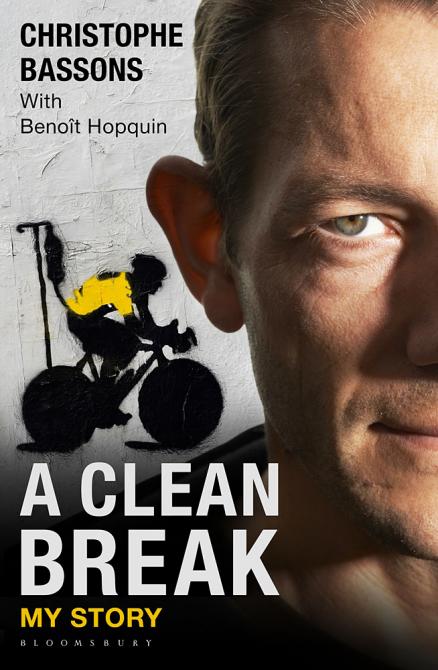

Book Extract: A Clean Break by Christophe Bassons

Retired pro chronicles his experience in doping-filled peloton

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A prodigious amateur talent, Frenchman Christophe Bassons turned pro in 1996 and joined the mighty Festina team later that season. Despite his coach's assessment that he had the same physiological attributes as five-time Tour de France winner Bernard Hinault, Bassons never made the breakthrough that was expected. In a peloton where drug-taking was generally systematic, Bassons refused to yield to persistent encouragement to dope.

In 1999, Bassons lined up in the so-called "Tour of Renewal" that followed 1998's catastrophic race. Quickly sensing that renewal was a fantasy, he became increasingly critical of his peers and professional cycling in his column in Le Parisien, provoking the ire of, amongst others, emerging Tour champion Lance Armstrong. Alienated and isolated, Bassons quit the race midway, but continued to voice his concerns. In 2000, he wrote Positif, revealing his experiences in the pro scene and his vision for a healthy future. A year later, no longer able to cope with the deception being enacted within the sport, the principled Frenchman quit racing to become a teacher.

In 2013, following Armstrong's confession, a meeting with the disgraced champion and an apparent renaissance for pro cycling, Bassons returned to Positif and decided to update it, to offer a very different perspective on professional cycling. In this extract from the book - now out in English under the title A Clean Break - Bassons explains why:

I was bit of a one-off. I didn't claim to be either better or worse than the rest. In his book, Secret Défonce. Ma vérité sur le dopage, Erwann Menthéour described me as ‘extraterrestrial'. This was how the people in this two-wheeled world viewed me. But that perspective is skewed. If one person is riding normally and another is doping, which should we think of as the Martian?

If a polling agency were to conduct a survey among the population, 95 per cent of people would say that they would refuse to poison themselves in order to win. When I became part of the pro cycling scene, 95 per cent of professional riders were doping. (In the United States, a study conducted among top athletes showed that three out of four athletes said they would be happy to die before they were 40 if it meant getting an Olympic medal.) I find this disparity between popular opinion and the attitude of sporting champions appalling. I believe top-level sport has been usurped by people who are not necessarily the most talented or the strongest, but are simply the most determined or the most oblivious to danger. Sorcerers' apprentices who pretend to be doctors are then responsible for providing these kamikaze athletes with the physical means to achieve their goals. Although life expectancy is increasing within the general population, it is continuing to fall in cycling.

It is this situation, which is suicidal for the athletes involved and for my sport in the long term, which motivated me to write a book. In 2000, when I was 26, I wrote the first version of this memoir knowing I would be condemned by the peloton. My initial comments were also my testament as a professional, as by that point my situation seemed increasingly precarious, and was perhaps even untenable. I should probably have prefaced my remarks by declaring: ‘I, Christophe Bassons, being of sound mind and judgement...'

Even though the deception carried out during the Armstrong years, when I was the pariah, has since been proven, I am returning at the age of almost 39 to this autobiography with the intention of providing a clinical examination of the cycling milieu.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

I have chosen to use the word ‘milieu' because it seems most accurate to me in many of its senses. The peloton acts as a club, a framework for life, an ambience even. In many ways, it also seems to live up to the pejorative definition of the word: a group of individuals living on the margins of the law.

Cycling still offers lessons for life, drawn from city streets and the winding roads of the countryside. Unfortunately, this education is less poetic than it once seemed. Cycling hastened my move towards maturity. It enabled me to have a clear view of my life and what I wanted to do when I was in my twenties, at an age when other youngsters are floundering. But the four years of adversity I spent in the peloton taught me so much more! I saw so many things that I feel there is a lot I can usefully share.

My story can serve as an example. When I say that, please don't take it as boastfulness. I don't mean example in the sense of self-satisfaction in one's own achievements, but in the sense of serving as a lesson or warning. I do not think I should be viewed as a model to follow, a reference point, but simply as a good example. I need to explain what doping means for cycling, how it became not only a physical imperative but also a moral obligation. I have to explain the chain of events that led me to the point where my choice was to dope or to quit. I want to describe the degree of coercion that permeated the professional world, both to the youngsters who are coming into the sport with the duty to change old habits and to the old stagers who had the good fortune to live in healthier times. I want to relate how a tender boy blessed with some talent and a real passion for cycling, to the point where he wanted to make a career of it, found himself caught up in a mechanism shaped not by the toughness of the sport, but by the men within it. I particularly want to detail the steps on the pathway that leads someone to inject himself, not in order to win, but simply to exist within this family.

I want to shed a little more light on the hypocrisy that I have experienced. This is done so that, in future, a kid whose love for the bike leads him into the peloton doesn't end up experiencing the same disappointment I did.

It is for the sake of that boy or girl that I have to speak out.

To purchase A Clean Break by Christophe Bassons, click here.

Peter Cossins has written about professional cycling since 1993 and is a contributing editor to Procycling. He is the author of The Monuments: The Grit and the Glory of Cycling's Greatest One-Day Races (Bloomsbury, March 2014) and has translated Christophe Bassons' autobiography, A Clean Break (Bloomsbury, July 2014).