1958: The year an outsider won in Roubaix

Léon van Daele. Who? Well, I can tell you're underwhelmed. Search the records and you'll find that...

Tales from the peloton, April 11, 2008

The greatest names in cycling have won Paris-Roubaix, and those who haven't really wish that they had. Francesco Moser, Eddy Merckx, Sean Kelly, Andreï Tchmil, Rik van Looy, Fausto Coppi... they've all won it. So, a century ago, did Maurice Garin, the first winner of the Tour de France. And then 50 years ago, Paris-Roubaix was won by... Léon van Daele. Cyclingnews' Les Woodland recounts his tale.

Léon van Daele. Who? Well, I can tell you're underwhelmed.

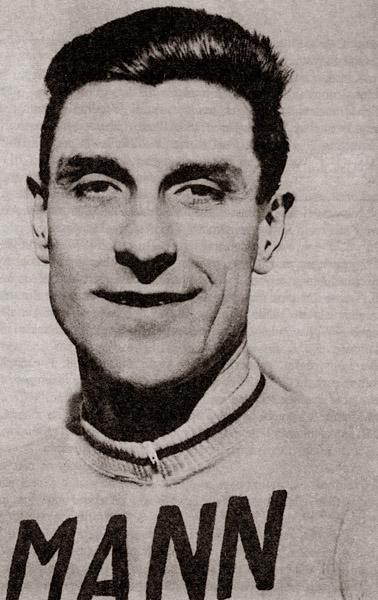

Search the records and you'll find that this man with a generous chin and heavily-hooded eyes once won Ghent-Wevelgem, and he twice won Kuurne-Brussels-Kuurne. But it's hardly the stuff to set your pulse racing, is it? So, spool back 50 years and I'll give you hope. Because, without being rude, if a complete outsider can win Paris-Roubaix then so one day may you.

Léon van Daele was 25, a professional for five years. Until the previous year he'd been good for little more than a handful of criterium wins a season. Then, in 1957, things looked up and he won Paris-Brussels and came seventh in the world championship. If you look closely enough, he also came third in that year's Paris-Roubaix, but Fred De Bruyne had won alone and van Daele came second to Rik van Steenbergen in the bunch of 20 that came in a minute and a quarter later. Van Daele's mother noticed and you can just make him out in pictures of the podium, but the lap of honour was ridden by De Bruyne and van Steenbergen and nobody cared that the third man wasn't there.

Then came 1958, that day 50 years ago when the sun shone and a cold wind blew and the riders finished with nothing more on their jerseys than sweat stains and a coating of dust. It had all looked so good. A little group was clear and in it were Jacques Anquetil, who won the Tour de France five times, Shay Elliott, the first Irishman to wear the yellow jersey, André Darrigade, who made a habit of winning the Tour's first stage, and a couple of others.

A puncture put Darrigade out of the running and the French lost interest in their spring classic when the bunch swallowed up the break and ended Anquetil's hopes. Anquetil would never have matched Elliott or Darrigade in a sprint but Elliott was open to negotiation and no doubt the two discussed the price of a lead-out against Darrigade.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

There was no TV coverage to the stadium in those days and so all the crowd knew was that the remains of the field were back together and that, while doubtless they were going to be denied a home win, they'd have the unusual sight of a big group coming through the tunnel and sprinting for the line. That at least would justify their patience.

The last loudspeaker announcement they heard was news that the speaker had picked up from race radio. And that was that the peloton was together. So surprise was complete when they got not a bunched hoard but the chubby Irishman Elliott in his red, white and blue St-Raphaël jersey and the second unknown in our story: a Belgian called Roger Verplaetse.

Verplaetse hadn't even done what van Daele had done. Second in the national championship and enough criterium wins to keep the bread on the table, that's all. A man like that wasn't going to last against a sprinter like Elliott. But then again, Elliott didn't look like lasting against the barbarians milling on behind him. Sure enough, he and the dream-groggy Verplaetse died their death as the bell rang for the last tour of the shallow, broad track in the Roubaix suburbs.

Roubaix is just across the border from Belgium. Like its neighbour, it is in Flanders. And out of Belgian Flanders every year come thousands of Belgian bike fans keen to see one of their own win. They thought it would be Rik van Looy. He'd won Milan-Sanremo and on a day when there was neither rain nor mud to laugh at his chances, nobody would be faster. The Belgians spilled their fries and leaned forward to see him triumph.

What they saw instead was a rider that most of them were pushed to name. Even the commentator faltered. A giant guy in a red and white jersey. A Faema jersey. A Belgian! Yes, a Belgian!

But who?

Van Daele did what any opportunist should do when he doesn't stand a chance. He gets his move in first and he gambles the big names will hesitate because they fear each other rather than him. He jumped with 300 metres to go, out of the saddle and then down on the drops at the bottom of the track like a pursuiter.

Chaos behind, of course. Rik van Looy wasn't going to take it lightly because van Daele was in his team. In van Looy's teams there was just one tactic, and that was to make van Looy win. He went after van Daele and Rik van Steenbergen went after van Looy. For many years the two could barely bring each other to shake hands. The bunch was at another five lengths.

Van Steenbergen never caught van Looy and van Looy not only didn't catch van Daele but he didn't even catch a little Spaniard, Miguel Poblet.

You don't need to ask how van Daele thought about his win. Just think how you'd think about it if you'd barely won a race before then.

"I attacked in the back straight and nobody could get by me," he said as he knocked back the obligatory bottle of water handed to him by the Perrier man. "I knew six hundred metres from the finish that I could win, even with van Steenbergen, van Looy, Poblet and De Bruyne there."

It wasn't a good day for the stars. Van Looy presented his excuses, van Steenbergen counted his money, and Jacques Anquetil promised that it would be a long, long time before he bothered much with a classic again.

And van Daele? Well, he stuck around. He came third in Milan-Sanremo next spring and he won Ghent-Wevelgem. But in the end he was just what he always was, a talented journeyman with a good sprint that never again won him anything as grand as Paris-Roubaix. He rode his last season in 1964 and then settled back to tell anybody who cared to listen how he had once won the toughest classic in the world.

He died at the end of April, 2000.