Joe Papp: From drug dealer to anti-doping advocate

American escapes prison, hopes for redemption

Papp reached levels of notoriety his racing career never matched when he testified in the Landis case of 2007. A doping suspension later and Papp was facing up to ten years in jail for trafficking drugs. Now free from jail time – but with a suspended sentence – the American says he's an anti-doping advocate. With the war on drugs an ongoing battleground could Papp be one of cycling's most important losers?

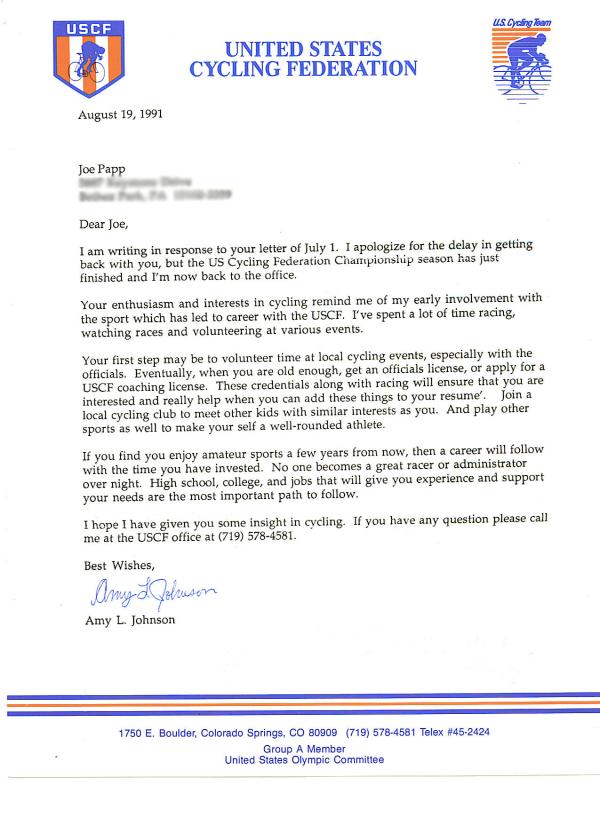

At the age of 15 Joe sends a handwritten letter to United States Cycling Federation. He asks what will happen if he doesn't make it as a professional rider. Will he still be able to stay in cycling and in what capacity?

Some time later a response comes. It's encouraging and Joe smiles, gripping it tightly as he reads to its conclusion. He folds the letter up, puts it back in its envelope and finds a safe keeping place for it. That night Joe goes to bed but struggles to settle. All he thinks about is cycling. The letter wasn't a rejection and it gives him hope. At 15, cycling is already his passion and it's his life.

In 2007 Joe is still involved in cycling. He's not a professional bike rider, he's not an advocate for cycling and he's neither a coach nor a team manager. Joe's a drug trafficker.

He facilitates in the supply and demand of EPO and growth hormone. His clients tally close to 200 athletes and are spread across the globe and although he makes a decent living from his criminal activity he's perhaps at the centre of one of the sport's biggest drug scandals, with clients from the pro and amateur ranks.

Upon leaving a college class one day in September 2007, Joe receives a text message from his brother. "Come home Joe. Come home. You've been raided by the cops."

"I thought he was joking at first," Papp now tells Cyclingnews.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"The house itself wasn't turned upside down, it was just my office and bedroom and they really aren't very neat about it," he says, almost surprised. Police authorities had turned up looking for Papp after being informed of his activities. Working for the Shandong Kexing Bioproducts company, he had files and other material that had him banged to rights.

Joe didn't return home that evening and describes those few hours as "the absolute worst moment of the entire process", deciding to lay low and seek legal representation the next day. A number of items were taken: a computer, a few boxes with files, and a collection of other personal items.

Waiting for a sentence

In the subsequent few years, Papp, who already struck a level of notoriety within the sport after testifying in the Floyd Landis case, has had to bargain and fight for his freedom. Under US law his offences could have netted him up to ten years in federal prison. However, after pleading guilty to his trafficking offences in 2010 he has helped investigators and USADA with several related and unrelated doping cases.

Think Zajicek, Leogrande and Chodroff, to name but a few. All three have been banned for doping offences. All three were clients of Papp.

Logically, after pleading guilty Papp should have been sentenced soon after but that delay was due to his continued cooperation.

"I was never arrested but from the time the government notified me that I was in trouble, back in September 2007, I was cooperating in whatever way I could. A principal reason for why it took so long and then why it was delayed so many times was because of the ongoing nature of the cooperation."

"They could have sentenced me a couple of weeks after I pled guilty in February 2010 but in the end it was almost 20 months."

What led Papp towards the downward spiral and into trafficking drugs isn't totally clear. Already a convicted doper and banned from competing, Papp had also set about providing drugs to teammates.

When based in Italy as a rider, he was helping teammates buy EPO for themselves. But once back in the States in August 2006, all of the clients came anonymously online. He didn't know their names, often they would use fake identities and addresses or in Zajicek's case, a lover's profile.

"You go from helping your teammates with EPO to helping strangers with EPO, that doesn't need a huge leap in logic because you're doing it whatever the reason whether it be for profit, importance or help. You're still essentially doing the same thing," Papp says, explaining his reasoning.

"It was so connected and similar to the indoctrination into doping as a rider and if you really think about it, pretty much everyone who is involved in doping and an athlete at that level was trafficking to some degree because even if you're sharing products amongst your team you're doing the same things, and that's how it started for me."

"Another rider introduced me to the source in China and to make it easier to get EPO for my own needs it was almost like offering a convenience to my teammates who wanted to do the same thing. I don't mean that to my credit."

At this point it's probably not hard not to take a dislike to Papp. If you're a professional bike rider who is clean, a fan who believes the sport deserves better or just someone with a vaguely stable moral compass, his actions appear destructive at worst, and weak at best. He says that part of him was relieved to have been caught but it's unclear if he truly would have stopped had lawful intervention not taken place.

"It would be understandable if people wanted to characterize me as something extremely negative but I would hope that someone would look at it and see that while there was a lot of negativity created at the same time they think I responded in the most honourable way possible."

"I didn't deny what I did or pretend that it wasn't happening and I did the best that I could to help the authorities to technical aspects and the psychological components and why things were happening and how to better combat them."

"I would hope that people look at what came after my trouble. It's been four years that I've been cooperating and done everything I could. It's not been in the public eye but I wouldn't have got the sentence I had if it had not been to this unprecedented degree."

The Future

And this is certainly true. Papp escaped prison, receiving a suspended sentence and a period of house arrest. But whether born out of self-interest and protection or a true sense of correcting his mistakes and helping the sport, it seems that Papp's new place as an anti-doping advocate is a warranted one. Why? Because it gives him all those things he desired as a 15-year-old boy. In the world of cycling, simply put, he has a purpose.

Does he deserve one? So far Papp has cooperated on between 15-20 cases. That's essentially 15-20 dopers struck from the bunch, whether they were clients of his or not. The war on drugs isn't pretty: it's relentless, cruel and at times callous. If having Papp on the side of good means that more dopers are caught, that's a cause for appreciation.

"I can tell you that I absolutely at no point wanted to go to prison and that at no point was I going to do anything less than the absolute maximum to help myself," he says on the one hand.

"There's nothing noble in accepting a prison sentence but in time I came to believe the message that went along with that cooperation, because my involvement in doping ruined my life in a lot respects. There's no way I would wish someone else to make that same mistake, so anything I can do to stop them from going down that path, I'm going to do humbly and honestly. I'm committed to the anti-doping fight and right now it's not because I need to cooperate but because as long as doping is illegal I'll do everything to stop it."

"When the degree of my involvement in doping was made public the response was extremely negative from the cycling community. There were people who were supportive but the majority of people were hostile. Over the years as people have realised the sincerity of my effort as I've cooperated and the fact that I'm genuinely contrite, people are overwhelmingly supportive," says Papp.

Now under house arrest, Papp is only allowed to leave his premises for food and essential needs. If he wants to see family and friends they must visit, if he wants to go to the movies or to have a meal out, he can't. Still, it's a future that is far brighter than the one he could have faced if he'd gone to jail.

"I wasn't prepared to go. I mean I thought about it everyday and I worried about it everyday but there was nothing I could have done to help me get through it. I came up with some plans of what I could have done when inside but nothing prepares you mentally for that loss of freedom and liberty. House arrest is inconvenient but it's nothing or comparable to what prison is. I can't tell you how grateful I am."

Papp was so determined not to face jail that he considered suicide but now that the prospect is a memory he must pick up the pieces of his life. Doping and trafficking brought in small gains when compared to legal fees and years without work, and understandably he finds his at an important junction.

But Joe, that 15-year-old boy who sent that letter to USA Cycling all those years ago, might not walk away just yet. Several days after his sentence, Papp met with the DEA and was handed back belongings they'd seized from him in 2007. Joe wiped the dust from the computer screen that was returned to him, flicked it on and went browsing through files he hadn't seen in year. And he found a scan of that letter he wrote as a child along with the response.

"It's going to be hard not being connected to cycling," he says when discussing the future.

"Cycling motivates me and gives me a sense of purpose and meaning that I don't really feel from other pursuits. I don't know why that is but that's how it has been and how it's always been.

"I would like to have a fulfilling life off the bike, but that could be more difficult that being a rider or even being a drug dealer. I don't think I've lost the right to enjoy the actual act of pedalling a bike as a fitness endeavour, and something that is therapeutic. If I can also be an anti-doping advocate in the sport of cycling, well that's something I don't think I've lost the right to do."

Keep that letter close.

Daniel Benson was the Editor in Chief at Cyclingnews.com between 2008 and 2022. Based in the UK, he joined the Cyclingnews team in 2008 as the site's first UK-based Managing Editor. In that time, he reported on over a dozen editions of the Tour de France, several World Championships, the Tour Down Under, Spring Classics, and the London 2012 Olympic Games. With the help of the excellent editorial team, he ran the coverage on Cyclingnews and has interviewed leading figures in the sport including UCI Presidents and Tour de France winners.