Aero ruling - the manufacturer's view

Technical director at component manufacturer 3T, Richard McAinsh, recently contacted Cyclingnews...

Tech feature: Manufacturer responds to aero rule changes, March ?, 2009

Technical director at component manufacturer 3T, Richard McAinsh, recently contacted Cyclingnews with some thoughts about the aero rules that threatened to cause havoc at the Tour of California.

Whilst we heard the opinions of team managers and the UCI, the views of manufacturers, who invest heavily in new equipment at the highest level, went largely unpublished. Despite receiving a stay of execution for teams in California, those in McAinsch's position must now look towards the future and make tough decisions relating to a company's response to the rule changes.

Sponsorship deals with the Garmin-Slipstream and Cervélo squads mean that the stakes are high for a company that only produces components. The visibility of these arrangements is vital to the business, so any rule changes that may compromise these relationships are vital to the company's health.

Exactly when the UCI will begin enforcing the rule clarification is still in question - estimates range from UCI president Pat McQuaid's "very soon" up to the 2010 season. Even at best, though, that gives the likes of McAinsch less than a year to develop solutions that will enable teams such as Garmin-Slipstream, which uses 3T's Brezza aerobar, to continue its relationship with the company into next year.

Below is Richard McAinsh's letter in full:

Sir,

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

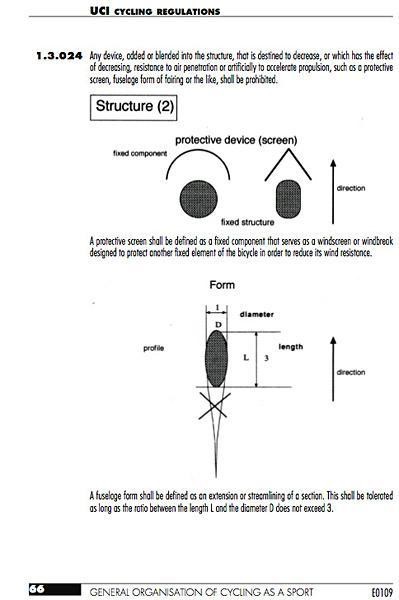

I would like to take this opportunity to put a few thoughts down regarding the situation that arose at the Tour of California on the interpretation of rule 1.3.023 and particularly 1.3.024.

I would like to offer our insight as a manufacturer very caught up in the debate into how we see things. Maybe being new to the industry and the sport we can put these points forward without prejudice or being seen as having an alternative agenda of some sort.

The rules

*When we reformed 3T in 2007 rule 1.3.024 was already being enforced.

*We consulted with industry specialists to help ‘kick off’ our initial product designs, including the Ventus aerobar.

*A competitive analysis of similar products in the market, and being raced, showed us that very few, if any, adopted an interpretation of rule 1.3.024 whereby the fuselage form applied to handlebars.

*Anecdotal evidence suggested that neither the teams, riders or other industry insiders regarded rule 1.3.024 as applying to handlebars.

*One argument that might support this view is that rule 1.3.009 specifically isolates handelbars as part of a ‘steering system’ and thus it might be argued that they fall outside the definition of ‘frame’ used in rules 1.3.020 an 1.3.021 or the definition of ‘structure’ used in 1.3.023 and 1.3.024.

*Rule 1.3.023 specifically refers to ‘traditional’ handlebars reinforcing the notion that handlebars may be regarded as separate items.

The background

*On a personal note I have a lot of experience of this kind of rule interpretation in dealing with the FIA, the governing body of motorsport.

*At a meeting with the UCI we discussed the Ventus in some depth, based mainly around the issue that it would not fit the stems of the track bike frames adopted by the UCI.

*We asked specifically about compliance with the UCI regulations as we had customers asking us this very question.

*We were not given any indication at that time that the Ventus presented a problem (I would emphasise we were not given any clear approval).

*This seemed to us to fit with the industry consensus we had found, and so we concluded that the Ventus was OK.

*This bar raced during 2008 on the Pro Tour with Team CSC.

*It was also used by several athletes in the Olympics, (road and track), and the World Championships in Varese.

*On this basis during 2008 we developed a second aerobar (Brezza), which was to a large extent driven by our conversations with the UCI; we were keen to be able to offer a bar that would suit the needs of, and fit the chosen frames used by the UCI.

*You will understand, given our view to this point, why we did not regard rule 1.3.024 as critical to the design of the Brezza.

*This bar was then produced and presented at Eurobike at the end of August.

The teams and timeframe

*The Brezza was adopted by Team Garmin Slipstream for use in racing for the 2009 season.

*After the CSC experience in 2008, the Cervélo Test Team chose to continue with the Ventus aerobar for racing in the 2009 season.

*These two bars represent a massive investment for a small, effectively start-up company, trying to support and promote cycling. It does us no good to make components that would harm cycling as a competitive sport.

*In January we received, (not from the UCI), an e-mail stating that rule 1.3.024 would now be applied to seat-posts and handlebars.

*Given that our product development time for a component like this is typically nine months we were in no position to react prior to the end of the 2009 season.

*We are happy to respect the rules, however, all the implications (commercial and sporting) of such seemingly arbitrary decrees from the governing body must be seen to have been understood. In this instance I can find nobody that thinks this is the case and as a result the UCI alienates teams and the companies like ours trying to support the sport they govern. You lose a great deal of credibility as leaders.

We fully appreciate, and support, the goals of the Lugano Charter of 8th October 1996. They inherently underpin our position as a business; the market for extreme and radical forms for individual elite athletes gives us a market measured in single components. Not a good business model.

Indeed our products, particularly the Ventus have been criticised in some circles for not allowing enough adjustment to fit a wide range of athletes. We are working to address these issues with our new designs. This broadens the market appeal of our products, and in so doing supports the very issue of cycling for all.

We now need to deflect attention from this to make changes to the profile of our bars to comply with the new interpretation of 1.3.024. We need to invest considerable sums to re-tool in a much-reduced product development timeframe so we can support our teams with UCI compliant equipment, for a date defined only as ‘very soon‘ by the UCI president. We also need to consider the cost to write down existing stock if this becomes illegal for UCI-sanctioned events.

Applying the thinking of the Lugano Charter to the current situation:

*As we have established above, rule 1.3.024 has, for at least two product development cycles, (18 months to two years), been regarded by industry as not applicable to handle bars.

*No wildly extreme forms have resulted, certainly amongst commercially available components.

*Rider position is largely controlled by the combination of the existing rules, even taking into account the, ‘bars excluded’ interpretation of 1.3.024.

*Why then did the UCI take the decision to upset the status quo and issue the interpretation reinforcing, (what I accept was their original intention) of inclusion of the handlebars?

*The evidence would suggest that the (industry) accepted interpretation did not conflict with the intent of the Lugano Charter of 1996.

I have seen the issues raised in support of the latest interpretation as to limit cost of development. This is can only be applied as a valid argument to cases where the component is not going to be offered to market. The equipment of Great Britain Cycling for example. In this case they spend their resources developing equipment for a few select athletes without regard to recouping those costs. The resulting dominance of Great Britain Cycling on the track is clearly contrary to the ethos of the Lugano Charter. Yet the current reaction to the rules of the UCI does not prevent this situation.

A catch all regulation serves to harm those commercial enterprises, like 3T, where we very much need visibility on where those costs will be recovered. There is a finite limit to what the market will stand for the cost of a component. This serves to self limit our development costs and we need to think carefully where our resources are spent to achieve the balance between product performance and cost to the end user.

With a tight interpretation such as now being applied to rule 1.3.024 our ability to distinguish our product from our competitors becomes more difficult. The net result is that costs go up as we seek to find that, now very, small area where we can get a tangible product improvement to offer our customers. The ‘performance development only’ case of Great Britain Cycling then increases the gap between their equipment and that of the commercially driven developers such as ourselves.

Tightening of the regulations on component design will not reduce the time each team spends in the wind tunnel. They perform this work to fit the riders to the equipment. Indeed, by narrowing the opportunity for component designs to distinguish themselves with a tightening of the regulations on form factor, the teams will likely have to spend more time on each individual athlete to get the edge they are seeking. Costs will go up.

Cycling is unique in many ways but, (for me as an engineer), the most interesting from a competitive point of view, compared to other top end ‘equipment reliant’ sports such as F1, is that we can purchase and ride exactly what our pro heroes use. In many cases we can put together improved equipment!

If we consider cost control on innovation; legislation requiring that a minimum quantity be produced before it is permitted to race will focus the attention on cost. It also manages the cases like Great Britain Cycling, they would need to consider an aftermarket before committing considerable industry resource to developing non-commercial components that do not support the spirit of the Lugano Charter.

With the Lugano Charter it seems the biggest concern of the UCI is to maintain a conventional and traditional rider position, with the admirable goal of maintaining the bike as something for every rider.

Would it therefore not make more sense to define a set of anthropomorphic regulations defining rider fit and leave equipment free?

If we imagine a side view of the rider and define a simple set of lines, (head through hip, hip to foot etc) it would be relatively simple to define a range of angles, (based on anthropomorphic models and 95 th percentiles etc) between, torso, hips and arms defining an envelope of acceptable rider positions.

This is then independent of rider size, so does not discriminate between riders, small or large, male or female. It is easy to police; the riders sit on their bikes in front of a grid and have their pictures taken, mug shot style.

This meets the UCI goal of making bikes fit for all and fits our goal of eliminating equipment from their control. Does this make sense to anybody else?

With best regards,

Richard