Tinkov's €1 million challenge, will it happen?

Carlos Sastre and Stephen Roche share their thoughts

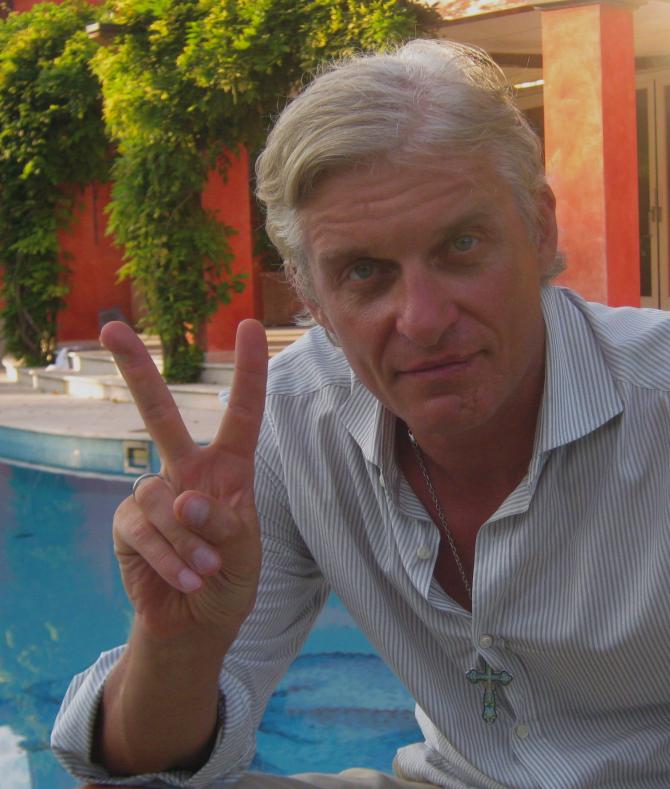

Who wouldn’t want to see the world’s best riders go head to head in the Grand Tours? In his own eccentric way, Oleg Tinkov is trying to make that happen in 2015. Tinkoff-Saxo has gone as far as calling a meeting in Paris next week – when all the teams will be in town for the announcement of the Tour de France route.

Tinkov’s €1 million offer to the top four Grand Tour riders to attempt all three has received a mixed reaction from his team’s rivals. While Movistar and Sky seem open to the idea, Vincenzo Nibali has disregarded it, saying that Tinkov would be better off using the money on a development team. The Russian businessman and his team may be serious about it, but can they make it happen?

Former Tour de France champion Carlos Sastre is one of a select few modern day riders to have done it to a high level. The Spaniard isn’t convinced that the idea will become reality. “I think that it’s not going to happen, because all of those riders are in a different team. He can control what happens in his team but not what the other riders are doing,” Sastre tells Cyclingnews.

1987 Tour de France victor Stephen Roche hasn’t ridden all three Grand Tours in a year, but is one of only two riders to win the Tour, Giro d'Italia and World Championships in a single season. The Irishman agrees with Sastre that it’s unlikely to happen in 2015, but thinks – with a lot more planning – that the idea has some merit.

“He’s (Tinkov) right that all the big tours should have all the big riders, giving those tours their just value,” Roche says to Cyclingnews. “I think that it’s a good initiative, but it needs more thought.”

The money

More than anything, it is Tinkov’s offer of €1 million that has got tongues wagging over the wager. The number sounds like a lot, but when you stop and consider it the amount seems quite miserly. The million would be divided equally between the four riders, meaning that each would take home €250,000 – less than the €450,000 on offer for winning the Tour de France alone. If you start dividing that down between the teammates, is the risk really worth the reward?

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“Those riders they make a lot of money, so €250,000 more for all of those riders means nothing. It’s a lot of money for a normal rider, but not for them,” said Sastre.

Roche thinks that the stakes should be higher to make the challenge truly attractive. “I don’t think €1 million is enough,” he says. “I think everyone should bring one million Euros into the pot and make it really interesting and worthwhile for the rider.

“Then they’re asking them to do all the three major tours, which, in turn, might leave them dead for the following season. It’s a risk.”

Is it possible?

The physical strain on the riders is probably the biggest consideration for the teams. Is it possible for four riders to compete at such a high level over nine weeks of racing, and what are the inherent challenges of completing all three Grand Tours in a season?

Only 32 riders have ever done it and only one rider has ever won one in the process. Italy’s Gastone Nencini completed the trio of major tours in 1957, winning the Giro d’Italia, taking two stages and the mountains classification at the Tour de France and finished ninth overall in the Vuelta a España.

The number of riders tackling the challenge has drastically dropped since the mid 1990s, when the Vuelta moved from April to September. Only 8 riders have completed it in the last decade. Over the last three seasons, Adam Hansen has equalled the record run of 10 consecutive Grand Tours, but has not had to consider the general classification during that time.

Sastre’s first run in 2006 – his second came in 2010 - is probably the closest comparison we have, where he claimed fourth at the Tour and the Vuelta. However, he rode the Giro d’Italia in support of Ivan Basso, thus saving some his reserves for his two bigger goals. Sastre isn’t sure that competing for the general classification in all three is possible with their current calendar.

“They are not doing only the three-week tours, they are doing a lot of races during the season. If you want to be good in every one it isn’t possible. I think many things need to happen before we see something like that,” he explains.

The 39-year-old suggests bringing the number of days down from 21 to 16 to make it a more realistic prospect. Roche disagrees however, and believes that the Grand Tours should be left as they are. “It’s like having Paris-Roubaix and taking out half of the cobblestones,” Roche tells Cyclingnews. ”You have to make the races extreme. I think that the Grand Tours are extreme. They are generally quite balanced with the parcours but the length of it is always three weeks.”

He does concede that something needs to be done to avoid riders looking for ‘shortcuts.’ “We don’t want the riders to revert to doping. So the riders don’t have thoughts about doping we have to give them a nice programme.”

The challenges

Taking on the task of three Grand Tours in a year isn’t just about the 63 days of intense racing. It brings with it the multitude of training camps and recons that go hand in hand with a serious GC attempt. “Between training camps and tours you’d be on the road all the time,” says Roche. “It is extremely tiring and being away from home could cause a lot of problems.”

This season, Tom Veelers (Giant-Shimano) completed the most number of race days, with a total of 101. At 70 race days, Tour de France champion Vincenzo Nibali completed more than any of his rivals. Alberto Contador was close behind with 65, Nairo Quintana rode 60, while Chris Froome did only 52.

They may have been affected by injuries, but few Grand Tour contenders will ride much more than that. “Of course it was very difficult, because it is three weeks where you try to be in the best shape and if you try to focus on the GC it isn’t easy,” Sastre says of his attempt in 2006. “In the last race, perhaps you have the motivation but you are missing some energy.”

Sastre believes that the biggest obstacle for the riders is not the physical aspect, however, but the mental fortitude required. “The head is the energy system of our bodies. If the head is focussed and happy, and it wants to do it then you can do it. If the head is not ready then you have a problem,” he explains.

“When you are not feeling focussed or strong, you have some kind of weakness, then luck will not be with you. Maybe you try to look for it, but the luck is not there.”

The other contenders

Tinkov has only included four riders in his offer, but there are a number of teams with Grand Tour contenders that could come and spoil the party. Riders such as Rigoberto Urán (Omega Pharma-QuickStep), Jean Christophe Péraud (AG2R La Mondiale) and Thibaut Pinot (FDJ.fr), among others, haven’t been considered. The likes of Movistar and Astana also have a second GC rider who could make the most of their tired rivals towards the end of the season.

Roche thinks that, if the challenge were to go ahead, it could back fire on the top riders. “If I’m Mr (Vincent) Lavenu or Mr (Patrick) Lefevere from QuickStep, I’m going to tell my riders that these boys are going to get a hammering in the Giro and then ride the Tour,” he says. “If we start 110% at the Tour and we send the B team to the Giro and we can win the Tour then that million Euros we can get back in advertising easy.”

Will it happen?

The resounding belief is that it won’t happen in 2015. There are many more factors that just sticking the three races on the riders programmes and be done with it. Will other races be affected by the riders’ absence? Should the races be reduced in length? Is one million enough? Is this a one-off thing? If not, who gets selected? Is it feasible to run it every year?

There it a lot for the teams and riders to consider before it can even go ahead. The biggest questions of all is are the riders willing to make the huge sacrifices necessary to take it on and do they want to do it?

One question that doesn’t need asking is do the fans want to see it happen? That must surely be a resounding yes.

Born in Ireland to a cycling family and later moved to the Isle of Man, so there was no surprise when I got into the sport. Studied sports journalism at university before going on to do a Masters in sports broadcast. After university I spent three months interning at Eurosport, where I covered the Tour de France. In 2012 I started at Procycling Magazine, before becoming the deputy editor of Procycling Week. I then joined Cyclingnews, in December 2013.