Remembering Félix Lévitan

Félix Lévitan was the man who brought commerce to the Tour de France…only to be fired for trying to...

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tales from the peloton, February 21, 2007

On Sunday, February 18, 2007, former Tour de France organiser Félix Lévitan passed away at the age of 95. Cyclingnews' Les Woodland reccounts the life of the journalist turned race organiser who brought the Tour de France to the commercial world.

Félix Lévitan was the man who brought commerce to the Tour de France…only to be fired for trying to bring it elsewhere.

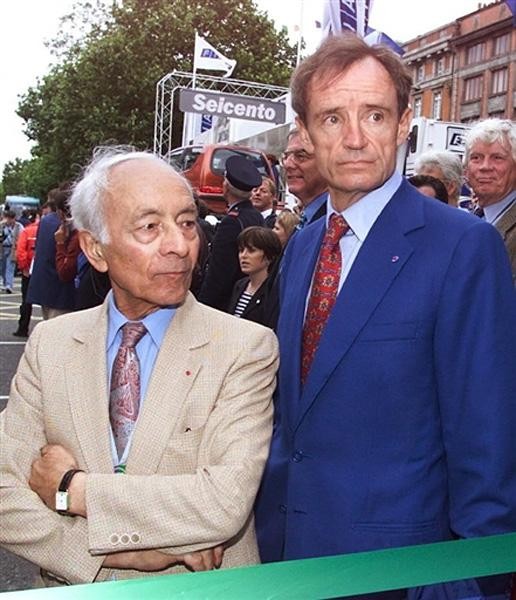

He was a short, sunken-cheeked Parisian and with Jacques Goddet he brought the Tour de France out of the heroic era of the inter-war years and prepared it for the festival of commerce it is now. The world of cycling owes a lot to both.

No two men could have been more different than Goddet and Lévitan. The first was tall, gentlemanly, spoke fluent English (though rarely did) and revelled in the glory - the thundering drums of the Tour. He wrote prose that sung to the calling of trumpets and clash of cymbals.

Lévitan was a little street-fighter, a wringer of money from sponsors, a man who saw it as his right to overrule judges and commissaires if they made a decision that didn't fit the commercial purposes he had set, and whose command of English was such that in his British car he had to stick French translations for words such as choke, windscreen wipers and heater.

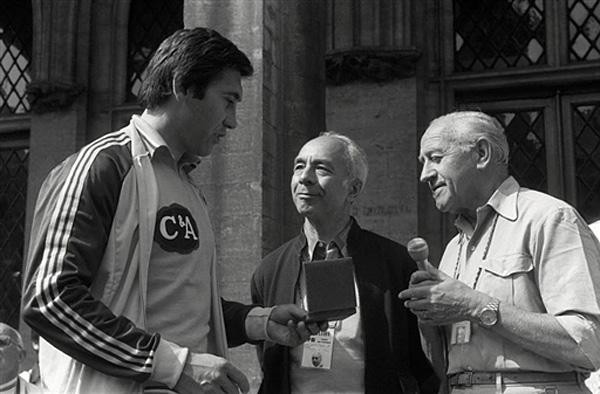

Lévitan loved cycling but in a different way from Goddet. Goddet had inherited an entire newspaper from Henri Desgrange but Lévitan fought line by line to have his reports printed. He began writing when he was 17 after hanging about at the Vélodrome d'Hiver and picking up stories from the stars.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

There is still a memory of those days in the Tour because when Lévitan had to choose a jersey for the mountain leader, he chose the polkadot design that had appealed to him at the Vel' d'Hiv'.

Lévitan wrote for Le Parisien Libéré, which was owned by a haughty press baron called Emilion Amaury. Amaury was so disliked by other papers' journalists that when he died after falling from his horse on his estate at Compiègne, the newspaper Libération ran the headline: "Riding accident: horse is safe."

Amaury had impeccable wartime connections with the Resistance. Goddet, whose own wartime record is less certain, gained the right to run the Tour de France and the new sports paper L'Équipe, only because he had Amaury's support.

L'Équipe never had the success that its predecessor, L'Auto, had enjoyed and Goddet was pleased when Amaury offered to take it into his company. When that happened in 1962 Goddet didn't have to leave but Lévitan had to become joint organiser of the Tour.

While Goddet and Lévitan never bickered in public, few people claimed they got on as any more than work colleagues. They divided the Tour between them, Goddet choosing to lookafter the sporting side, Lévitan bringing in the sponsorship.

It was Lévitan who pressed hardest to abandon national teams. Typically, Goddet wanted to keep the romance and debated with Lévitan in print. But, again typically, Goddet had to concede that so far as money was concerned, Lévitan was right.

Where Lévitan went wrong was in not thinking big enough. Rather than big sponsors spending big money, he did what the rest of the sport did and sold his race in penny bundles. The more the race declined in the 1970s, to the point where it almost had to beg teams to ride, the less Lévitan could sell anything for a decent price. There were so many sponsors that podium presentations were still going on after much of the crowd had gone home. The communist daily L'Humanité sneered there would soon be a sponsor for the rider with the prettiest smile.

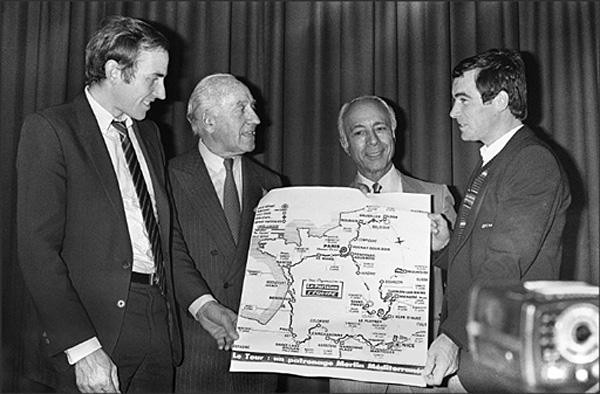

The Tour became such a mishmash that there were serious calls for it to be nationalised. Lévitan was so offended - and worried - that at the race presentation in 1981 he opened the books, pointed at the costs that the state would have to support, and said that far from fewer sponsors, the race needed more.

When Émilion Amaury fell off his horse and died, Lévitan's day went with him. Among those who detested Amaury was his son Philippe, and when Philippe took over he rid himself of anything that smacked of his father - that included Lévitan.

The reasons have never been clear but, in March 1987, Lévitan turned up for work and found the locks to his office had been changed. Two bailiffs stood by to supervise as he followed orders to clear his desk and never return.

Politely, it was described as a row over "cross-financing." Probably it was Lévitan chancing his arm and using Amaury's money to float a Tour of America. Lévitan had always seen America as the cash drawer he needed to save his race. That was why he was so delighted when Jonathon Boyer became the first American to take part, in 1981, that he insisted Boyer wear a stars and stripes jersey rather than his team kit. No other rider had ever been offered that chance. When Lévitan looked at Boyer he saw dollars.

That day in 1987, Lévitan left the Tour and went off for a long, long sulk by the Mediterranean. He refused to talk of the Tour - a pledge he kept until the day he died - and not until 1998 did he visit the race. Why he went in 1998 is not clear. Disinclined to say anything more explanatory, Lévitan explained only that "the organisation and I have come to respect each other".

The first thing that Jean-Marie Leblanc did was throw out all the five-cent sponsors and charge a great deal more to a few firms whose name wouldn't get hidden in the muddle. It has changed the Tour, which is now as big as Lévitan merely thought it was, but that doesn't mean Lévitan's work should be dismissed.

Without him, there probably wouldn't have been a Tour de France for Leblanc to take over.