A Cuban Odyssey

Henri Charrière, called Papillon, for the butterfly tattoo on his chest, was convicted in Paris in...

Part 1 - 'Make pain your friend'

Henri Charrière, called Papillon, for the butterfly tattoo on his chest, was convicted in Paris in 1931 for a murder he did not commit. When he was sentenced to life imprisonment in the penal colony of French Guyana, one thought obsessed him: escape. After planning and executing a series of treacherous yet failed attempts over many years, Papillon was eventually sent to the notorious prison, Devil's Island, a place from which no one had ever escaped - that was, until Papillon. His escape, described in breathless detail, was one of the most incredible tests of human cunning, will, and endurance.

From the movie Papillon (1973) - Camp Commandant: "Make the best of what we offer you, and you will suffer less than you deserve."

After this trip to my beloved Cuba for the 30th Vuelta Ciclista a Cuba, I have promised myself that I will forevermore strive to make the best whatever situation I face. I will eschew negativity, pessimism and cynicism and will harness the primordial ability that we all possess to effect positive change by focusing the power of the mind and believing in one's ability to achieve the impossible.

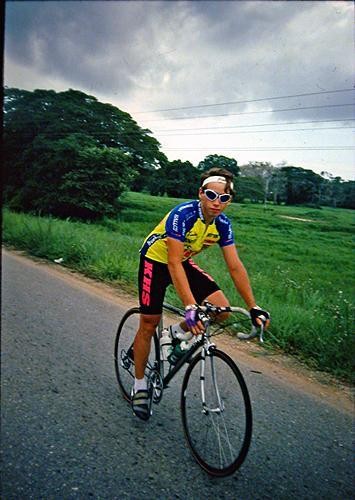

Only once before have I tapped into this internal energy to achieve results that should not have been physically possible - in 1994 during the Tour of Venezuela, which I finished (with several top-5 stage results) despite being ill with salmonella and giardia and eating less than 1000 calories per day. Though I felt sicker than I had ever been before, I was determined to finish the race - my first international competition - because I'd convinced myself that to abandon would mean that I "couldn't make it" in cycling. While maybe not the most logical conclusion, I took it day by day and made it to the finish.

My goals for this year's Vuelta a Cuba were of a similar vein, though in retrospect I did underestimate the power of the mind to overcome the limits of the body. All I wanted was: 1. To make it as far as the finish of stage six in Ciego de Avila - my wife's home province. 2. If I achieved #1, to then finish the entire Tour and cross the line in Havana. 3. If it looked like #2 was within reach, to then win an intermediate sprint.

However, the first part of my trip to Cuba left me feeling less capable than ever of reaching these modest aims!

It was a cool, grey, rainy Sunday afternoon in late-January when I arrived in Havana from equally cold and rainy Southern California, but I was still excited about returning to Cuba for a stab at the Vuelta and, of course, a reunion with my wife. My plan was to spend a few days with Yuliet before traveling 256km to Cienfuegos for the Vuelta a Cienfuegos, a five-day stage race that I've ridden every year since 2002 as preparation for the Tour of Cuba. Unfortunately, none of my luggage arrived with me! Ack!

This would not normally be a problem in even the most backward of third world Latin American countries, since one could reasonably expect the late luggage to be delivered that evening, or the following day. But given that I had come from Miami on a charter airline (with the expressed-written permission of the US Government), and my bags didn't arrive on the second or third flights of the day, I was embarcado. Screwed. The next flight to Havana by the charter would be on Thursday. I'd left some clothes and toiletries at my wife's house the last time I was in town, and I thankfully had several pieces of Patagonia with me in my carry-on, but otherwise I was SOL.

At this point, I didn't do a very good job of making the best that was on offer, except when it came to spending time with my wife. Each second with her was precious beyond description, though tempered by my sporting difficulties. I thought that my career was coming to an unjust end because in addition to being injured and not having been able to prepare well in the USA, I wouldn't be able to do any last-ditch physical preparation (like racing in Cienfuegos, which had always served me well) before the Tour of Cuba started. I was definitely digging myself a mental hole!

I was stressing even more than usual because only a few hours after I landed, a journalist friend recorded a radio interview with me for the following morning since I was the first foreign rider to arrive in Cuba for the Tour. And for the record, Todd Herriott is still incredibly famous on the island for having won the Vuelta in 2003, and even I am a relatively well-known foreign sports personality in Cuba, so riding a crappy Vuelta and maybe having to abandon because of poor form would have left my wife, her friends and family and all of my amigos in Cuba wondering why I couldn't pull it together and what had happened to the American juggernaut that took the Tour by storm two years ago.

I want to take a moment and try to clarify something for those of you who might be giving up valuable work time to read my diary - I understand that I will never race as a professional in the Tour de France; that I'm not nearly as talented a rider as many of my colleagues who don't have the time or the desire to write diaries; and that in a very Euro-centric sport, I'm just a guy from the USA who has spent 10 years racing smaller international races in countries with strong cycling traditions, that are nevertheless "off of the radar." However, the success that I have enjoyed in Cuba - regardless of how you rate it in comparison to the achievements of other cyclists in other parts of the world (if you rate it at all), and the fact that I married a Cuban and have competed there since 2001 means that I am a sports personality there and not just a normal Joe. I enjoy my notoriety in Cuba, I feel a responsibility to ride well there (for myself, my family, my team and my country) and the Vuelta a Cuba is one of my most important races of the year.

I'll detour around the political side of things, because it's been written about to death, but more importantly, I still have to get Yuliet to the United States and don't want to write anything that could compromise our future. Just please understand that a convergence of factors has created the surreal situation in which an American cyclist fell in love with and married a Cuban cyclist at a time when their respective countries are still locked in de facto cold war. Yet the American cyclist also fell in love with the country, its people, and its national cycling tour...so yes, the Vuelta is my personal Tour de France and I hope you can respect that.

Next Entry - The Vuelta a Cuba's chequered history

Email Joe at joe@cyclingnews.com

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!