1998 Giro d'Italia: The apotheosis of Marco Pantani

A look back at the final moment of uninhibited, innocent celebration of a national sporting hero in Italy

With no Giro d'Italia to look forward to this May, we're delving back into the history books to re-live some of the most compelling storylines from the Corsa Rosa, with a mixture of original and archive content.

This article was originally published on Cyclingnews in April 2018, as part of our countdown to the 101st edition of the Giro.

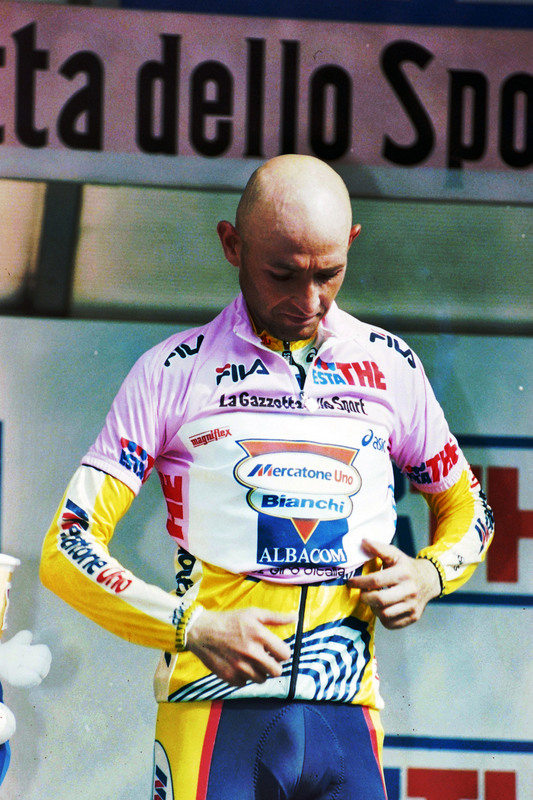

Marco Pantani's victory at the 1998 Giro d'Italia marked the apotheosis of his roller-coaster career, the sporting high-point of his tragic life story and the final moment of uninhibited, innocent celebration of a national sporting hero in Italy.

Pantani went on to win the 1998 Tour de France and so completed a historic Grand Tour double. But that race was marked by the Festina Affair, doping raids, arrests, scandals and a feeling that things finally had to change. It was the end of a doping era, even if Lance Armstrong quickly ushered in another.

The 1998 Giro d'Italia was Pantani's personal Icarus moment, before his dramatic downfall precisely a year later when he failed a haematocrit test in Madonna di Campiglio and was disqualified from the race while wearing the maglia rosa. Soon after, he started to use cocaine, lost the desire to race and train, blamed everyone but himself for his problems, and started a downward spiral that would ultimately lead to his death on St Valentine's Day in 2004.

Twenty years on from the 1998 Giro d'Italia and 14 years since his death, Pantani remains an almost legendary figure in Italy. His mother Tonina is still fighting to defend her son's honour but has gradually moved from denying to accepting that her son probably took EPO like most other riders in the 1990's. Pantani's death stopped him from growing old and revealing what really happened during his tumultuous career. His teammates and friends remain in embarrassed silence, preferring to let Pantani rest in peace.

Everything was so different and so naturally joyful for the tifosi in May, 1998. EPO abuse was widespread, despite the introduction of the haematocrit test, but Pantani seemed untouchable. The full extent of the use of EPO and other doping methods was still mostly unknown to the Italian public at the time. They only saw Pantani's melancholic smile and admired his ability to attack all his rivals in the mountains and solo away to victory.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

He was considered a skinny, climbing David, taking on the Goliaths of the Grand Tours. He was someone to cheer for, a nice guy who was losing his hair even in his twenties, who had risen from his humble roots on the Adriatic coast to inspire a generation and a nation.

Taking on Zülle, defeating Tonkov

Pantani recovered from a broken leg and made a successful comeback in 1997 but crashed out of the Giro d'Italia when a cat ran into the peloton. He recovered to finish third at the Tour de France, winning at L'Alpe d'Huez and Morzine. After his early success in 1994, he seemed on the cusp of cycling greatness in 1998, ready to become 'Il Pirata'.

The 1998 Giro d'Italia started in Nice and ended in Milan, after three weeks and 22 stages of racing. There were no rest days that year, and no one complained; EPO made the daily fatigue more bearable.

Alex Zülle and Pavel Tonkov were Pantani's biggest rivals for the maglia rosa. The Swiss rider led the Festina team, while the quiet but determined Russian captained the Mapei team. Pantani was protected by his loyal Mercatone Uno teammates, with Giuseppe Martinelli again acting as directeur sportif.

The 3,811 kilometres of racing included three time trials for a total of 84km against the clock. Zülle, the winner of the 1996 and 1997 Vuelta a España with ONCE before his move to Festina, was confident of overall victory, while Pantani was hoping to at least win a mountain stage after crashing out in 1997. The Italian tifosi were naturally on Pantani's side, keen to see one of their own triumph.

Zülle won the time trial in Nice, gaining 39 seconds, but Pantani replied by attacking whenever possible, even on the Capo Berta climb before the stage 2 finish in Imperia. Pantani knew that Zülle would gain minutes on him in the two time trials and could only hope that a long spell in the pink jersey would slowly fatigue the Swiss rider and his Festina teammates.

Zülle won stage 6 and extended his lead, but Pantani responded by attacking and winning stage 11 to Piancavallo.

"I take risks and attack, that's why the tifosi love me. This is the start of my race, and Zülle should be afraid," Pantani said after the stage. He was often quietly spoken and reflective but never afraid to respond to his rivals.

However, Zülle responded out on the road by winning the next day's time trial in Trieste. He caught, dropped and humiliated Pantani, gaining 3:26. Pantani fumed but refused to admit defeat, knowing that a Trittico of terrible mountain stages were still to come.

"Non e' finito (It's not over yet)," he insisted.

Pantani in Rosa

Stage 17 to Selva di Val Gardena included the Passo Duran, Forcella Staulanza, the Marmolada and the Passo di Sella. According to Matt Rendell's excellent Pantani biography, Pantani asked teammate Roberto Conti when the Marmolada began, only to be told they were already halfway up the 14km climb.

Pantani soon attacked, getting away with Giuseppe Guerini as Zülle cracked and Tonkov suffered. Pantani gifted Guerini the stage but gained over four minutes on Zülle and so pulled on the pink jersey for the first time in his career. He kissed the maglia rosa and beamed a big smile in a rare show of pure happiness.

Pantani in pink was front-page news on every newspaper in Italy and on every news bulletin. Pantani-mania was in full flow. An estimated one million fans packed the roadside and thousands of others decided to head to the mountains to be part of what felt like a historic moment.

The next day Tonkov confirmed he was Pantani's new threat as Zülle lost more time on the steep finish to Alpe di Pampeago. The Russian was only 27 seconds behind in the general classification, with Zülle at 2:08, and Pantani knew he would need to pull another "impresa (epic ride)" if he wanted to win the Giro. Fortunately, stage 19 finished up at Plan di Montecampione after 243km of racing.

The finale of the stage is now legendary. Zülle cracked entirely and lost half an hour. Pantani and Tonkov fought like boxers on the twisting climb to the finish, with il Pirata - in the pink jersey - landing a series of attacks and accelerations, only for Tonkov to respond each time and stay in the fight.

"Either I'm going to blow up or he will," Pantani told himself, even throwing away his diamond nose stud before the decisive attack with three kilometres to go. Riding with his hands in the drops in his usual attacking position, Pantani gained a metre, then two, then more. Tonkov could suffer nor respond no more, the elastic snapped, and Tonkov's head bowed in defeat. Pantani went on to gain 57 seconds and extended his lead on the Russian to 1:27.

"Tutta Italia urla: Pantani! (All of Italy screams: Pantani!)" was the headline in Tuttosport, with 4.5 million Italians - 51 per cent of that day's television audience - glued to their televisions to cheer on Pantani.

The 34km time trial from Mendrisio to Lugano was the final obstacle between Pantani and victory at the Giro d'Italia.

The tension at Mercatone Uno matched the excitement of the fans, especially following the expulsion of teammate Riccardo Forconi for a high haematocrit. Pantani raced with a bandage on his arm after also undergoing a blood test. According to Rendell's book, Pantani's blood value was 49.3 per cent - scarily close to the 50 per cent limit.

Almost a year to the day in 1999, Pantani's blood haematocrit was measured at 52 per cent at Madonna di Campiglio, and he was disqualified from the race while wearing the maglia rosa. However, in 1998 Pantani seemed untouchable and unstoppable. He even gained five seconds on Tonkov in the time trial and rode into Milan the day after as the winner of the 1998 Giro d'Italia.

His Mercatone Uno teammates shaved their heads in celebration. Some 40 days later, they coloured their hair yellow as Pantani also won the Tour de France in equally dramatic fashion after attacking Jan Ullrich on the Col du Tourmalet.

Italy again celebrated a national hero. Little did they know how Pantani had managed to climb so fast.

Twenty years on, most Italian tifosi, blinded by the emotions of 1998, still don't care.

Stephen is one of the most experienced member of the Cyclingnews team, having reported on professional cycling since 1994. He has been Head of News at Cyclingnews since 2022, before which he held the position of European editor since 2012 and previously worked for Reuters, Shift Active Media, and CyclingWeekly, among other publications.