The Stelvio: The sacred mountain of the Giro d'Italia

Extract from Daniel Friebe's book Mountain High

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

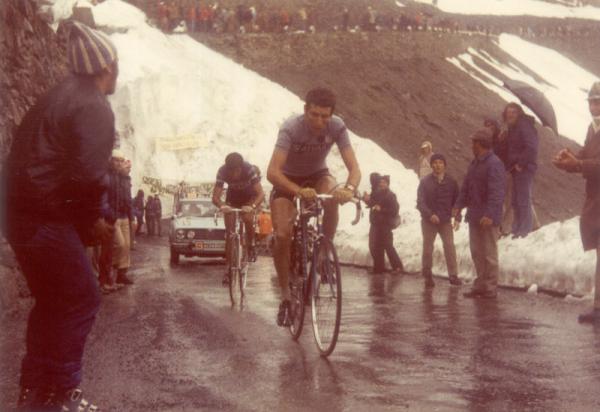

The Giro’s ascent of the Stelvio may not only decide the race but also represent a pilgrimage to the ‘sacred mountain’ of Italy’s national tour. In this extract from his bestselling book Mountain High (Quercus), Daniel Friebe unravels the mystique of possibly Europe’s greatest mountain road.

If Fausto Coppi thought he ‘was going to die’ while climbing the Passo dello Stelvio during the 1953 Giro d’Italia, the man the Italians dubbed ‘campionissimo’ could have perished in worse places. Robbed of its status as Europe’s highest road pass by the Col d’Iseran in 1937, the Stelvio nonetheless remained and remains today arguably the purest, most exhilarating, most spellbinding mountain playground accessible to cyclists. Not that either of the eastern (from Prato allo Stelvio) or western (from Bormio) ascents offers much in the way of recreation; one Italian rider who scaled the Stelvio in the 2005 Giro, Marco Pinotti, called it ‘an ascetic experience’ – an act of self-denial and quasi-religious devotion.

Long before cycling and the Giro, the Stelvio was one of Italy’s great national landmarks. Not that modern-day Italy was even a recognised entity when, by virtue of the 1815 Treaty of Vienna, the Habsburg Empire took control of Lombardy and immediately began hatching plans to connect the region to the neighbouring Tyrol. The answer would be a road crossing from Valtellina in Lombardy to the Val Ventoso, and the man to bring it to fruition was a renowned architect from Brescia, Carlo Donegani. Donegani spent a year plotting his 49-kilometre masterpiece, and it took 2,500 hardy souls five years to complete. The Stelvio was officially opened in 1825, with a delighted Emperor Ferdinand the guest of honour, but the plaudits all for Donegani. Twelve years later, Ferdinand would award him two titles – Knight of the Austrian Empire and the ‘Nobleman of the Stelvio’. Donegani died in 1845 due to heart problems reportedly aggravated by his grueling work in the Alps.

His legacy was of the very highest order, not only literally. Over a century later, that seasoned connoisseur of mountain passes [and author of The Great Motor Highways of the Alps] Hugh Merrick’s musings about the Stelvio were drenched in superlatives: ‘Most of the great passes have their individual and varied glories, of engineering skill and scenic beauty. For me the Stelvio has everything any of them has, and more than all of them put together.’

Trafoi nestles high up the eastern (some call it northern) face of the pass, the more famous and photogenic of the two ascents. From Prato allo Stelvio at the bottom to the summit, the road coils through 48 hairpin bends, 27 more than Alpe d’Huez, maintaining a relatively steady gradient of between seven and nine per cent after a gentler approach to Gomagoi. From here, two works of art, Donegani’s and nature’s, do-si-do all the way to the top, 20 kilometres away.

It is also on this side of the Stelvio that some of the Giro d’Italia’s most famous chapters have been written. In 1953, the Giro attacked the pass for the first time, thus pitting its greatest athlete, Fausto Coppi, against his homeland’s most magnificent mountain. Wearing the pink jersey of the race leader, Hugo Koblet buckled when the campionissimo attacked 11 kilometres from the summit. Not even the Swiss’s superb descending could prevent Coppi from winning the stage and, effectively, the Giro. A similar, virtuoso performance on the Stelvio saw Charly Gaul, the ‘Angel of the Mountains’, triumph in Bormio in 1961. On that occasion, however, it wasn’t enough to overhaul Arnaldo Pambianco and bring Gaul overall victory in Milan the next day

The 1956 and 1972 Giros took on the Stelvio from Bormio in the west [as the 2012 Giro will on Saturday] – an ascent La Gazzetta dello Sport called ‘a serpent of asphalt, five tunnels, 21.9 kilometres and 1,560 metres of climbing’. Aurelio del Rio and José Manuel Fuente were, respectively, the first and second to the summit, snake charmers for a day. On the eve of the 1972 race, Fuente had vowed to put Eddy Merckx out of the time limit on the Stelvio. For Fuente, no such luck: the Cannibal finished just over two minutes behind him and held on comfortably for overall victory.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Weeks earlier, Bernaudeau’s brother had drowned in a canoeing accident. Partly for this reason, the Stelvio held a special poignancy for Bernaudeau, so much so that in retirement the Frenchman would open a restaurant in La Chataigneraie in the west of France and call it Le Stelvio.

Four years later, history looked sure to repeat itself, with another Frenchman, the late Laurent Fignon, poised to kill off his Italian rival Francesco Moser on the slopes of the Stelvio. Alas, to Fignon’s everlasting disgust, race organizer Vincenzo Torriani scrubbed the Stelvio from stage 18, citing snow at the summit – snow that was curiously invisible in television pictures filmed from a helicopter. By far the superior climber, Fignon moped. Predictably, he then relinquished his pink jersey to Moser in a time trial into Verona on the final day of the Giro.

The Stelvio’s inclusion on the Giro route is, then, fraught with risk. In 1988, snow again forced its cancellation, this time legitimately. Fourteen years had therefore elapsed between Hinault’s escape to victory in 1980 and la Corsa Rosa’s next visit in 1994. That day, Francesco Vona crested first to claim the Cima Coppi prize, awarded to the first man over the highest peak in the Giro. Both Vona and, for once, the Stelvio, however, were overshadowed by the young Marco Pantani’s stage-winning exploits on the Mortirolo.

One of the unsung survivors that day was former Motorola pro Brian Smith. Smith told Rouleur magazine in 2007 that he remembered the long crawl up from Prato allo Stelvio well – and the dive-bomb into Bormio even better.

Daniel Friebe is on Twitter @friebos