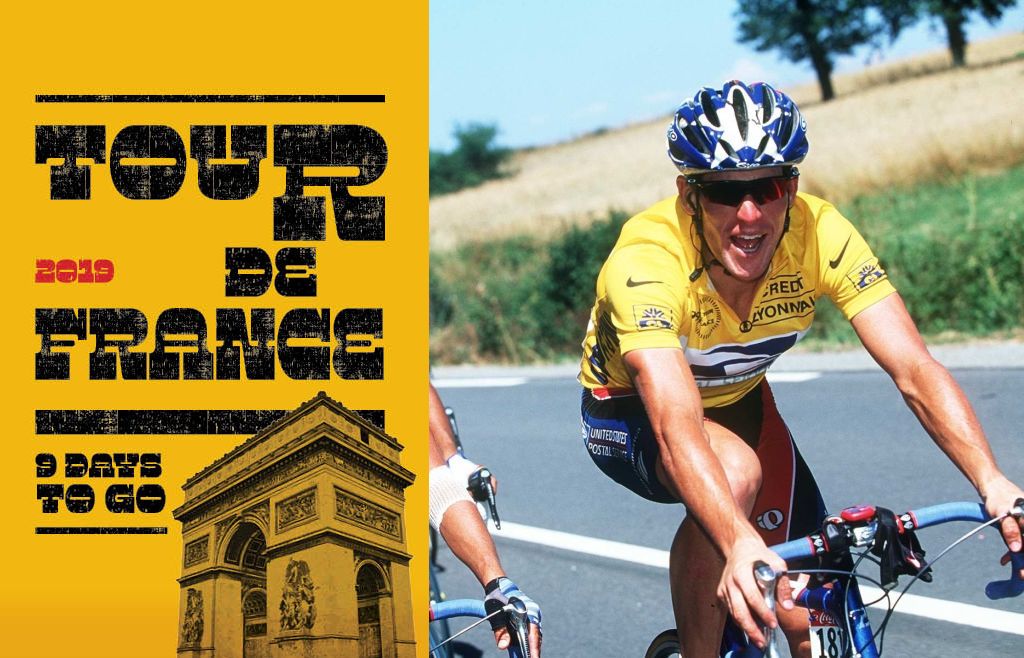

1999 Tour de France: The farce of renewal

Looking back 20 years to the post-Festina Tour and the falsest of dawns

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Twenty years ago, the Tour de France was vaunted by the organisers as 'The Tour of Renewal'. It was 12 months after the Festina doping affair had almost brought the race to its knees, but hopes for a new dawn were made a mockery of as failed doping tests were covered up, clean riders were vilified, and speeds were faster than ever.

In the latest feature in Cyclingnews' annual countdown to the Tour de France, Jean-François Quénet, who covered the 1999 Tour with a sceptical view of Lance Armstrong, recalls a farcical three weeks.

It started with a dispute between ASO and the UCI. 17 days prior to the start in Le Puy-du-Fou in the Vendée province, race director Jean-Marie Leblanc and ASO president Jean-Claude Killy rejected the participation of the TVM team and a few individuals like Richard Virenque and Manolo Saiz, who were considered troublemakers and harmful to the image of the Tour de France.

However, three days before the prologue, the UCI instructed the organisers to reinstate Virenque and Saiz, who had made an appeal because the rule of a 30-day limit to enter participants hadn’t been respected by ASO. At the time, wildcards were given after the Critérium du Dauphiné and that rule was hardly respected by any organizers or teams but Leblanc declared himself “legalist” and didn’t argue. His morning run together with UCI president Hein Verbruggen was widely commented upon.

Love him or hate him - there wasn't much room for moderation - Virenque was at the centre of attention but there was no previous winner of the Tour de France on the start list; Bjarne Riis and Jan Ullrich were injured and Marco Pantani was in no mood to ride after being expelled from the Giro d'Italia for failing a haematocrit test. There was no five-star favourite but on the morning of the race, L’Équipe rated Lance Armstrong at four stars along with Abraham Olaño. The American was surely the hot favourite for the prologue, having won short time trials at Circuit de la Sarthe and the Dauphiné, it was just not sure how well he’d go in the mountains.

As Alex Zülle, riding for Banesto, crashed on the Passage du Gois – the road from the Noirmoutier island that floods with the tide – Saiz urged his ONCE team to pull as an act of revenge one year after the Swiss rider [a member of the Festina team in 1998] told the French police that doping was also a common practice at ONCE, his former team.

In their introduction of the ‘Tour of Renewal’, race organiser ASO had declared they’d be happy with the race being 3km/h slower than 1998. However, after one week, the average speed was faster than ever: 43.737km/h. Armstrong’s performance against the clock on the 56.5km course around Metz was a shock: 49.416km/h. It was superior to Miguel Indurain’s similar domination seven years before in the nearby Luxemburg (49.028km/h).

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

During the first rest day’s press conference, the Texan was already facing a barrage of questions.

“I assure you that I don’t dope,” he firmly stated in Le Grand Bornand.

Armstrong grew frustrated at the scepticism from the media

Monsieur Propre

Once through the Alps, where Armstrong also outclassed his rivals, the Tour was back to its old traditions. Just one year and one week since Festina’s soigneur Willy Voet had been arrested at the Franco-Belgian border, sparking the Festina affair, Leblanc was giving out medals to other Belgian soigneurs for reaching 20 participations in the Tour. Virenque was back in the polka dot jersey; it was business as usual.

Banners read: 'Armstrong at home, Bassons in the peloton' and 'For Bassons, against doping'

There was, however, a glitch. A former Festina rider refused to subscribe to the so-called omertà, the old-school law of silence respected through the ages by the cycling community.

During questioning by police in the heat of the previous year's scandal, Festina riders Christophe Moreau and Armin Meier had both opened up about the prevalence of doping but had both highlighted an exception to the rule. Christophe Bassons, they insisted, did not dope.

Riding the 1999 Tour de France for La Française des Jeux [now Groupama-FDJ], Bassons had a column in the daily newspaper Le Parisien. He didn’t say much, even if, the day after Armstrong’s stage win in Metz, he ironically questioned: “But what was the EPO for?” However, every day his column was introduced with: 'Useful precision: Bassons rides on clear water, which means doping free'.

That did not go down well with the rest of the peloton. At the beginning of stage 10, following his solo win in Sestrières, Armstrong tried to bully Bassons in the peloton, and realised the Frenchman could understand English. He told him he should shut up, that there was uncertainty surrounding his team’s sponsor, and he’d better think of his own interests. Bassons replied that he was rather thinking of the interest of the next generation of cyclists and that he could just as well take on another job. An increasingly irritated Armstrong advised him to quit cycling on the spot.

As Armstrong’s performances started to attract suspicion, media interest in Bassons, who went on to become known as 'Monsieur Propre' (Mr Clean) picked up. Jealousy seemingly grew not just in the peloton but inside his team, too. He was criticised by his teammate Stéphane Heulot and even his sport director Marc Madiot, the current Groupama-FDJ manager, who told him to rest instead of giving lengthy interviews.

And so Bassons suddenly left the Tour on the morning of stage 12, sending reporters scrambling across France, looking for him in various airports.

Corticoids and tear gas

General media interest in the race, however, decreased during the transition stages between the Alps and the Pyrenees, and Armstrong was trying to keep a low profile. "I’ve stopped attacking because every time I do it, the press suspects me of doping," he lamented.

There was more scandal around the corner. Stage 11 winner Ludo Dierckxsens didn’t fail the new doping test for corticoids but messed up when declaring to the doping control officer which medicines he'd taken for a supposed knee injury, accidentally naming a banned corticoid. His Lampre team were already on thin ice after television reporters had found dubious medical waste in their rubbish bins during the Tour de Suisse. And so when they themselves kicked Dierckxsens out of the Tour for self-medication, there was no escaping the suspicion that the Belgian champion was a fall-guy, sacrificed on the altar as they scrambled to scrub clean their image.

There was to be a failed doping test for corticoids, as it emerged that triamcinolone had been detected in the urine of none other than Lance Armstrong, in a sample taken after stage 1. The American, however, remained in the race. He defended himself, arguing that he’d used a skin cream to treat saddle sores, and presented the UCI with a back-dated medical prescription for the substance. The UCI, in complete breach of its anti-doping rules, signed it off and the race went on.

In the Pyrenees, the atmosphere of the race was lousy. Cofidis' Christophe Rinero, fourth overall and King of the Mountains in the 1998 Tour, got himself into an argument with spectator, who yelled at him: "It was easier with EPO!" This time, Rinero would go on to finish 79th. During stage 19 to Bordeaux, tear gas was sprayed from the crowd onto the riders, and many had to stop to wash their burning eyes.

Long live EPO reads a sarcastic banner in the Pyrenees

Armstrong won the penultimate-day time trial at Futuroscope, and did so at an even higher speed than in Metz, which was before all the mountain stages. His average speed of 50.085km/h was followed 24 hours later in Paris by a new record speed for the Tour as a whole: 40.273km/h.

Those records, of course, have not stood the test of time.

Twenty years ago, even the observers who didn’t believe that Armstrong was riding clean gave him credit for the message of hopes he delivered as a cancer survivor. Since then, the evidence of the fraud has gradually emerged and resulted in his titles being nullified.

That took more than 10 years, and the UCI took a similar amount of time to start piecing back together its credibility. Seven years after the Festina Affair, cycling was rocked by the Operación Puerto doping scandal. And even today Operación Aderlass is uncovering new secrets.

Perhaps the Tour de France organisers were slightly hasty with their declarations of renewal.