thus: "The perfect ending to my career."

Procycling November 2017 is now available in UK newsagents and you can subscribe here.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.