Book extract: When Bassons met Armstrong

Ex-pros discuss doping and choices at 2013 meeting

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

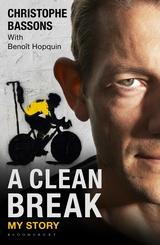

In December 2013, Christophe Bassons met Lance Armstrong in Paris. As well as touching on their brief conversation on the road to Sestrières during the 1999 Tour, the pair discussed what it was that set them on very different paths, as Bassons reveals in this extract from his autobiography, A Clean Break:

Sometimes people ask me if I’m happy with what has happened to Lance Armstrong. This question really annoys me. Why should I be happy? What has changed that would satisfy me? Lance Armstrong has good reason to see the irony in the status of scapegoat that has been conferred on him. Over the winter of 2012–13, it seems I hardly stopped speaking about this man with whom I had only talked after all for just a minute of my life, even if that minute did seem particularly long… …

Via intermediaries, I learned that the American wanted to meet me. My first impulse was to say no. I was afraid of being manipulated, trapped. Was he intending to get me involved in his complicated judicial affairs, to use our tête à tête as a way of appeasing the American courts? I am fully aware of the importance of redemption in American culture.

And then I said yes. I realised that even though his request might have been self-serving, I also needed to have this meeting. I had questions, lots of questions, to ask him. I had personal issues that I wanted to settle before moving on to other things. The conversation we had started on the descent from Sestrières had only lasted a few seconds. It needed to be completed.

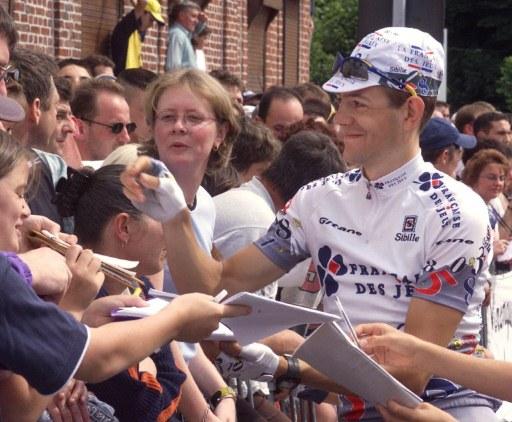

In addition, I could see a good reason for having such a meeting with regard to the prevention of doping. What could be better than showing that choices made in the short term do not always turn out to be the best in the long term? It was to be me, the little outcast within the pro peloton in the years between 1998 and 2001 against Lance Armstrong. As they say in tennis, we would be at love-all with Bassons to serve!

The meeting took place in a room at Fouquet's, a renowned restaurant on the Champs-Elysées. Lance Armstrong had finished seven Tours de France with the yellow jersey on his shoulders on this avenue. I saw him arrive with a cap pulled tight down on his head. His features were drawn. The week before, he had met his former masseur Emma O’Reilly and asked her to forgive him for dragging her name through the mud after she had called his performances into question. I also knew he had just met with Filippo Simeoni in Italy.

Lance ordered a drink and fiddled with embarrassment with the glass throughout our conversation. He immediately returned to what he had told me during the 1999 Tour. He tried to explain that he hadn’t wanted to wound me, and then stated, ‘If that was how you felt at the time, I really have to apologise. I’m sorry.’

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

‘There is no need to apologise,’ I replied. ‘At least you said what you had to say to my face.’ I explained how French riders had done as much he had in teams of my eviction from the race thanks to their hypocrisy, insults and intimidation.

He told me that he had plenty to say about cowards and hypocrites too. ‘My life today is full of this kind of personality. When you live through the kind of period that I experienced, you learn all kinds of things. You don’t only learn lessons about cycling, but about life too. You learn who your real friends are. There are people who I could have sworn were on my side. I would have trusted them 100%. I thought that they would stick with me. But, hey presto! They disappeared! At least I know who I’m dealing with. It’s great when you walk about in the yellow jersey, everyone is having a good time and wants to pat you on the back, saying: “What a great guy!” But then I discovered what people are really like. I’ve found that out for myself. Suddenly, there were far fewer people around me. But I’ll tell you this: last year’s events, which started with USADA, and all the problems that resulted from that both for me, my family and those around me, no longer have any value.’

He continued, his bitterness evident: ‘I was demonised. But the former leaders of the UCI are as evil as me.’ He added: ‘Unfortunately, cycling is not a better sport today than it was 12 months ago.’ I couldn’t agree more. I found myself taking to his defence. ‘I don’t agree with you taking the blame for whole milieu. I don’t think you’re responsible for everything that’s happened. The UCI, the federations, the organizers also have to take some of the blame. We have to put an end to this hypocrisy.’

… He told me how he had started doping when his team managers began to get impatient at his lack of performance and were talking about sending him back to Texas. ‘That was in 1994. They really had a go at me, but I said, “No, no, I’m not taking this lying down.” I told them: “Fuck you... I’m staying.” This is a cultural problem. The riders are fighters, we’re there to fight. I said: I’m carrying on. I’m not going home. I’m staying here to fight.’

I knew everything that he was talking about so well from personal experience. I had also experienced that same pressure for results. I had just made a different choice. He had drawn on his determination, his strength of character and his obstinacy to remain in the peloton come what may. I had called on these same qualities to resist. I’ve never regretted it, and that night, as I sat face to face with him, I was even prouder of what I had done, even more convinced that I had made the right choice.

To purchase A Clean Break by Christophe Bassons, click here.

Peter Cossins has written about professional cycling since 1993 and is a contributing editor to Procycling. He is the author of The Monuments: The Grit and the Glory of Cycling's Greatest One-Day Races (Bloomsbury, March 2014) and has translated Christophe Bassons' autobiography, A Clean Break (Bloomsbury, July 2014).