Procycling's top 10 moments from 200 issues

From Wiggins Tour de France win to Pantani's last Giro

For all the unprecedented scandal and controversy that has tortured cycling and its fans since 1999, we have also been treated to some spectacular sporting drama. Here, Procycling's writers select and relive 10 of their favourite moments from the first 200 issues of the magazine. This is why.

Writers: Ellis Bacon, Peter Cossins, Sam Dansie, Daniel Friebe, Jamie Wilkins

Photography: Tim De Waele

Wiggins wins the Tour de France

Tour de France, stage 19, 21 July 2012

After an inauspicious start with Sky in 2010, when Wiggins now admits that he just didn’t do the work, and a broken collarbone when looking astonishingly fit and lean (earning the temporary nickname 'Twiggo') at the 2011 race, Wiggins returned to the Tour in 2012 carrying a little more weight and a lot more power, fine-tuned by Sky’s coaches for the TT-heavy route. Having already blazed to wins at Paris-Nice, the Tour de Romandie and the Critérium du Dauphiné in the run-up, he had the pressure of being the outright favourite but he and Sky bore it gladly. They rode at the front on the flat stages to keep out of trouble and set a consistently fierce pace in the mountains until the rest had simply fallen away.

The yellow jersey arrived earlier than expected, on stage 7, so the 41km TT two days later instead served to swell his lead. His only trouble in the mountains was a brief but much discussed attack by team-mate Chris Froome so on the penultimate day’s 53km TT Wiggins was free to stamp his authority, duly winning the stage and securing a historic victory.

When Olympic gold followed 10 days later, his status as national treasure was made official. It’s not because he’s readapting his physique for the track that we no longer call him Twiggo. Since this watershed victory, we call him Sir. JW

Andy Schleck wins with guile and bravery

Tour de France, stage 18, 21 July 2011

This was truly a day of grace. Andy Schleck and the Leopard Trek team were often criticised for poor, timid strategy. Yet on stage 18 of the 2011 Tour de France they delivered a spectacular display of strength and tactics.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Schleck began the stage over a minute down on his brother Fränk and Cadel Evans. With his GC hopes fading, he promised to attack. But instead of producing a predictable dig three kilometres from the summit of the final climb, Schleck launched himself clear of the group of favourites on the Col d’Izoard, the second of the day’s three peaks and 62km from the finish. Barely believing what they were seeing, none of his rivals followed.

Now Leopard’s plan kicked in. Two riders, Joost Posthuma and Maxime Monfort, had joined the day’s break. First Posthuma pulled for Schleck on the Izoard and then Monfort waited at the summit to guide him down the descent. With exceptional bravery, Schleck, himself a giftless descender, committed fully and followed the scything Monfort exactly. On the Col du Galibier he caught and passed the remains of the original break, winning alone by two minutes and putting himself nearly a minute clear of Evans. A masterstroke.

The success was fleeting. Normal service was resumed the next day when the Schleck brothers failed to mount an attack on Evans on l’Alpe d’Huez, apparently unwilling to risk a podium for both in order that one might win. For fans of Andy Schleck his greatness on the road to the Galibier had an extra frustration: he had proven he had it in him, so why did his tactics and descending hold him back so often?

“No battle plan survives contact with the enemy,” said the German military strategist Helmuth Von Moltke the Elder. If he’d seen his race, he may have revised his opinion. JW

Haussler loses to Cavendish by a tyre-width

Milano-San Remo, 21 March 2009

Heinrich Haussler was one of Procycling’s ‘Fab Four’ in 2006. It certainly wasn’t a bad season to have followed Haussler: he won two stages at both the Vuelta a Murcia and the Circuit Franco-Belge. But 2009 was truly the big year for the German-Australian, starting with an impressive – if heartbreaking – result at Milano-San Remo in March.

With a group of around 40 riders still together going into the final 500 metres, it was Haussler who found the strength to surge away from the rest, though he claimed he was trying to lead out teammate Thor Hushovd as per the team’s plan. Haussler looked to have the race sewn up, only for Mark Cavendish to bridge what looked like an impossible gap and pip Haussler by what was said to be a mere centimetre.

Cavendish had already proved what he could do at the Tour de France, having won four stages in 2008. Now here he was showing everyone – bar Haussler – a clean pair of heels at one of the biggest one-day races.

Later that same season, at the Tour, where Cavendish added another six stage wins to his tally, there was recompense for Haussler when he took a lone win on stage 13 into Colmar, in the Alsace region, crossing the line in tears.

But while Cavendish’s star continued to rise, Haussler’s career became one of ups and downs, often hampered by illness and injury. He may not have managed to reach the dizzy heights of that 2009 season again yet, and was cruelly thwarted into second place four stages in a row by Peter Sagan at the 2012 Tour of California, but don’t bet against the 30-year-old scoring that huge victory before his career his over. Watch this space. EB

Cancellara breezes past Boonen

Paris-Roubaix, 11 April 2010

Already the convincing winner of Harelbeke and Flanders, Fabian Cancellara went into 'the Queen of the Classics' with the white cross on his Swiss champion’s jersey, asserting his status as the man to watch. After a moving minute’s silence in memory of two-time Roubaix winner Franco Ballerini – killed in a rallying accident two months previously – the favourites were content to eye each other until 70 kilometres from home, when Tom Boonen launched a series of sorties designed to test out his rivals.

Cancellara was quick to jump on any move by the Belgian and never appeared to struggle while doing so. But the Swiss rider held himself back until audaciously taking advantage of an unexpected opportunity. Riding on the road between cobbled sections 10 and 11, Boonen was chewing on an energy bar when a quartet of riders surged off from the front of the group containing all the main favourites. Cancellara swished up to them nonchalantly, then pressed a touch harder on his pedals and was gone.

The coverage on Flemish TV captured the moment perfectly, the commentator suddenly switching to English to warn: “Balen, we have a problem. Tom, Tom, Tom, Tom...”

Boonen wasn’t alone in having a problem as Cancellara breezed past the breakaway riders. Soon the only question was by how much would Cancellara win. At one point his lead reached three minutes but was chipped back to two as he took his time celebrating his second success on Roubaix’s concrete bowl.

Another question did surface after the race. Had Cancellara, as the Italian broadcaster RaI alleged, been guilty of mechanical doping? They demonstrated the possibility of a hidden motor and the rumours persisted. “It was quite funny but it’s become a bigger story and is no longer so funny,” said Cancellara. “Believe me, my feats are the result of hard work.” What was certain is that Spartacus had never been stronger. PC

Bittersweet victory for bereft Bettini

Giro di Lombardia, 14 October 2006

In the late summer of 2005 it was looking ever more likely that the World Championships and the Giro di Lombardia were two races destined forever to elude Paolo Bettini. At the Worlds, in particular, bad luck, bad tactics and bad form had bedevilled him with the persistence of an Indian sign. At Lombardia, the problem wasn’t so much fortune or fate or even Bettini himself; the courses were simply too difficult for the best puncheur and Classics hunter of his generation.

Everything, though, was about to change. Bettini finally won Lombardia that autumn and approached the same races the next season with a renewed confidence. In Salzburg, at the 2006 Worlds, a peloton boasting several of the sport’s best sprinters stampeded into the final corners, where Bettini appeared like a rabbit from a hat on Erik Zabel’s wheel in the home straight. To everyone’s astonishment, not least Zabel’s, he then nipped around the German a few metres short of the line to take the rainbow jersey.

But the sweet triumph was followed by bitter tragedy. Ten days later, Bettini’s role model and mentor, his brother Sauro, crashed his car into a wall two kilometres from where he and Paolo had grown up in La California, Tuscany. He died minutes after arriving at the hospital. He’d been arranging a celebration party for his brother.

Initially the grieving Bettini didn’t even want to start at Lombardia the following weekend. Having decided he would race, what followed proved to be the most remarkable and stirring performance of his career, if not of the decade in professional cycling. Having attacked alone on the Civiglio climb, 17 kilometres from the finish in Como, the world champion held off Gerolsteiner’s Fabian Wegmann and held back the tears, at least until victory was secure. He then tugged on the rainbow bands jersey and pointed heavenward. “Today I didn’t pedal alone,” he told reporters. If that were the case, we can thank the Bettini brothers for one of the greatest moments in Giro di Lombardia history. DF

Cavendish takes his first Tour stage

Tour de France, stage 5, 9 July 2008

A year earlier, Mark Cavendish had drafted a letter to his T-Mobile bosses pleading for his inclusion in the Tour de France. In the summer of 2008, the young sprinter’s chastening 10-day ordeal the previous year notwithstanding, he no longer had to convince anyone: Cavendish had ended the 2007 season with 11 victories, then raised his game yet another notch to bag his first two major tour stage wins at the Giro the following spring.

In July 2008 Cavendish stood at cycling’s equivalent of the Hillary Step; he would either stumble or else ascend to sprinting’s most rarified heights, winning for the first time at the Tour. His first chance should have come in Nantes on stage 3 but a three-man group was allowed to stay away. Two days later, on a searingly hot afternoon, the race pointed down into France’s central bread basket against a clichéd backdrop of wheat fields and sunflowers. Once again the sprinters appeared to have miscalculated as France’s Nicolas Vogondy barrelled under the kilometre kite alone, still several seconds clear.

Little did Vogondy realise that the wave of blue Columbia jerseys behind him presaged a watershed in world cycling. The tide had turned the moment Cavendish shot out of team-mate Gerald Ciolek’s slipstream. He passed Vogondy with 50 metres to go and slapped both hands on his head in disbelief as he crossed the line.

No one who had paid attention to Cavendish over the previous 18 months should have been surprised. As he had kept telling us, the braggadocio was really just razor-sharp realism, the hype all unvarnished truth. “This stage will be remembered forever,” he told us that night. Again, Mark Cavendish wasn’t wrong. DF

Voeckler stays in yellow by "guts alone"

Tour de France, stage 13, 17 July 2004

An oft-stated cycling maxim suggests that the yellow jersey lifts the performance of the rider who’s in it. Few have been lifted to quite the same extent as Thomas Voeckler during the 2004 Tour de France. The recently-crowned French champion was still a relative unknown when he joined a five-man break that went clear in the wet on stage 5 to Chartres. Race leader Lance Armstrong was happy to let the quintet go in order to calm a jittery peloton and leave the responsibility for defending the jersey on another team. With Voeckler more than three minutes better off on GC than his breakaway companions that was always likely to be his Brioches la Boulangère outfit.

More than 12 minutes up on the peloton in Chartres, Voeckler led the race for a week. The first real test of his mettle occurred on the first Pyrenean stage to La Mongie. He suffered badly but ultimately he lost only four minutes of his lead to Armstrong, leaving him with a buffer of more than five minutes going into a much more challenging run to Plateau de Beille. After the American won the day, the focus turned to the pain-contorted visage of the Frenchman, who confessed he was riding on “guts alone”

Aided by teammates Sylvain Chavanel and Jérôme Pineau, Voeckler kept the jersey by 22 seconds and held it for two more days. This stint was the making of Voeckler, who would become one of the super-baroudeurs. Among the gutsiest riders in the peloton, he soon became a national treasure. a second extended spell in yellow in 2011 cemented his status and confirmed that grit can be as vital as talent on even the greatest stage. PC

Marco Pantani entertains to the very end

Giro d’Italia, stage 19, 30 May 2003

With five kilometres left to go in the 19th stage of the 2003 Giro d’Italia – between Canelli and the summit finish at the Cascata del Toce – Marco Pantani dropped to the back of the main group before accelerating hard up the right-hand side of the road, crouched low, as always, on the drops of his handlebars.

Failing to get free, Pantani attacked again and again and then again. One final attack that saw him definitively lead a stage of his beloved Giro, before that year’s winner, Gilberto Simoni, took over, and Pantani faded to finish in 12th place on the day, 44 seconds down.

This was Pantani, and yet he looked nothing like him. He still had the earrings but they were attached to ears that had been surgically pinned back ahead of the 2003 season; Pantani’s riposte to the unkind ‘Elefantino’ nickname the others had given him. The bandana which had earned him the kinder name of ‘Il Pirata’ was also gone. His character was for the most part gone, and he looked like a frail old man as he crossed the line. Nine months later he would be found dead in a Rimini hotel.

But those famous ears would still have heard the cries of adulation from the roadside fans as he made his bid for victory that day in Italy. We heard them, too, as we watched the race from afar. The shouts echoed all around us: from the TV screen to the next table, where excited fists threatened to overturn coffees. It didn’t matter to those fans that he hadn’t won the stage; he had succeeded in recreating the Pantani of old, at least in a cycling sense, for a brief moment, and that, for them, was enough.

As the Procycling team emerged, blinking, into the light of a spring evening from the Italia Uno café on London’s Charlotte Street – where we’d often go to watch stages of the Giro when the offices were in London – we remembered only then that we weren’t actually in Italy. EB

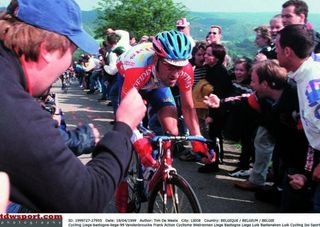

The Belgian supernova shines bright

Liège-Bastogne-Liège, 18 April 1999

By the time Frank Vandenbroucke won 1999’s Liège-Bastogne-Liège he had packed more into six years as a pro than most could ever hope in careers of a decade or more. In Belgium he was a supernova and he burned as brightly off the bike as he did on it. He lived, said a Procycling article at the time, at 200mph.

In 1999, the year he joined Cofidis, he found top gear at the carefree age of 24. He won Het Volk, a stage at Paris-Nice and another at the Driedaagse van de Panne-Koksijde. And at La Doyenne he was untouchable. He knew it and the peloton knew it and resented the arrogance which led him to tell journalists the night before the house number on the Côte de Saint-Nicolas – the final climb – where he would attack.

On la Redoute he stalked Michele Bartoli’s attack before prowling up to the Italian’s wheel in that silky, languid style of his before simply roaring away. It was as humiliating for the race’s defending champion as it was triumphant for Vandenbroucke. For the final hour, VDB played with the group that formed around him like a cat tormenting some mice. And on the Côte de Saint-Nicolas – just as he had predicted – he administered his coup de grâce and finished the race alone. If they’d dared not to think it before, Belgian fans now knew they’d found their new Merckx. Afterwards, at a ‘megabash’ thrown at his family-owned bar in Ploegsteert he partied like it was 1999 with team-mates. They would talk about it for the rest of the year.

Over the summer his relationship with his pregnant wife disintegrated. he was suspended for a connection to the dodgy doctor, Bernard Sainz, known in the peloton as Dr Mabuse. Yet after these setbacks he would return full throttle at the Vuelta and claim victory in two mountain stages in outrageous style.

But that was the brightest he ever shone. He succumbed to his cocaine addiction and spent what should have been the greatest years of his career fighting team managers, a drug habit and depression. In June 2007 he attempted suicide. In October 2009, while reportedly on the road to recovery from his mental demons, he died in Senegal of a pulmonary embolism. SD

Cipollini flies across the Flemish finishing line

UCI Road World Championships, Day 6, 13 October 2002

The Lion King raises two clenched fists in angry exaltation while dotted behind him members of the squadra azzurra echo the celebration in the remnants of the peloton at Zolder in 2002. Legendary Italian coach Alfredo Martini, 81 at this point and still on hand to help out, gushes, “Cipollini was grandissimo, like an aeroplano.” an abstinence from sex that Cipollini proudly revealed to the press has been worth it.

Aged 35, Super Mario was having one of the best seasons of his entire career. In March he’d won Milano-San Remo for the first time and taken six stages at the Giro. He had petulantly retired mid-season because of ructions with his team, Acqua & Sapone, and the denial of a Tour de France berth in July but returned at the Vuelta and took three stages before retiring again as the mountains loomed. In other words it was a vintage Cipollini season.

So some wondered if the powerful Italian squad would knit together effectively on that grey October day in Belgium. But under the gelling influence of their national coach, Franco Ballerini, the 12-man squad, plucked from no less than five trade teams, built a powerful lead-out train that left rivals such as Robbie McEwen and Erik Zabel fighting like dogs for the only wheel worth following: Cipollini’s. It was the fastest Worlds in history at 46.54kph.

In recent times Cipollini’s lustre has become tarnished by allegations of tax evasion and – more damningly – having paid in the region of €130,000 to Eufemiano Fuentes for EPO, testosterone and blood transfusions from 2001 to 2004, including two blood bags in the lead-up to Zolder. He always was the bad boy... SD

Most Popular