25 cycling personalities of the past 25 years

The people whose qualities, quirks, antics and accomplishments have made cycling compelling in the past quarter century

This year, Cyclingnews celebrates its 25th anniversary, and to mark such an important milestone, the editorial team will be publishing 25 pieces of work that look back at the sport over the last quarter of a century.

Professional cycling would be nothing but helicopter shots of tiny cyclists and soaring mountain scenery were it not for the larger-than-life personalities of its stars and water carriers.

The Cyclingnews editorial team selected 25 of the most outsized personalities from the past 25 years to celebrate during our 25th anniversary. They are presented in no particular order.

Mark Cavendish: Prolific sprinter who divides opinions

While there's a number of road and track sprinters whose gentle, off-bike personas completely belie their aggression on the bike, Mark Cavendish could often be as quick and angry off the bike as on it.

Not that he doesn't also have a softer side to him, which he's also frequently dropped his guard to show, often to talk about his wife or children later in his career, but it's a world away from turning to his team soigneur to demand to know where his "f*cking trainers" [sneakers] are midway through an interview immediately after winning a stage of the Tour of Qatar.

"You look at the replays of my wins at the Tour, and I'm the fastest sprinter. I'm stating a fact," he told me for Procycling magazine in 2008 after having won four stages at the Tour de France. "I don't know how that can be seen as arrogance when it's just telling the truth. But people can take me as they want. I don't give a shit, really."

It was a mantra he'd use for much of his career – and he was often entirely justified to do so as his Tour stage wins ballooned to 30 over the years, and he added victory at the 2009 Milan-San Remo, the 2011 road race World Championships title and 15 stage wins at the Giro d'Italia, among many others.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The fact that he's always played chess and done Sudoku puzzles to stay sharp for the bunch sprints hints at a busy, creative mind, but the wins have dried up on the back of suffering with the Epstein-Barr virus in recent years, and he told The Times earlier this year that he was diagnosed with clinical depression in 2018.

He was finally given the all clear from Epstein-Barr in April 2019, and promptly took third place on a stage of the Tour of Turkey the same month, but it remains his most-recent result of note since his last win on a stage of the Dubai Tour in February 2018.

Cavendish could still be about to announce that he's joined a new team for next season, or there could be an imminent announcement of his retirement. Whatever happens, few could deny that professional cycling will be a lot less colourful when he does hang up his cycling shoes. (EB)

Peter Sagan: Why so serious?

For a few years, Peter Sagan could barely make a cup of coffee without creating a storm in a teacup. We've got a video to prove it: camera lights flashing incessantly as Sagan works an espresso machine at the 2018 Tour Down Under. At the same race, people went mad for a video of him folding up a finish-line banner to help out the organisers. Looking back, that was peak Sagan. Everything he did – even the most mundane of actions – was greeted with mass hysteria and a viral video.

His star status was built on a platform of Hulk celebrations and off-beat interviews, although he was set back when he pinched the backside of a podium girl at the 2013 Tour of Flanders. An aggressive, no-tomorrow racing style helped to recover his reputation, which was actually enhanced by a lack of success as he endured a string of brave-hearted near misses at the 2015 Tour de France. With his uphill wheelies and his use of the Tour points trophy as a mock machine gun, Sagan was seen as a breath of fresh air – as someone putting the fun back into the sport.

He has fun outside of racing, too, starring in numerous videos showing off his skills, whether it was bunny-hopping up stairs, parking his bike on a car roof, or pulling tricks on a mountain bike. Sagan also starred in a series of tongue-in-cheek promo videos in the run-up to his Giro d'Italia debut this year, although the less said about his Grease video, the better.

'Why so serious?' became a tagline, as did 'They laugh at me because I'm different; I laugh at them because they're all the same'.

But there is a serious side to Sagan, and at times it felt like straitjacketing him as this figure of fun has done him a disservice. The taglines, which came along when he won the Worlds in 2015 and 'three-Peted', were accompanied by a logo, book deals, bike collections, and the rest. Sagan became the sport's superstar, but it's hard not to feel that the more his personality has been marketed for corporate gain, the more it has been diluted. (PF, DO)

Philippa York: Inspirational advocate

When I think about Philippa York, the word that comes to mind, above all others, is courage. Courage to become a pro in a difficult era, to conquer European cycling, to scale the mountains of the Tour de France, but, most importantly, the courage to find herself while also battling against prejudice and discrimination.

The fact that York has discovered happiness through going through her transition is inspiring on so many different levels, both to those inside the LGBTQ+ communities, but also to those outside, who, perhaps thanks to Philippa, have a better understanding of those around them.

Like everyone on this list, there are several sides to York's personality – none of us are one dimensional – and a fiery temper as a pro can only be mentioned if complemented by her excellent eye for detail when calling a race or her quick wit when it comes to analysing the sport of cycling.

I have many fond memories of working with her – from the time I almost killed us in a hire car at the Tour de Romandie, to the absolute privilege of reintroducing her to Greg and Kathy LeMond for the first time in over 20 years at the Tour de France.

There was the memorable time I was able to sit in on her interview with Allan Peiper as they talked about the 80s, and of course the countless times she's reminded me not to take anything too seriously. From a pioneering rider to an icon for trans rights and advocacy, York is an inspirational person with an inspirational personality. (DB)

Graeme Obree: Innovator and outsider

"My relationship to cycling is like Pluto's relationship to Earth," Obree once said, but while the comment underscores his status as an outsider, it undersells his impact on the sport.

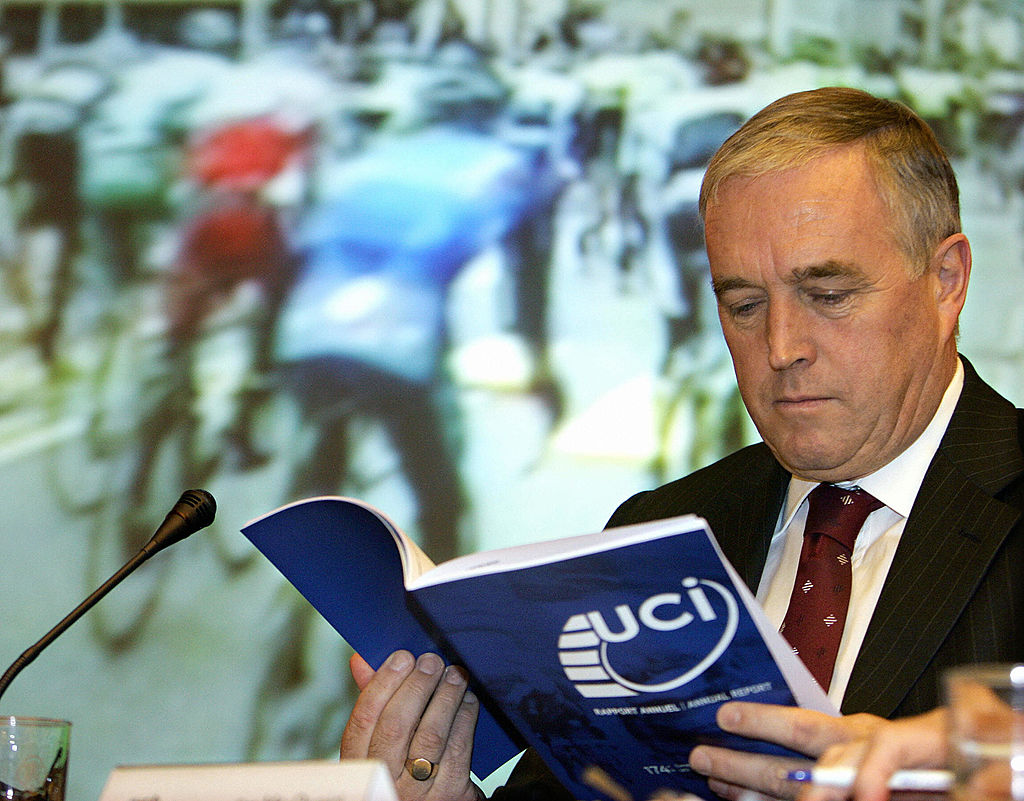

Twice a world champion in the pursuit and twice a holder of the World Hour Record, Obree was one of the finest track riders of the 1990s and one of the sport's greatest innovators. When his initial tuck position on 'Old Faithful' was banned by the UCI, he responded by developing the 'Superman' bike position, which was also later outlawed, but not before it was adopted by both 1996 Olympic pursuit champion Andrea Collinelli and Obree's great rival, Chris Boardman.

With grim predictability, the UCI also took issue with Obree's anti-doping stance, with Hein Verbruggen labelling him a "coward" for highlighting that professional cycling was awash with doping in an interview with L'Équipe in 1996. Verbruggen, of course, was hopelessly wrong: Obree was anything but cowardly. Writing his 2003 autobiography, Flying Scotsman, with its unflinching account of his struggles with bipolar disorder, was an act of immense courage.

Obree remains a committed cyclist and bike builder, creating the 'Beastie' for a tilt at the Human Powered Land Speed Record in 2013. He also published a coaching manual entitled The Obree Way, even if following in the wheels tracks of a one-off is easier said than done. (BR)

Greg LeMond: The only American Tour de France winner

Reading Greg LeMond's blunt assessments of the sport, of doping, of marginal gains, or of his nemesis Lance Armstrong in the press, one might think that beneath these opinions lies a bitter and dyspeptic man. Meeting LeMond in person, however, one finds exactly the opposite. Unlike other top riders who shield themselves with their fame, the three-time Tour de France winner is a mix of California confidence and Midwestern nice, greeting strangers with a ready and unguarded smile.

Affable, open, and intelligent, LeMond can describe in detail every moment of his career and give exhaustive opinions on just about any topic, but none more than on his passion: cycling.

The ever-resilient LeMond now laughs while telling the story of being accidentally shot in the back in 1987 – an incident that could have killed him.

During his ambitious career, he led the way with equipment innovation to famously beat Laurent Fignon in the final time trial to win the 1989 Tour de France, was the first to win the Tour on a carbon bike, and formed his own bicycle brand, which he later licensed to Trek.

An outspoken realist and fiercely principled, LeMond might have been absolutely correct by famously saying in 2001: "If Lance is clean, it is the greatest comeback in the history of sports. If he isn't, it would be the greatest fraud."

But the statement led to the end of his relationship with Trek and his LeMond bike brand. He's laughing last now: LeMond is launching a new e-bike brand this month and, since 2012, can call himself the only American Tour de France winner. (LW)

Floyd Landis: Chaotic whistleblower

Floyd Landis has been many things during his life: Mennonite wild child, Tour de France winner, and then the architect of Lance Armstrong's demise after suffering greatly with the guilt of his own doping. Through it all flowed his love for cycling and deep sense of honesty.

These days, he is busy with his growing Floyd's of Leadville marijuana and cannabidiol (CBD) company, but has earned his place in the Cyclingnews list of 25 personalities for the meteoric impact he left on the sport, especially in the USA.

His 2006 Tour de France victory has been cancelled from the record books, but it was a foreshadowing of Landis' willingness to throw all caution to the wind when down. He will be forever remembered as the one who ultimately stood up to Armstrong's bullying, sending a series of emails that would destroy the façade that existed around Armstrong and exposed like no other the extent of doping in professional cycling.

Landis took the money won through years fighting to prove Armstrong's fraud in the US federal courts and used it to support a short-lived team.

"If I'm taking on Lance Armstrong, then that should be evidence enough that there's a problem with the system, because I'm saying it – a bunch of people did it," Landis said this year. "At some point, people have to tell their kids that Santa Claus isn't real. I hate to be the guy to do it, but it's just not real."

That's one hell of a cycling legacy. (SF)

Lance Armstrong: Confident, charismatic charlatan

If there is one quality that defines Lance Armstrong, it's his unfailing self-belief. In his younger years, Armstrong appeared brash and arrogant, defensive and determined to prove himself. His 1996 near-death brush with cancer rounded those edges a bit, and when he returned and found success, his interviews became more polished, he was more open and his comments more poignant and compelling.

After taking the first of his now-stripped seven Tour de France titles in 1999, Armstrong railed against accusations of doping offences in the French media. "I can emphatically say I am not on drugs," he lied at the time.

But he also truthfully reflected on what his Tour win meant to people affected by cancer: "It proves that it's not a death sentence, that there's hope and inspiration, there's life after illness and life after treatment."

Armstrong's self-assuredness and star-power helped him enormously when it came to lying about performance-enhancing drugs. From that first 1999 Tour and the backdated TUE for cortisone up until his confession on the Oprah Winfrey show in 2013, Armstrong calmly, convincingly and blatantly lied to the press – his only tell being a strange propensity to shift pronouns.

After being accused of doping by Floyd Landis in 2010, Armstrong said, "It's our word against his word. I like our word. We like our credibility."

Fans struggled with the betrayal after his doping confession, and numerous articles attempted to psychoanalyse Armstrong as a narcissist. Since being banned, age, disgrace and therapy have softened Armstrong, and he appears to have become more self-effacing, but still craves attention and he still gets it.

He apologised to many of the people he tried to ruin, but whether he has truly changed remains to be seen. Judging by his final comment this year in a documentary on ESPN – "It could be worse. I could be Floyd Landis... waking up a piece of shit every day" – probably not. (LW)

Marco Pantani: Iconic and tragic Italian

Marco Pantani died from a cocaine overdose on St Valentine's Day 2004, but he seems to live on, especially in Italy, where the success and the excess of his career is still celebrated, rather than regretted and learned from.

Pantani's still unequalled 1998 Giro d'Italia-Tour de France double marked the apotheosis of his roller-coaster career. A year later, he was turfed out of the Giro while about to win again after failing a haematocrit test. He refused to accept he had done anything wrong, and his life gradually spiralled out of control due to drugs, depression and nobody being there to stop him self-destructing.

Pantani was, and still is, admired because he was the skinny, bald-headed, pure-climber David who was not afraid to take on Lance Armstrong and the Goliaths of the Grand Tours. He was physically fragile but steely, defiant, determined, proud and impeccably graceful on the bike.

His sincerity stood out, even when he was supposed to toe a corporate line to please his sponsors. If there had been a way to save him from self destruction, Pantani would probably have confessed and done much to help professional cycling avoid its mistakes of the past.

Pantani's death stopped him from growing old and revealing what really happened during his tumultuous career and the EPO-fuelled 90s. His teammates and friends remain in embarrassed silence, while his mother Tonina fights on, trying to find a reason for the tragic loss of her son. (SF)

Paul Kimmage: Speaking truth to power

Paul Kimmage likened himself to the Salman Rushdie of cycling after Rough Ride's publication in 1990, but a decade or so ago, he might have briefly felt himself akin to the sport's Oprah Winfrey, such was the apparent eagerness of some teams and riders to seek his seal of approval.

The experience didn't last long. By 2012, after publishing a definitive Floyd Landis interview on Nyvelocity.com the previous year, Kimmage was being sued by the UCI and had lost his job at The Sunday Times. In professional sport, telling the unvarnished truth is usually neither popular nor profitable.

There was some solace for Kimmage, however, when an online fund sprang up in his defence. Those who wanted to listen now outnumbered those who wanted him silenced. If Rough Ride's warnings had gone largely unheeded on its initial publication, each new edition found a wider audience – not least because each subsequent scandal, from Festina to Aderlass, only underlined its continuing relevance. (BR)

Bradley Wiggins: Rockstar Tour de France and Olympic champion

Cycling's king of the mods. With his sideburns, scooter collection and Fred Perry polos, Wiggins stood out from the team-issue tracksuit-clad crowd. He was dubbed 'Le Rockstar' by the French, who lapped up his wisecracks and declarations of 'Vive La France'.

On home soil as in France, his popularity far outstripped that of Chris Froome, who, despite his four Tour wins, has never connected with the British public. Wiggins only won one Tour, but it was the first one for Britain, and he shot to icon status in that 2012. He rang the bell for the opening ceremony of the London Olympics, and went on to win Sports Personality of the Year, collecting his award to chants of 'Wiggo!' before telling the crowd there was "a free bar round the back paid for by the BBC".

No one could get enough of him, but, despite all that personality, how much did it reveal of the person? "That reckless, rockstar image stays with you," he said recently. "It takes away from the content of your character and what you really are and what you stand for."

Wiggins seemed to belong in the limelight, but in fact the opposite was true. He has struggled with the trappings of fame, and much of his 'personality' can be read as performance. Still, it was quite the show. (PF)

Nicole Cooke: Champion of integrity

There seems to a be a perception, in the UK at least, that in order to be deemed a 'cool cyclist' you need to have perfectly cultivated sideburns, call your detractors ***** in press conferences, and have your own Paul Smith clothing range, but imagine a world in which coolness or emulation from fans was born from riders who moved the sport forward despite huge hurdles, and who, despite gender inequalities and the pressure to dope, never once wavered from a line of integrity.

It wasn't always pretty, and Cooke herself would acknowledge that at times she pissed people off, but her dream wasn't to appease the status quo or those that deemed women's cycling inferior. She was a trailblazer in the very mould that set athletes like Billie Jean King apart from many of her peers.

What's more, Cooke never failed to call out those for cheating, using her retirement speech to implore fans not to make ex-dopers even richer by buying their autobiographies. Her palmarès was of course outstanding, but what defined Cooke most of all was her will to win and her ethics.

Not only did she accomplish her dreams as a rider, she created pathways that many female British riders still benefit from today. It was her personality, perhaps more than her medals, that made the difference in doing that. (DB)

Jens Voigt: Cycling's comic relief

The famous legs of the German rider brought him much acclaim, on and off the bike. He rode hard, he laughed a lot, and he was clever, trademarking his "shut up, legs" mantra by 2017 and launching a line of merchandise. He even put out an autobiography in 2016: Shut Up, Legs: My Wild Ride On and Off the Bike.

Voigt created the mantra after a Tour de France stage in 2008, when he explained in a television interview how he kept attacking in breakaways each day: "I just tell my body, shut up, legs, and do as I tell you."

His fame spread in the US rather than in his home country, where popular German riders of his generation – some Voigt's teammates at CSC and RadioShack – were part of doping rumours and scandal. Voigt has denied ever doping.

He had 59 career wins and rode the Tour de France 17 times as a pro, wearing the yellow jersey on two occasions. Stage wins at the Tour came in 2001 and 2006, but he's equally famous for races he didn't win as a marked man in breakaways.

After 18 years of attacks, crashes and victory salutes, 2014 was his final season, at the age of 42. At his last Amgen Tour of California, when asked by Cyclingnews' Pat Malach about a 'quiet' week and being in another breakaway, Voigt responded, "What the fuck? A quiet week? I was suffering like a pig every day."

He may have suffered, but he was entertaining with every pedal stroke and interview. (JT)

Cecilie Uttrup Ludwig: Bubbly and unrestrained climber

There are a wealth of words that describe Cecilie Uttrup Ludwig, and we're not talking about superlatives in bike racing. She is definitely a personality, overflowing with effervescence and animation. She's just plain happy, considering herself one "crazy banana" and living up to her positive vibes on social media: "Rule number one, keep it fun."

Still just 25 years old, the Danish rider already has seven pro seasons in the bank and is seeing her efforts pay big dividends. She started 2020 with a new team, FDJ Nouvelle-Aquitaine Futuroscope, but while waiting for a suspended racing season to reboot in late summer due to the coronavirus pandemic, Uttrup Ludwig received a contract extension for two more years, through 2022, before she had toed the line for an outdoor competition.

By the age of 17, she was a silver medallist in the junior women's time trial at the 2012 World Championships, and eighth in the road race the same year. As a pro, she's worn a path to various podiums, from La Course by Le Tour de France to Flèche Wallonne, but it was her 2019 interview after the Tour of Flanders – "PAM! Let's put the hammer down!" – that brought her into the spotlight for good. (JT)

Marc Madiot: Boisterous Groupama-FDJ manager

Admit it: when Thibaut Pinot or Arnaud Démare win a big race, you're already looking forward to the impending Madiot video. You know it's coming. Enough of his madcap celebrations have gone viral to ensure that, when Madiot's around and FDJ are about to win a race, someone will press record.

Can we top the hanging-out-the-passenger-seat, car-thumping antics that accompanied Pinot's first Tour de France stage win in 2012? Or the 15 shouts of "Allez Nono!" that accompanied Démare's same feat in 2017? How about Pinot's win on the Tourmalet last year, and Madiot completely losing it on a packed Pyrenean hillside, screaming at the TV before sprinting off to find his rider? There were no fans at all at the French Nationals this year, but somehow that seemed all-the-more fitting as Madiot hurried off the bus and roared, "Oui! Oui! Oui! Oui!" to an empty car park after Démare's victory there.

No one celebrates quite like the Groupama-FDJ manager, who has been doing this for most of Cyclingnews' existence, having set up the FDJ team back in 1997. The former Paris-Roubaix champion has been known to boil over with anger as well as joy, and there have been tears, too.

Madiot wears his heart on his sleeve and shoots from the hip. A staunch defender of the old-school values of French cycling, his clashes with marginal gains' Dave Brailsford have been another source of entertainment: 'Motorhome, go home', was the brilliant title of a 2015 blog he wrote for us.

Love him or hate him, he's one of the sport's great characters. (PF)

Victoria Pendleton: Olympic gold medalist who hated racing

When Victoria Pendleton burst onto the British track-racing scene at the highest level in the early 2000s, she soon proved that having a niche sporting ability doesn't have to define you: that you can be a powerful, fast bike rider and have other interests in life away from the bike.

Pendleton was always able to convey in interviews that she was far from a one-dimensional athlete, and could talk about family, friends and fashion as easily as she could talk about turning left for a living, as she'd joke her job entailed.

Pendleton proved herself to be a well-rounded person that people could relate to, helping to encourage interest in her sport – although she would admit in a 2009 blog for the Guardian that she didn't always love it.

"There are times when I hate cycling – times when I don't want to even look at a bike," she wrote.

And just a couple of years later, she'd go a step further, telling The Times in 2011: "I've always hated it [track sprinting]. I'm just unfortunately good at it."

Indeed she was, and Pendleton retired after taking the gold medal in the Keirin and silver in the sprint at the London Olympics in 2012. In all, besides her Olympic successes – she also took gold in the sprint at the 2008 Beijing Games – she won nine world titles on the track, and later showed her breadth of other interests by becoming a jockey.

In 2019, she chose to share with the world that she'd had suicidal thoughts following the breakdown of her marriage the previous year, in the hope that her talking about it might be able to help other people with their struggles.

"I've turned a corner," she told the BBC last year. "That doesn't mean I won't be more cautious in the future if I start to feel similar symptoms. But I feel I'd be better prepared, at least." (EB)

Tom Boonen: Belgian rockstar

As a Belgian superstar at the top of the sport from the early 2000s onwards, Tom Boonen was one of the rockstars of cycling – a dominant presence during Classics season and one half of the most celebrated rivalry in the recent history of the sport: that years-long battle with Fabian Cancellara.

Boonen took to his star status as much as anyone, at times partying too hard, having relationships dissected in Belgian newspapers, and driving exotic cars – some of which had more bizarre paint jobs than others.

His 2005 Worlds win in Madrid became a thing of legend in Belgium, not for the manner of his sprint victory, but for the commentary that accompanied it. A remix of Michel Wuyts' call ("Tommeke, Tommeke, Tommeke, what are you doing? Tom Boonen is the world champion… Mother, we're not coming home yet") is still played in parties around Flanders, and it has even inspired a master's thesis based on press coverage of him.

While retired pro cyclists often stay in the sport in the media or team car, or take on a modest career such as selling farm equipment or driving a lorry, Boonen has instead taken to motorsports, racing stock and GT cars around Europe.

From Roubaix to Doha, Sacramento to the Champs-Élysées, Boonen took 122 wins during his 16-year career. But beyond the racing, he was a star throughout Belgium – a celebrity hero and a kind of soap star. In modern cycling, there are few, if any, parallels. (DO)

Alberto Contador: 'El Pistolero'

Rather than having as flamboyant or outspoken a personality as some of the names on our list, Contador was a quieter character, but still one of the defining names of the modern generation of pro cycling.

In an era when racing transitioned from the over-the-top attacking of the EPO era into a more controlled affair, Contador's racing style set him apart, with attacking aplenty and risk-taking, long-range moves in the second part of his career, with his 2012 Fuente Dé ambush at the Vuelta a España one of the most famous stage wins in recent memory.

While his surname is Spanish for 'accountant', and somewhat reflective of his more reserved personality, the 'El Pistolero' nickname he went by was taken from his trademark celebration: the gunshot salute as he crossed the line – a rare statement of flamboyance away from his attacks.

Contador's career saw him suffer a brain haemorrhage, a Clenbuterol ban and an intra-squad battle with Lance Armstrong at the 2009 Tour de France, as well as enjoying 68 'pistoleros', including 22 stage-race wins – seven of which were overall Grand Tour victories.

He remained the same through it all: an amiable and calm presence in the peloton who more often than not let his legs make the big statements. (DO)

Ina Teutenberg: A commanding presence

When Ina Teutenberg talks, everybody listens, and she's affectionately known as 'the boss of the peloton'.

The German cyclist had more than 200 career victories, known not only as a powerful sprinter but as an all-rounder, often securing wins in breakaways and on challenging terrain in stage races. She experienced resounding success with five victories at the Liberty Classic, 13 stage wins at the Giro Rosa, 11 stage wins at the Tour de l'Aude and the Tour of Flanders. She spent most of her career racing for versions of T-Mobile, Columbia, HTC-HighRoad and Specialized-lululemon.

Aside from winning, Teutenberg cared for her teammates and fellow racers, even snatching the announcer's microphone after the 2005 Charlotte Criterium was neutralised after two major crashes, pleading with them to settle down, saying, "It's only money, it's only paper – it's not worth it."

Now a director at Trek-Segafredo, Teutenberg has taken her leadership to the next level as a master tactician, encouraging her athletes to do their best and guiding the team to the top of the Women's WorldTour rankings in 2020. She has an air of authority, of being confident and in control, while commanding respect from those around her. She doesn't just expect the best; she brings out the best in her athletes and team. (KF)

Marianne Vos: Champion and songbird

Marianne Vos is an icon of the sport, and well known for her captivating racing style throughout a 15-year career that has netted her 12 world championship titles and three gold medals at the Olympic Games. She is also a natural leader and a reliable representative for the women's peloton. She's a private person and exudes professionalism at all times.

However, among her strength and stalwart nature is a charismatic and fun side that only her close friends and family, and those in the women's peloton's inner circles, are privileged to witness. And if you happen to find yourself being serenaded by one of the most iconic riders of all time, don't be surprised: Vos loves to sing.

"I sing in the bunch," Vos told Bicycling Magazine in a rare, personal interview in 2014. "I can imagine that's pretty annoying. The other riders don't like it. I pass other riders or a teammate, and it's, like, 'It can only be you. Always singing on the climb. Please do it on the descent, and not on the climb.' It just starts happening. I notice when the others start looking around. Oh yeah, I'm sorry, I'm singing. Sometimes I'm bored and I start singing. Mostly it's just to keep the focus or concentration." (KF)

Thomas Voeckler: Maillot jaune with his heart on his sleeve

You can't even say the name Thomas Voeckler without visions of the Frenchman's facial contortions.

He has been called a hero in France, largely due to his breakaway prowess on home soil at the grandest of Grand Tours, which saw him earn the coveted maillot jaune on stage 5 at the 2004 Tour de France and parade it on his back for 10 days.

After five years of bitter domination by Lance Armstrong, Voeckler's time in yellow finally gave his country something to celebrate. However, he didn't actually win a stage of the Tour until 2009, and then a second the following year. In 2011, he was back in the yellow jersey again, and kept it for nine stages. In 2012, he won two more stages of the Tour – both mountain stages – and took home the polka-dot jersey in Paris as the race's 'king of the mountains' that year.

He won other races, like the 2003 Tour de Luxembourg and the 2016 Tour de Yorkshire, and was twice the French road race national champion (2004, 2010), as well as being the perhaps unrealistic hope of his nation for many years to unseat Bernard Hinault as the last Frenchman to take the overall crown at the Tour de France.

While he never lived up to that status – and Hinault remains France's last Tour winner, in 1985 – Voeckler always expressed his pain and patriotism so well. (JT)

Judith Arndt: German who shocked the world at the Olympics

Anyone who flips the bird while crossing the finish line while winning the silver medal at the Olympic Games road race must have some degree of personality. Normally a reserved and soft-spoken leader, Arndt's obscene hand gesture was so out of character that it caused a mass frenzy among photographers and reporters in Athens.

It turned out that she was so outraged over the selection of the elite women's team representing Germany in the road race at the 2004 Olympic Games that she even appeared to have sat up and not contested the final against eventual winner Sara Carrigan of Australia, and the gesture was squarely directed at the German federation.

The whole scene showed that sport isn't just about results, but involves politics and emotion, and that it can indeed lead to some of the most memorable and lasting moments in Olympic history.

Sixteen years later, that gesture resonates alongside Arndt's greatest achievements in cycling as a 21-time national champion, four-time world champion, five-time Olympian and as a loyal and principled teammate. (KF)

Pat McQuaid: Embattled leader

Most people will remember Pat McQuaid as the embattled president of the UCI, and the one to preside over the fallout of the EPO-era in cycling and the downfall of Lance Armstrong. But McQuaid was not just a bureaucrat; he began life as the eldest brother in a family steeped in cycling, spent a couple years as a pro cyclist who won a few races and represented Ireland at the World Championships. He was, and is still, passionate about cycling, and deeply invested in the sport and its future.

He also courted controversy in his early days, defying an anti-apartheid boycott and racing in South Africa under a fake name in 1976, which earned him a lifetime Olympic ban.

McQuaid transitioned from racing to coaching, running the national team for several years and directing the Tour of Ireland, before launching his career in governance, first as President of the Irish Cycling Federation in 1993, on the UCI Management Committee in 1997 and into the UCI head office in 2005 – becoming the first Irishman to lead a major sports federation.

Both personable and loquacious, stern and hard-headed, McQuaid faced enormous battles in his role with the UCI, butting heads with then-ASO head Patrice Clerc. Rather than wage war behind closed doors, McQuaid preferred to fight his battles in the press, trading barbs in an unscripted and brusque manner.

After his 2013 defeat, McQuaid stayed on the sidelines, riding his bike and running a dog-friendly self-catering inn on the Cote d'Azur. By all reviews, he and his wife Aileen are welcoming and generous hosts. (LW)

Frank Vandenbroucke: A talented, troubled star

Frank Vandenbroucke's peak as a rider was brief, his potential was unfulfilled and his life was cut senselessly short in 2009, yet his legacy endures. The Belgian has been the subject of books and museum exhibitions in his home country, but then his talent and charisma made him a star even before he turned professional, with his uncle Jean-Luc's Lotto team in 1994. He immediately announced his arrival by winning atop Mont Faron at the Tour Méditerranéen, and then brokered a contentious mid-season transfer to Mapei the following year.

Vandenbroucke's career, always laced with controversy, reached its apotheosis when he moved to Cofidis 1999. He won Liège-Bastogne-Liège after telegraphing his attack on the Saint-Nicolas in the manner of Babe Ruth calling a home run, but barely two weeks later, he was arrested for his links to Bernard Sainz, alias Dr Mabuse.

Vandenbroucke returned at season's end to produce a remarkable string of displays at the Vuelta, and he was the overwhelming favourite to win the Verona Worlds in Verona, only to crash and break both his wrists – but still finish seventh.

He never won a race again, and although he reminded the world of his former glories with second place at the 2003 Tour of Flanders, his riding drew less attention than his troubled personal life and substance abuse in the 21st century. Working as a pundit at the 2009 Worlds in Mendrisio, Vandenbroucke had spoken of another comeback. The following month, he was found dead in a hotel room in Senegal after suffering a pulmonary embolism. He was 34. (BR)

Oleg Tinkov: Oligarch who toyed with pro cycling

Professional cycling has endured numerous eccentric investors and sponsors over the years, but Oleg Tinkov was one of the craziest and one of the richest, but also one of the most passionate.

The self-made Russian billionaire first sponsored a Professional Continental team in 2007, signing US rider Tyler Hamilton after his ban for blood doping. The team folded after a year, but Tinkov returned to the sport in 2012, joining forces with Bjarne Riis, as his online Tinkoff banking business grew rapidly. He eventually bought the team from Riis as Peter Sagan joined Alberto Contador as team leader.

Tinkov loved to ride with his riders at training camps and rest days at Grand Tours, and drove his team to try to take on Team Sky. He loved to provoke and divide public opinion with his trash talk and aggressive business style. He was unafraid to publicly criticise his riders if they underperformed, or swear liberally in celebration when they won.

Tinkov dyed his hair pink when Alberto Contador won the 2015 Giro d'Italia, but eventually left the sport in 2016 after he realised he would never be able to turn a profit, having apparently spent €50 million in sponsorship.

"The teams are 80 per cent a toy and only 20 per cent business. It should be the other way," he told Cyclingnews in a farewell interview at Il Lombardia in 2016.

Since leaving professional cycling, Tinkov has continued to grow his Russian banking business, but has also been pursued by the US tax authorities after he floated Tinkoff Bank while allegedly still a US resident.

Obliged to reside in London while contesting the case, Tinkov is also fighting acute leukaemia, but still seems to love the art of the deal, recently pulling out of a reported merger with a rival Russian bank. (SF)

David Millar: The road to redemption

David Millar burst his way into superstardom by winning the opening time-trial stage of the 2000 Tour de France and taking the yellow jersey. But just four years later, French police arrested Millar on suspicion of doping, to which he confessed two days later.

Early success had led Millar to take the next, illicit step, and his career – and his life – would be changed forever. He returned to professional cycling after serving a two-year ban a changed man and a changed rider. He knew he'd done wrong, and wanted to do everything he could to change the sport's future, and to prevent other, younger riders following his earlier path.

He became part of the World Anti-Doping Agency's (WADA) Athlete Committee, and made himself available to the media for comments on everything doping, even as the peloton continued not to learn its lesson. In 2006 – the year of his comeback after his ban – the British rider won the stage-14 time trial at the Vuelta a España, and used the opportunity to state that he was the proof that it was possible to win at the highest level without resorting to doping.

He'd go on to win more, too, including the British road race title in 2007, and time-trial stages at the Giro d'Italia and the Vuelta once more. And after winning stage 12 of the 2012 Tour de France – a road stage on which he outsprinted AG2R's Jean-Christophe Péraud, and which would turn out to be his last pro victory ahead of retirement in 2014 – he'd repeat what he'd said after winning his Vuelta stage in 2006: that it really was possible to win clean.

David Millar was already one of cycling's personalities, but through his actions in the fight against doping later in his career, he also showed real character. (EB)