Danny Nelissen: The flying Dutchman who conquered the Andes

The story of the last amateur World Championships in 1995

The following feature forms part of our 'I love the 1990s series' with Alasdair Fotheringham going back to the final amateur World Championships in 1995 to speak to race winner Danny Nelissen. The Dutchman, plagued by a heart condition during his career, was one of the first riders to seek technological advantages and used those methods to pull off one of the finest wins witnessed at a major championships.

For many, the 1995 World Championships men’s professional road-race in Duitama, Colombia is remembered as one of the most spectacularly brutal in cycling’s modern-day history. The wet weather, racing at altitude 2,500 metres above sea level and the staggering amount of climbing demanded by the road circuit allhelped lift the 1995 Worlds to a level of difficulty similar to the legendary Worlds in Sallanches in 1980.

Then there was the high drama of the closing laps, as Abraham Olano attacked from a group of less than a dozen riders, only to puncture and race home seconds ahead of his chasers on a deflated back wheel. It was nailbiting stuff of the most unpredictable variety, the race’s hardness highlighted by the fact only 20 riders - mudspattered and exhausted - finished. Last but not least, the controversy about why Olano, not Spanish team leader Miguel Indurain, had managed to win when Indurain was clearly the race’s strongest rider, rumbled on and on afterwards for months - except in Spain that is, where asking Olano if he "really should have won the 1995 Worlds” was a question that plagued the Basque for the rest of his career.

On paper, the outcome of the amateur World Championships race, held on the same high-altitude circuit in Duitama the day before, had been set to be equally uncertain. And certainly on television, the racing looked to be just as unpredictable - something that's part of the great appeal of the U-23 World’s events, even now.

The elite men's podium at the Worlds in 1995: Miguel Indurain, Abraham Olano and Marco Pantani

However, in the mind of the eventual amateur World Championships winner, Danny Nelissen, victory was the only possible outcome. In fact, his conviction that he was going to cross the line in first place was so great that 24 hours previously he had told his uncle Jean - a cycling commentator for Dutch state television in the Colombia Worlds - to get the champagne ready for celebrating, “because I will be solo at the finish and World Champion.”

Part of the reason for Nelissen’s almost outrageously high sense of self-confidence was because, he says, “I had the best preparation, I had the best bike, I had all the best data, I felt really great, and so it was going to happen. And it did happen.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

To judge from Nelissen’s explanations, that word ‘preparation’ was not, for once, a euphemism for doping. Indeed when in 2013 he confessed to using banned drugs at Rabobank in 1996-7, Nelissen insisted he only took them as a professional, not as an amateur.

Rather, Nelissen calls his win a "data-driven victory," and that comment alone makes his win worth revisiting, 22 years on.

After all, this was an era of cycling when technology, aerodynamics and data analysis were all either in their infancy or were used only patchily. Chris Boardman, in particular, was making waves on the aerodynamics front in the mid 1990s, and as Boardman has often observed, even minimal advances in these areas were so little known they could net major rewards. But at that time SRMs, which Nelissen says played a huge part in his success in Duitama, were still only infrequently used.

Together with Greg LeMond in 1993-4 and Jonathan Vaughters, who turned pro in 1994, “the only other guys I can think of that had them and knew what they could do,” Nelissen was a kind of pioneer for SRMs, thanks to the three of them having the same trainer, Adrie Van Diemen. LeMond, for one, would later lament that he had not started using SRMs earlier in his career. Indeed, in a sport as ‘old-school’ as cycling, advances like the SRMs, first used in 1991 by the German National squad, but by few others, were often viewed with a large dollop of cynicism. “Everybody was laughing about them. Other riders used to ask me, ‘can you fuck with them too?’” Nelissen recalls with a chuckle.

“And I’d tell them, ‘not yet, but soon.” Winning though, that wasn’t out of the question. Or as Nelissen puts it, “I was laughing to myself, because I knew what my advantages, by having them, would be over the rest.”

Pacing makes perfect

In terms of Duitama, Nelissen hadn’t exactly picked a straightforward target to win. As the last ever amateur World Championships before the category was switched to U-23, the UCI seemed determined that the 1995 race would go out with a bang. The field that year was one of the bigger ones - 234 riders, 100 more than the previous year and from 60 nations - which meant controlling the race would be a near impossibility. Then on a 17.7 kilometre circuit at 2,500 metres up with 315 metres of climbing the challenges in terms of terrain were almost equally hard.

Nelissen was dropped every time the race tackled the hardest part of the course, “but that was the tactic. It was a horrible, hard climb, and I’d gone out to Colombia five days beforehand, so I said to my trainer, there was no way I was going to get over it.”

To find a solution, “he told me to ride up the climb in five particular ways during training - sprinting, with tempo, full gas - all that different ways and from all those we would analyse the data. When that data came through it turned out that riding tempo gave me the fastest result [time].”

“So in my head, I had to skip all the things I had learned as a rider from when I was ten, like not to go with attacks on the climb, even when I felt strong enough to do so. I was always [telling myself] ‘keep quiet, keep your own tempo, you are much faster like that, than when you go with the attacks.”

“Each time we went over the climb, I’d ease back, and I saw the tactic worked.”

When he caught up each time with the leading break on the descent that followed, “I began to believe in it. So I kept that going until the penultimate lap.”

The weather added to the toughness, though “it was really hot,” adds Nelissen.

“I had a jersey which only had a small zipper, so I took a long jersey, which had a long zipper, and cut off the sleeves to race with them. Plus being at altitude that made it even harder, to give you an idea, we were 400 metres higher than the summit of the Tourmalet. And that was before we did the climb. Racing there was crazy.”

Some teams had considerable logistical difficulties or financial ones. The British team in this pre-National Lottery funding era, could not afford the flights to send all of their staff.

Nelissen had had an advantage there too, because unlike in some amateur line-ups where, with professional contracts luring them on, the power struggles can be vicious, the Dutch squad was very well organised and peaceful.

“We’d been training together for eight weeks in Colorado and we had time to sort things out. I was the leader, and I don’t recollect any arguments in the whole time we were there, and nobody made any mistakes. It was a really good team.”

Nelissen was also able to exploit the fact that it was the year before the Olympic Games to ensure the Dutch Federation invested heavily in the amateur team. “Qualification for Atlanta was only automatic to countries with finishers in the top 15, so when they told me that, I told them that winning a race in Colombia or finishing in the top 10 wasn’t going to happen just like that. You needed a good trainer, a long period of altitude training, and a good team. So they paid for everything, the whole Dutch amateur team went to Colorado, as well as the track team and the women, and some of the pros, too.”

Colorado proved a popular choice. “The Swiss were there, the Americans, the Belgians, the French,” although the presence of five times Tour winner Miguel Indurain logically meant that the Spanish squad stood out from the rest.

“It was really funny. There were some cycling shops in the area and there were all these big names out there, so they thought ‘hey, let’s organise a race.’ So without any start money, these shops had Indurain and [Spanish rider Santiago] Blanco and all of these people lining up on the start line.”

Training at altitude was a huge advantage, he said. “In the 31 days I spent in Colorado, I trained approximately at 40 percent of my power that I was turning out in Holland at sea level. With the data I had you could see that you needed less training because of the altitude. When you saw the other guys with a heart rate monitor, they couldn’t measure all the other parameters to really define what they were doing. Adrie and I had that advantage, and I could send my files through Compuserve and he could analyse and email me back what to do and what not to do. So there were no broken lines of communication.”

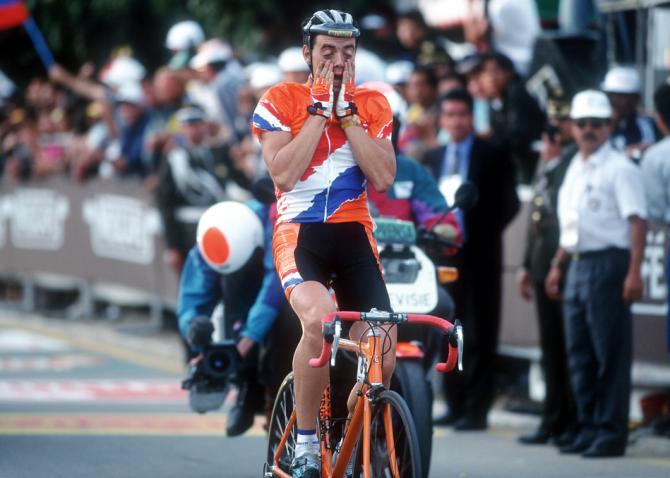

Danny Nelissen becomes the champion of the world

Nelissen noticed that such a prolonged period of altitude training was not entirely beneficial though. “You have less oxygen for the muscles so your output and wattage will also go down. We’d already figured that out because of the data so we ordered 6,000 litres of oxygen for my hotel room” - roughly 10 days worth of consumption - “and I did special power training on the rollers there to keep my muscles strong enough at altitude. Adrie had the plan, but it was all proven by data. Then we went to Colombia one week before. Then we did one training ride and the rest was resting and racing.”

Not that Colombia was apt for the nervous. “We had military transports at some point because we were travelling through FARC guerrilla-controlled territory and we had to go training with soldiers accompanying us. They had AK-47s on their backs as they rode along on their motorbikes.”

Once you got over that, though, Nelissen says he was very taken with the country. “There was something special about racing in Colombia. I’d never raced in South America, but I loved the country, loved the people, it was a really nice experience. Not because I was World Champion, just being there was good.”

Nelissen took huge precautions not to go down with food poisoning. For the entire week he was there “I didn’t eat meat, or the fish, or the spaghetti or the rice or the bread… just fruit, mangos and stuff, only bottled water, because of the risk of getting ill.”

He did not have to look that far to see what the consequences could be: “The rest of my team, they had ravioli one day and they were all sick.”

On the plus side, his bike was state-of-the-art with a “carbon monocoque with full carbon wheels, based on the one Chris Boardman had used in the Hour Record [in 1994]. So that position I could use on that bike added to my advantages.”

Scattered all over the Andes

But at the end of the day, bikes and team back up and preparation and precautions will only get you so far, and when the flag dropped it was all down to Nelissen’s strategies, team support, and individual strength. The race itself had shattered early on, more as a result of the hardness of the course than any particular concerted attacks. But there was a discernable wave of stronger riders at the front.

Italy’s Marco Fincato went for a long-distance move, covering five laps from the start alone, and for some time his closest pursuers include Nelissen, Britain’s Matt Stephens and Colombian Jose Luis Vanegas, another strong South American talent.

“Matt and I were dropped in a race before the Worlds, the Tour of Wallonie,” Nelissen recalls, “and we were sitting together in the bus [broom wagon] and he was ill. So we got chatting - ‘how are you doing, are you going to the World’s, oh, I’ll see you there.’ And the next time we met up was in the winning break somewhere in the middle of Colombia!”

Present, too, at the pointy of the action, was Pedro Alvaro Rodriguez, aka ‘the Eagle of Tulcan’ a semi-professional and expert climber from Ecuador who had won his national Tour on multiple occasions as well as stages of the Vuelta a Colombia.

The Italians looked to be the strongest collectively: they had several riders, including the late Valentino Fois and Daniele Sgnaolin, briefly later a pro with Roslotto, in a third chasing group behind Fincato, and the Nelissen, Stephens, Vanegas move. Nicola Bo Larsen, later a transition stage winner in the 1996 Giro after a long two-up break and a team-mate of Nelissen’s at Team Jack&Jones in 1999, was also close behind. Most of the rest of the field were long out of the running, thanks to the toughness of the course, and the high average speed of 36kph - just a couple of kph slower than the professionals the following day. Or as one British commentator memorably put it in his report on the race, “ they are scattered all over the Andes.”

Team support crumbled early on, as the race disintegrated. “We” - Nelissen, Stephens, and Vanegas - “went away in the second lap, and there was no radio communication so we didn’t know anything.”

“We had to race on instinct.” But as they passed more and more lapped riders in the massive field, Nelissen says it was clear they were not going to miss out on some kind of success. “I knew that the one who was going to be World Champion was going to be that group. I wasn’t watching anybody in particular because I didn’t really know anybody, I’d been a professional before” - from 1990 - 1994 , dropping down a category because of heart problems [Ed.] - “and I hadn’t raced much as an amateur because I had turned pro so young. I knew Matt, obviously, and I knew Bo Larsen, but I’d never raced against the Italians before.”

However, he felt what he had learned as a professional outweighed those disadvantages. “Tactically, you were operating on a different level, you were more experienced and more advanced than the rest, so it was quite unfair. But those were the rules at the time, you could do that.”

After that, after the long build up, the preparation and the diet and all the other factors, Nelissen’s final break for the line took place just over a lap from the line. “I saw a moment that the guys were going to brake for a corner, and I wanted to go somewhere that wasn’t entirely expected. So after 250 metres of a descent, I went for it.” And, as he had predicted, when he crossed the line in Duitama and raised his arms as cycling’s last ever amateur World Champion, Nelissen finished alone.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.