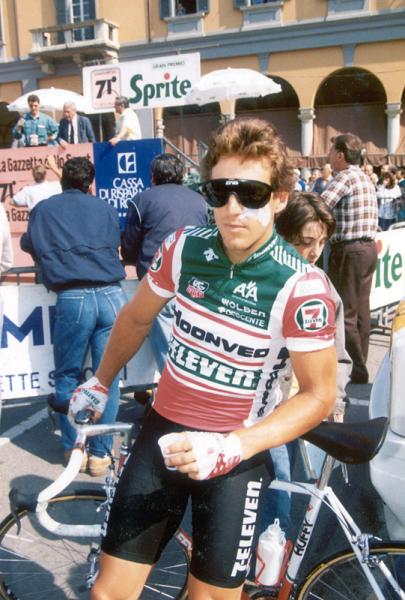

Davis Phinney and Ron Kiefel recall 7-Eleven team's wild ride in Milan-San Remo

Behind the broomwagon, stranded on the autostrada - a mix of misery and success in the American team's first Classic

This article of two Americans' adventure in the 1985 Milan-San Remo was first published on Cyclingnews in 2010.

Twenty-five years ago, the American 7-Eleven squad ventured to Europe early in 1985 to embark on the team's first bloc of racing in its debut professional season, and they were set to learn the ups and downs of racing in the European peloton the hard way.

The team opened its European campaign at Etoile de Bessèges, then competed in such events as the now defunct Tour Méditerranéen, Trofeo Laigueglia in February, then Milano-Torino and Tirreno-Adriatico in early March.

There was one more race which stood between the American team's inaugural foray to the Continent and a trip back to the United States: Milan-San Remo, the upstart squad's first true Classic, which took place on March 16, 1985.

"It had been such a tough spring for us since we were a first year pro team," Phinney told Cyclingnews. "It was really a fight for survival in all ways. You had to get to the race, and then all day you're battling for position and respect, and then you get to the hotel and you're starved, cold, and hungry.

"Every day you're waking up and it's more bad weather. This was way before teams had buses and laundry equipment, we're still sink-washing our clothes a lot of times and then your stuff never dries and just gets more and more grey. And your mood's also more and more grey."

The team was not without its mentors, however, as Belgian professional Noël Dejonckheere, riding for the Spanish Teka squad, visited the team in its hotel the evening before Milan-San Remo. Dejonckheere had finished Milan-San Remo in eighth place each of the previous two years and Phinney recalled the sage advice the experienced Belgian provided the American neo-pros.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"He said, 'You've got to eat A LOT, it's a long, long day and you don't want to run out of energy'. And after 160km you have to be at the front before the road narrows for the climb of the Passo del Turchino," said Phinney.

Phinney took the advice as gospel, and dutifully stuffed his jersey pockets with panini for sustenance, so much so that his rain cape could barely fit over his torso to protect from the rain buffeting the peloton as it left the Duomo in Milan.

As the race rolled along in its opening kilometres, Phinney devoured a panino every 10km like clockwork, fueling his body for the more than seven hours in the saddle facing the 25-year-old neo-pro. Much to the shock of Phinney, however, a certain Irish professional took exception to the American's eating habits.

"After about 60km Sean Kelly pulls up next to me while I'm stuffing my face. My gut is so full that my knees are banging into it while I'm pedalling. Kelly says, 'What are you doing? You're eating like a pig! You'll never make the finish like that'.

"I was just mortified, sitting there with a mouth full of food which I promptly spit out. I threw away all of my panini because Sean Kelly said I was eating like a pig."

Relieved of all his food, the race continued for Phinney as the peloton sped onwards to its first decisive juncture at the foot of the Passo del Turchino. Mindful of Dejonckheere's second piece of advice about being at the front, although simultaneously wondering about the wisdom of it since Kelly seemingly debunked the Belgian's first bit of insider knowledge, Phinney nonetheless fought his way to the front as if he was about to contest a field sprint.

But then disaster struck.

"As we came into the little town before the Turchino started I was on the far right side, in the second row, and we're just flying along. There's a sharp left turn and the pack drifted a little bit wide to the point where I was pushed off the road. I went flying off the road, crashed into this chain fence separating the road from the sidewalk and dislocated my finger.

"Eric Heiden saw me, stopped and I was just in misery. I told him, 'Pull my finger' but I have these thick winter gloves on and he couldn't get a good grip. Finally, he pulls it out, which was somewhat of a relief, but minutes have gone by and I've immediately just checked out in my mind. It's my first big race and I had completely failed."

At the Etoile de Bessèges, Phinney had nearly won the final stage and he later finished fourth at Milano-Torino. Only three days before Milan-San Remo a jubilant Phinney had finished second to Eric Vanderaerden in the final stage of Tirreno-Adriatico. The previous day the American was tickled to find himself named as a dark horse favourite for Milan-San Remo by Gazzetta dello Sport.

Now, a dejected Phinney soon found himself riding alone, with nearly the entire race caravan having passed him by, having given Heiden the green light to chase down the field without him.

Stranded on the autostrada

7-Eleven's director Richard Dejonckheere, Noël's brother, soon pulled alongside Phinney in a team car and gave him his rain bag chock full of extra clothing. Richard, too, was in low spirits, seeing one of his best riders out of contention. The Belgian told Phinney to soft pedal along until the broom wagon arrived and then sped away to rejoin the race convoy.

Phinney's first order of business was to figure out how to transport his rain bag, which was meant to be carried as hand luggage, without said bag swinging into his front wheel. Phinney decided to put it on like a backpack, an uncomfortable option which hindered the circulation in his arms, but at least he could hold the bars with both hands as he climbed the Passo del Turchino.

Phinney soon finds himself with three companions, a Dane, Spaniard and Belgian, all laden with their respective rain bags, all growing short on humour as they descended the Turchino and found themselves riding along the coast with still no sign of the broom wagon. They passed through the empty feed zone, with only the detritus of cast-aside water bottles and feed bags as evidence that a race came through, and estimated that they were at least 30 minutes behind.

"Here I am at this big race, Milan-San Remo, off the back with three other knuckleheads, still riding with race numbers on. I'm dirty, wet, cold and hungry, because I have no food, and we're still a long way from San Remo. We realized that we were screwed.

"The Danish guy, in total Viking-style thought process, said, 'I have a flight at 8 p.m. from Monaco, I have to be on it, and I am going now'. He just put it in his biggest gear and took off. The Spanish guy looked at the Belgian and me and said, 'I'm going with him' and he jumped onto the Dane's wheel."

Realizing that he and the Belgian would require at least two hours of hard riding to reach the finish, Phinney convinced his fellow straggler that their only hope was to veer off course to the nearby autostrada and hitchhike to San Remo.

"I was delusional and definitely out of my head," said Phinney. "This was well before cell phones, well before radios and we had no ability to communicate with anybody at the finish.

"We got off the course, rode up this hill to the autostrada, but we get stopped at the toll booth. The guy in the toll booth looked at us like two aliens have just landed from Mars. His dialect was just impenetrable. I spoke fairly good pidgin Italian but all I could do is show him our numbers and try to explain how we got lost. He just gave us this look of, 'Oh my God, who are you people?'

Unable to get onto the autostrada, Phinney and the Belgian proceeded to stick out their thumbs and unsuccessfully inquired of each vehicle arriving at the toll booth, "San Remo?"

"Of course, nobody has ever seen this kind of spectacle before, two pros thumbing it at a toll booth, and it's just getting later and later," said Phinney.

Hours passed by, the pair grew more and more dejected as they begin to see team cars speeding along the autostrada back to Milan, including a 7-Eleven vehicle, when suddenly the phone rang in the toll booth.

"Thankfully the toll booth operator had the wherewithal to understand our situation and he called the police in San Remo," said Phinney. "The police had somehow located Richard Dejonckheere in a 7-Eleven team car and Richard called the toll booth to say he's coming."

The 7-Eleven team director eventually picked both Phinney and the Belgian up at the toll booth, drove them to the hotel and filled them in on the race.

Kiefel's wild ride

Hennie Kuiper, 36, soloed to victory with a winning time of 7:36:34 for the 294km distance. Eight seconds later Kuiper's teammate Teun Van Vliet outsprinted Italy's Silvano Ricco for second place. The trio had attacked 12km from the finish, Kuiper was dropped on the Poggio, then clawed his way back into contact two kilometres from the finish. The Dutchman immediately attacked the pair, and rode alone to the finish. Belgium's Eric Vanderaerden won the bunch sprint for fourth, 11 seconds behind Kuiper, from a group of 64 riders.

7-Eleven's Ron Kiefel crested the Poggio near the front of the chase group and would finish strongly in the same time as Eric Vanderaerden. Kiefel was the sole 7-Eleven rider who made the split and finished at the head of the race.

While Phinney's placings in France and Italy prior to Milan-San Remo resulted in his dark horse status, Kiefel, too, was on good form. Kiefel earned the team's first European win a month before at the one-day Trofeo Laigueglia, beating reigning Italian national champion Vittorio Algeri by two seconds.

Kiefel also finished second in the Tour Méditerranéen's stage which concluded on Mont Faron and, along with Phinney, was the only other 7-Eleven team member to finish Tirreno-Adriatico, held that year in abysmal weather conditions.

Kiefel had a wild ride to San Remo in an experience unlike any other the 24-year-old had yet experienced in his nascent professional career.

"Nowadays there's a limit to 200 riders, but back then you'd have 300+ riders starting the race and it's just chaos," Kiefel told Cyclingnews. "It's just balls to the wall and all hell breaking loose racing to the Turchino. Guys were crashing everywhere and you were just trying to survive amidst riders taking big risks.

"When I first turned pro I didn't know what I had confidence in or didn't. I was worried about the 300km, I'd never raced that distance before. My longest race before was at the Tour Méditerranéen where we had a 220km stage.

"We didn't do any reconnaissance of the [Milan-San Remo] climbs and the finish. If we had it probably would have freaked us out. We just looked at the course profile and once we got out there in the race we just hammered. Ignorance was bliss for me at that point."

Kiefel was rightfully proud of his result in 7-Eleven's first European Monument, but the Colorado native soon found confirmation of his finish lost in a comedy of errors befitting a day in which his teammate was rescued from a highway toll booth.

"So in a perverse sense of justice which was favoring me and not Ron, the next day Ron gets 10 copies of Gazzetta dello Sport that he's going to bring home," said Phinney. "He's looking at the results and it said something about the finish line camera being broken. They basically hand picked it, just guessing who was who. They saw a 7-Eleven guy towards the front and assumed that was me. So there was my name as finishing in the top bunch of Milan-San Remo, and poor Ron was listed as 101st, hosed out of the result.

"I was looking at him, and he was crestfallen. I felt bad for Ron since I was given a finish in the top group while in reality I was at a toll booth with my thumb out trying to hitch a ride."

"I do remember the feeling of getting flicked by the race," said Kiefel. "Davis didn't finish and the Gazzetta showed him finishing, while I was nowhere. I was like, 'Oh man!'

Kiefel would not be denied his moment of glory, however, when 7-Eleven returned to Europe in May for the Giro d'Italia, its first Grand Tour. There was no mistaking the result in the Giro's 15th stage when Kiefel attacked late in the race for the victory and in the process claimed his spot in the record books as the first American to win a Grand Tour stage.

"It could definitely never be done these days because racing, budgets and training have evolved," said Phinney. "We had this really amazing window open to us in the 1980s and that led us to races like Milan-San Remo and the Giro d'Italia and then in 1986 to the Tour de France, which is pretty cool."

Based in the southeastern United States, Peter produces race coverage for all disciplines, edits news and writes features. The New Jersey native has 30 years of road racing and cyclo-cross experience, starting in the early 1980s as a Junior in the days of toe clips and leather hairnets. Over the years he's had the good fortune to race throughout the United States and has competed in national championships for both road and 'cross in the Junior and Masters categories. The passion for cycling started young, as before he switched to the road Peter's mission in life was catching big air on his BMX bike.