Filippo Pozzato: I wasted my talent for too long

Q&A with Tour of Flanders contender

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

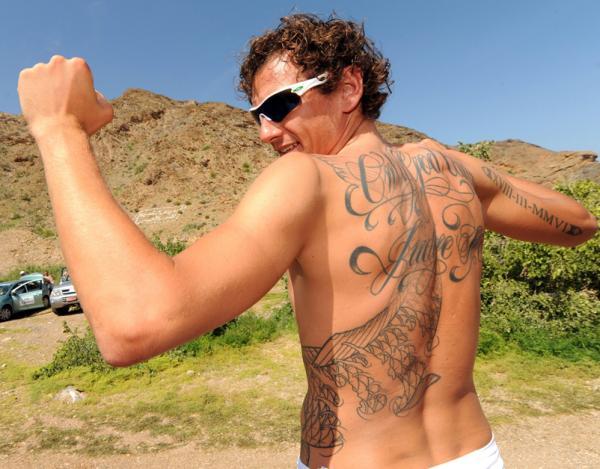

Dismissed by many as a washed-up playboy, Filippo Pozzato has overcome the odds and a broken collarbone to find something approaching his best form on the eve of the Tour of Flanders. Earlier this month, the night before the Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, Pozzato spoke at length to Daniel Friebe about his injury, moving to Farnese Vini-Selle Italia and squandering his talent for far too long.

*A fly-on-the-wall account of Pozzato’s 48 hours at Het Nieuwsblad and Kuurne-Brussels-Kuurne appears in this month’s Procycling magazine.

CN: Filippo, after your crash and broken collarbone at the Tour of Qatar, your Classics seasons already looked to be jeopardy. Instead, the following weekend you were racing at the Trofeo Laigueglia....

FP: The doctor told me to stay off the bike for a month, to give the bone time to calcify. The problem was that I couldn’t do anything for 40 days. I got angry with the doctor. I came back from Qatar on the Friday night, went into hospital on Saturday morning and told him to operate straight away. He said that was impossible, that I had to wait for 10 hours. I told him that I couldn’t wait ten hours, that I needed to be aback on my bike in three days and racing at the weekend. He asked me whether I was mad. My girlfriend said I was mad, too, but it was such a crucial point of the season. Even [Farnese Vini-Selle Italia directeur sportif Luca] Scinto didn’t want me to race. I said that I’d put my balls on the line and I wanted to give this everything. I told him that this was my decision. I didn’t want to lose anything, even psychologically – you know that after a week off the bike you start to lose your condition. In the end I was back on the bike after four days. I think I made the right decision. I either stopped for a month and threw away the whole first part of the season, or I did what I’ve done. Everything or nothing. There could be no compromise.

CN: If this had happened in any other year, we get the impression, you’d have reacted differently. Are we right?

FP: If this had happened to me in any other year, I’d just have listened to the doctor and stopped. But this is make or break time in my career. I made a choice [to come to this team] – a lot of people didn’t agree with it, because I could have joined a number of other ProTour teams – and I’m sure it was the right choice. But there’s no room for error any more. I can’t afford to say, ah, it’s no problem, we’ll see how I goes. I have to do everything I can now. Getting back on my bike came naturally to me and I didn’t even think. It would have been easier to throw my arms up and say, “Ah, more bad luck”. But when I get something into my head, I’m quite stubborn.

CN: But weren’t you in pain? Your shoulder had to be opened up and secured with metal pins. Like you said, usually the recovery time is 40 days.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

FP: It hurt a bit but behind, where I fell. The thing that no one understands, but that us riders know well, is that when I fell I hit my pelvis and that twisted everything, so my back was hurting. The guy who operated was really good but I’m lucky to have a masseur, Michele del Gallo, who’s a magician. He can see straight away what my problem is, and he can solve it. In two days he’d sorted me out.

CN: It seemed from the outside that all the support you got from the public, particularly on Twitter, galvanized you to come back quickly. Your move to a smaller team, Farnese Vini, seems to have boosted your popularity in Italy. Having been portrayed in the past as a mollycoddled underachiever, you’ve suddenly become a plucky underdog.

FP: The public loved me moving to Farnese, the cycling world less so. But when I moved, it was because I had certain guarantees. Without those, I would never have moved. People in cycling criticized me over the races I might or might not do, but I’d already spoken to the organizers of those races. I knew what I had to do. It wasn’t a question of, whatever will be, will be, and let’s just cross our fingers. I was sure that I was going to do certain races, otherwise I would never have signed. I think the public understood this. The press, on the other hand, have always misunderstood me a bit. And it isn’t just the press; it’s anyone who doesn’t know me well. They get this impression that I don’t care about cycling, that I’m too concerned with all the trappings of success. But I think my problem has always been finding an environment where people have faith in me. If I can feel that, I can give 110%. But if someone starts nitpicking about something silly, I can only give 50%.

CN: As time has gone on, you must have felt or noticed that everyone’s faith in you has slowly ebbed.

FP: Winning is easy when you’re young. Expectations are the hard part. When you’re 30, you can deal with it, but when you’re 20 you don’t have the resources. In your head, you’ve already moved up to the next level, you’re already better than the rest, so then you don’t work as hard. And this becomes a limit. You’re better off being less physically gifted and stronger in the head. That’s better than being a phenomenon, having ‘class’ as they say – this was my problem. I’ve realized this now. I knew that I had a bit more than the others. I could say to myself, ah, you don’t have to worry about doing this or that, because you’ll be strong anyway. I’m finally learning now. For example, last year at Milan-San Remo, I knew that I didn’t have good legs because I’d realized that I’d been training badly – or using the wrong method, the one the team coach had given me, which was totally different from what I’d always done before. I did everything badly, I went to the Tirreno and I was fat, because I had 3 or 4 more kilos of muscle, but then I went to San Remo and I was at the front anyway, even though the day before no one would have staked a lira on me. When you commit to something, you can get three or four per cent more than the others. But I’ve got to the point where I know that all of the potential I’ve had, all of the talent, I have to exploit it because, if not, it’s like the parable of talents in the Bible: if you don’t exploit them, you throw everything away.

CN: But it’s taken you a decade to realise this. Why so long?

FP: It took me a long time, too long, without doubt. I still got good results because I was always ahead in races. But maybe I couldn’t do that extra thing which allowed you to win races. I understood this last year, when I had a bit of time away, a bit of time to reflect. I asked myself whether I wanted to give up. Because there was a time when cycling made me a bit nauseous. I took no pleasure in cycling any more.

CN: And at the same time there were issues with your old team, Katusha, and in your private life…

FP: There were other things. This time last year I talked about a “momento di merda” – a really shitty time. I’d split up with my ex-girlfriend. That happens, you lose a reference point, and you’re destabilized. We’d been together for 8 years and it becomes the bedrock in your life. It’s a bit of solidity. When you lose that, you get lost in a bit of a fog. I was only sleeping two hours a night.

CN: This is in spite of your reputation as a “ladykiller”. People would perhaps assume you loved being single…

FP: The press have always really emphasized that side of my persona. It was good and I profited from it when things were going well, but when they weren’t, the media used it against me and the coin flipped. It was a gimmick which could help me sometimes and hinder me at others. So now, with journalists, I’m really trying to open up and show them what I’m really like, what I really feel, so they see that I’m no just cars and watches and women. I’m here because I like what I do. Cycling’s hard, you suffer a lot in races, but the fact is that, if I didn’t have it, I’d be unhappy or ill. That’s bottom line. I don’t do if for money. I’m 30 years old – of course there are other things in my life. I’m also the first to admit that they were right about certain things. I’ve always done a lot but sometimes I haven’t done everything I could have done.

CN: It’s been said in the past that you’re too sensitive to be a really successful rider.

FP: When you’re sensitive in a lot of ways – not just towards your girlfriend – but also have the sensitivity you need to understand what people think of you, or the sensitivity you may need in a friendship, I don’t think that’s a limitation but a tool, if you know how to use it. But it’s delicate. Marco Pantani was very sensitive, in a good and bad way – more bad than good in the end. He was extremely sensitive, but he cut his own legs off with that sensitivity. Rather than do that, you’re better off being someone who doesn’t give a shit about anything or anyone. But I’m happy with the way I am. I wouldn’t change myself or my life for anything in the world. Understanding myself as I do now, I think I can turn the sensitivity into an advantage.

CN: What went wrong on the road last year, in particular?

FP: Last year was just a vortex. A succession of negative things which came together at the same time and made life very difficult. If I survived that, I say to myself that I can survive anything. Now my attitude is, 'if there’s a problem, right, let’s solve it and move forward'. Not, 'ah, I don’t know if I can be bothered any more'. Problems are there to be solved, not to make a tragedy out of. But last year, yeah, with what was happening with the team, and in my private life, I felt squashed. Then, when I got injured at the Tour of Belgium, I was on the floor and I said to myself that either I got back up or I gave up. In the end I came back, won again and had a good winter, worked well and so on. This year in February, I was already going quite well in Qatar. I’m convinced that I could have been really good at Laigueglia. But then the crash happened and even the team was worried. Having made the investment, they were concerned. The pressure that put on me wasn’t a burden, but I did feel the need to pay them back.

CN: This time last year you were at loggerheads with the Katusha manager Andrei Tchmil. What went wrong between you two?

FP: The problem with Tchmil was this: I’d had a problem in my private life and he didn’t give a toss. The break-up had happened in the spring of 2010. Then, at the end of the season, there were technical problems, things that I wasn’t happy with, and that was the biggest problem. From that point on he was against me in everything. When you’re already struggling because of things happening off the bike, and you know you have to go and do a certain type of race, it’s hard when not only are you not being supported technically, but the team is actually against you. It got to the point where we were arguing at every race. Then we got to the Giro, he didn’t pick me for the Giro, and that was it as far as I was concerned. I washed my hands of it. From that point on we didn’t even speak. I’m not going to slag him off, even say that he was wrong and I was right. I think we both have strong characters, and above all he has a big weakness: he doesn’t want to listen to anyone else. Never. If he wants to go straight on, you’d better go straight on, otherwise there’ll be trouble. I’m stubborn as well but sometimes I listen to what other people have to say. That was the problem: the communication broke down. But at the end of the year, I went to his farewell party. He called and I went. Because we actually got on well for a year and a half. It’s not like I was unhappy there. At first most marriages are happy, then the love ends.

CN: You say the problem was a technical issue. You mean the bike?

FP: Yeah, it may seem strange that the bike caused such a big fall-out, but it did. I’ve never understood why cyclists are always satisfied with the equipment they have, or at least say they are. It’s not like that in Moto GP or F1. Why? I don’t know. Because very often we’re made to use equipment that’s not good or suitable. This year is maybe the first time that I’ve been really happy, and that’s a result of the team listening to me. What this team had last year wasn’t quite good enough, in my opinion, and they changed it to make me happy. Now I’m 100% satisfied. But, yeah, it’s ridiculous that we’re just given a bike at the start of the season and have little if any choice in the matter. Valentino Rossi has made Ducati completely overhaul their bike. I don’t see why it should be different here.

CN: Your relationship with Scinto seems an odd one. You have this suave, sophisticated image, whereas his is a little more…rustic.

FP: Scinto and I are opposites. We haven’t had a proper fight yet but there have been differences of opinion. We argued a lot about me riding Laigueglia. We’re so different…but there’s one thing that unites us: our passion for cycling. Because without cycling, Scinto couldn’t live. That’s for sure. And although it might seem from the outside that cycling isn’t everything for me, it is fundamental in my life. It’s the main thing for me in this period of my life. Maybe this is why I went with him: because I could see how passionate he was, how he gave 100%. But yeah, we could hardly be more different.

CN: How will the changes in your mentality this year manifest themselves? How do they need to manifest themselves?

FP: I think I need to have the legs I had in my best periods and the head, the mentality of when I was young and riding to win all the time. I can see already that I’ve changed a lot mentally, compared to other years.

CN: You’ll be surrounded by fairly inexperienced riders in the Classics. Wouldn’t you rather be riding for Sky or BMC?

FP: I’m happy where I am. I wouldn’t want to be riding for BMC in the Classics. We’ll see. They definitely have the strongest team – but we’ll see how they race. It’s difficult, being the favourite. But I think Omega Pharma is a fine team too. I actually think Omega Pharma are stronger at the moment [in early March]. It’s a team built around an individual, Boonen. At BMC, on the other hand, they all want to win. No one knows what they’re supposed to do there, whereas at Omega Pharma they maybe have three of the best domestiques in the world. At BMC, if one moves, all of a sudden, the others all have their hands tied and they have to do jobs they’re not used to. I wouldn’t like to be them.

CN: Are you pulling up a stool in the Last Chance Saloon? That’s what it looks like…

FP: On paper, if I was someone else looking at me and my career, I’d say that this is my last chance. But, even if that is the reality, and it’s probably not, the thing doesn’t weigh me down. I find the position I’m in stimulating, not suffocating. I don’t feel like my back’s against the wall. I don’t feel like, if I get it wrong this year, it’s all over. I know it’s crucial, this year. I can’t be a 'prospect' until I’m 36 years of age. This year I have to show what people expect of me, but above all what I expect of myself. My plan is to do three really good years now, years like this one was shaping up to be. I want to do three years with the determination and nastiness to win races.

CN: So, in summary, you think that you took your talent, your “class” for granted. And that’s over now…

FP: I did, I took my talent for granted. And I’ve found out over the past couple of years that as soon as you take anything for granted, in life and in cycling, you get screwed. So it’s better if you’re always hungry to show who you are and what you’re worth.