Ole Ritter – The mysterious hour record setter

Sometimes a rider turns up, startles the world, hangs about it a bit and then vanishes. After that,...

Tales from the peloton, February 8, 2008

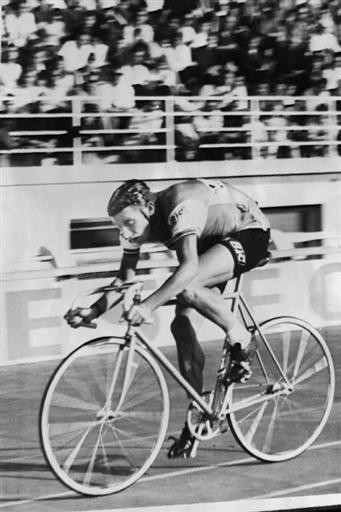

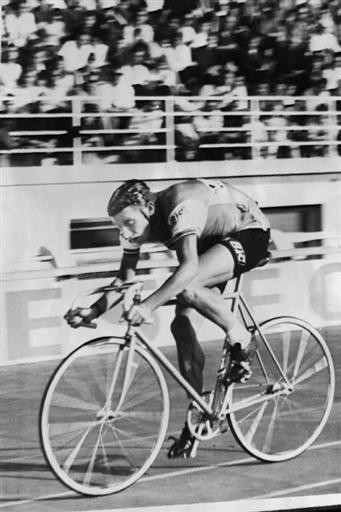

Sometimes a rider turns up, startles the world, hangs about it a bit and then vanishes. After that, it's as if he's never been. Except that he's left a record or an exceptional victory behind. Take the case of Ole Ritter. Forty years ago, he popped up unknown outside Scandinavia, broke the world hour record and did nothing of the like again until he dropped out of the London Six in 1978 and retired. Cycling historian Les Woodland takes a look at the mysterious hour record setter.

Ole Ritter used to work in a butcher's shop in Copenhagen. He rode a bike, of course, and he'd twice been Denmark's national road champion. But that was hardly a paying proposition and stripping pigs wasn't much better. So in 1965 he went off to Rome with a small bag and a bike... and broke the world 100-kilometre record – just like that. I suppose he must have told somebody he was going to do it but, if he did, the news didn't get far because the coverage outside Denmark was one of astonishment.

He was known to statisticians, of course, because he'd come second in the individual and the team time trial at the Amateur World Championships in Milan. But who remembers runners-up other than their mothers?

Ritter was still an amateur and the men who ran professional cycling in Italy rushed to the track to sign him. Ritter, however, had gone. The next year he turned up in Zürich, where he took the 10 and 20-kilometre records. The sponsors went to Switzerland, but again Ritter had gone. They looked for him in Denmark, but he'd already decided never to live there again.

They went back to Italy, where word had it he was living with his wife in the north, probably in Milan. But he wasn't there, either, because he was living in the south with a colourful businessman called Vito Taccone, a man whose talent in the hills had won him the Giro di Lombardia.

Taccone also caused a spectacular crash in the 1964 Tour de France, bringing down a heap of riders and concluding in a fight with Fernando Manzaneque and then his non-appearance in the Tour de France thereafter. His business record includes being charged with selling stolen clothing in June 2007, four months before his death.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Ritter turned professional in 1967 for a team called Germanvox, run by a company that made telephones. It was hardly what you'd call one of the great teams of world cycling, although it did include the colourful Taccone, and it lasted just three seasons. In that time it got full value from its dark-skinned Dane.

For a start, Ritter rode the Giro d'Italia in 1967 and flattened Eddy Merckx, Jacques Anquetil, Felice Gimondi and Ferdi Bracke in the time trial. They all got soaking wet, because it poured all day, and that didn't improve their mood. But Anquetil, although incredulous, didn't hide his appreciation. If the time trial had been accurately measured, he said, Ritter's 47.3km/h would be good enough to beat the world hour record.

Anquetil, who beat that record twice, knew what he was talking about.

Ritter by now was becoming as much Italian as Danish, and the following year he joined the Italian amateur team on its trip to Mexico, to get used to the altitude for the Olympic Games there. He was a guest, though, a foreigner, an outsider, and although the Italian coach, Guido Costa, was happy to help him, the Italian riders weren't keen to give up their track time for him.

When they did, on the morning of October 10, and only then because the Games started next day, Ritter pushed away at 10:27 and rode 48.653 kilometres by the time the time the clock turned the hour. It was 560 metres better than Ferdi Bracke had ridden in Rome.

The new figures obviously delighted Ritter but they pleased Anquetil even more. The previous September, Anquetil had broken the record at the Vigorelli in Milan. It had stood for nine years to another Frenchman, Roger Rivière. Rivière said afterwards that he had stuffed himself full of drugs to do it. There were fears that Anquetil would do the same, and so he was told before he started that he would have to give a urine sample at the finish. Anquetil never did fill the bottle, not because he especially objected but because he wouldn't do it in a small tent in the middle of the track as thousands of jeering Italians looked on. Dignity had its price, and the price he paid was for his record to be dismissed.

He and his manager, Raphaël Géminiani, went to court over it but things had barely started when a nervous, grey-haired Belgian, Ferdi Bracke, beat his figures anyway. Anquetil never recovered from the hurt and it's impossible to imagine that he didn't have at least a twang of pleasure when Ritter lifted the record off him.

The other point is that Mexico City was up in the clouds. The thinness of the air led to predictions of awful things happening to competitors at the Olympic Games, but it also meant that no end of records were broken. Among them, the world hour, the five, the 10 and the 20-kilometre, the last three broken by Ritter in the days before his hour ride.

André Dirix, the Belgian doctor and anti-doping campaigner who was there in Mexico when Ritter broke the records, said that not only would the lower air resistance make the ride easier but that altitude reduced the weight of the rider and his bike.

Merckx established his hour record at Mexico, in 1972. So did Francesco Moser in 1984. The difference between them was that Merckx rode on an ordinary bike, as Ritter had, whereas Moser rode on what passed into history as his "funny bike." Just as significant is that some time later the International Cycling Union (UCI) began having doubts about the way things were headed. If everyone had to ride a bike that only the stars could afford, and if they had to go to Mexico and other exotic tracks to do it, what value was there left in the most prestigious of track records?

Nobody again broke the record in Mexico. Ritter was the start and Moser the end. A massive change in cycling happened between them.

One more thing about Ritter. In 1974, when he had turned 33, he went back to Mexico. Sure, he didn't beat Merckx's record. But he did beat his own record, the one he set six years earlier. And he did it twice in a week: 48.739km and 48.879km. Not bad for a guy that hardly anybody remembers, eh?