Cavendish fights back

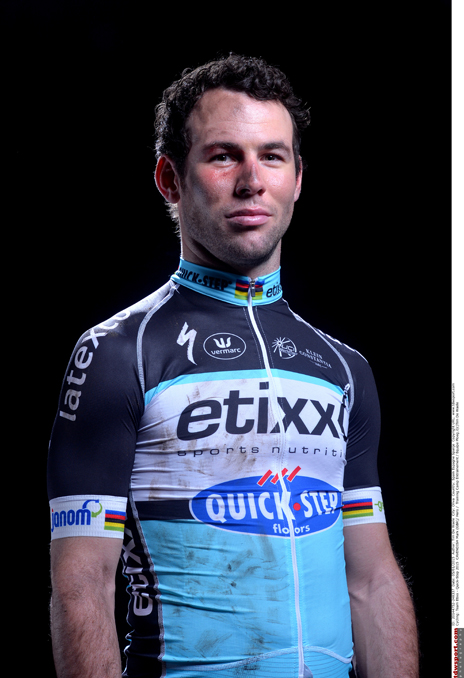

Etixx-Quickstep sprinter tells Procycling he's hungrier than ever

The following feature appeared in the April edition of Procycling.

When he turns 30 in May, Mark Cavendish will already be, by most estimates, the finest sprinter that professional cycling has ever seen. The question on the eve of the 2015 season was whether the Manxman was also nearing the end of the road.

Even in a career that Mark Cavendish conducts like a religious crusade, there have been moments when both the Manxman and the cycling Gods have seemed to bow before the enormity of their undertaking.

When he turned pro with T-Mobile in January 2007, the team's coach, Sebastian Weber, took one look at the doughboy's physique, then at his power numbers and scoffed; Cavendish would never amount to anything. A team-mate, the Spaniard Vicente Reynes, assumed in 2008 that he must be a friend of the sponsors. Both Weber and Reynes were wrong - happily, spectacularly so - but the sense that Cavendish could only stick one finger up to history, logic and physiology for so long, that sooner or later security would step in and remove the interloper, has persisted even as records and rivals have fallen.

So for Cavendish, a whiff of scepticism, even pre-emptive Schadenfreude among reporters who have gathered to meet him at Etixx-Quickstep's Janunary training camp in Calpe is nothing new. He may not trawl forums or even Twitter as he once did but he knows the wolves can smell blood. Never mind that he ended the 2014 season with twelve victories. He also failed to win a grand tour stage for the first time since 2008 and extended an unbroken, winless run of sprints against Marcel Kittel that stretches back to 2011.

A poolside Q&A session with a dozen or so international journalists therefore takes on the mood and tone of a stand-off. Above the glares, monosyllables and uneasy silences, the only question that really matters hangs in the air, unbroached: is Mark Cavendish, the mongrel prodigy once feted as the greatest and fastest sprinter of all time, really past it at age twenty-nine-and-three-quarters?

Any other line of enquiry will be mere posturing - and yet no one dares to go there. Instead, after ten thoroughly uncomfortable minutes for all concerned, a collective mumble of defeat signifies that everyone's work here is done. If Cavendish himself thinks that he will need all the sympathy the press can give him over the next few years, a soft landing to cushion his descent back into the sprinting rank and file, it is not in Calpe that his charm offensive will begin.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

A few minutes and a few swigs of espresso later, in the relative calm of the hotel bar, he is finally serene. This has been his best winter for several years, perhaps since 2008-2009. Cobwebs of blue vein already protrude from under tanned skin. "I'm going pretty well," is all he really needs to say.

Cavendish's manager, Simon Bayliff, sits a few yards away, listening in. Bayliff is here today mainly as his client's chaperone, but he too will be seeking important answers over the coming weeks and months. Cavendish, as the whole of cycling knows, is out of contract. And the difference between a good start to the 2015 season and a bad one could end up being computed in millions of Euros.

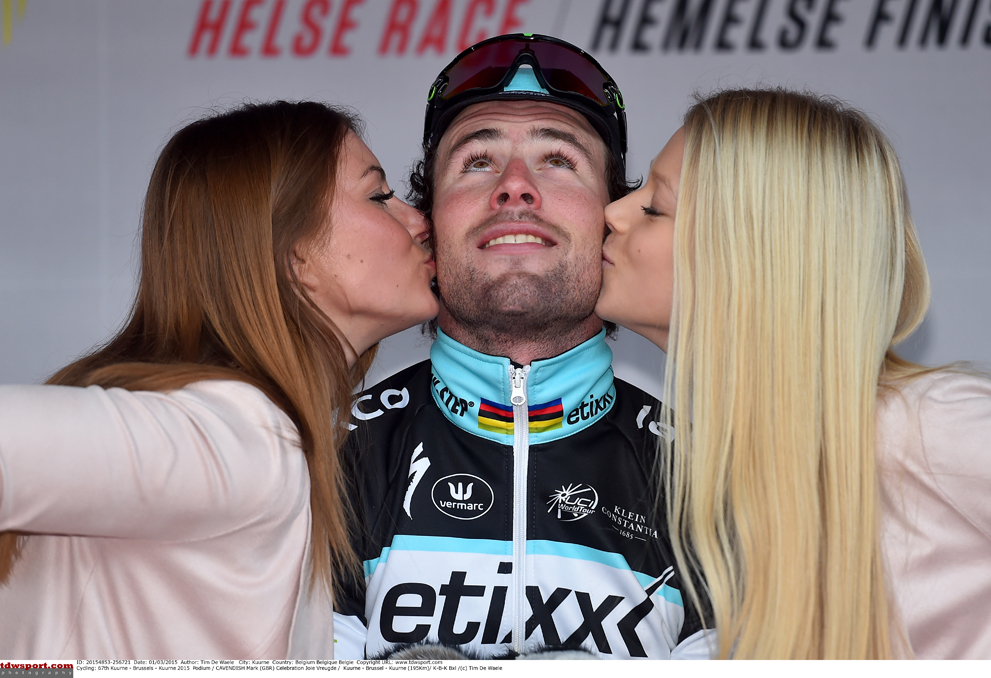

Back to winning ways in 2015

The driving force behind the "Highroad-ification" of Lefevere's team is undoubtedly Aldag. After the American outfit's demise at the end of 2011, the former T-Mobile rider spent a year at the World Triathlon Corporation before taking up a role as a technical link-man between Specialized and what was formerly Omega Pharma-Quickstep in 2013. His responsibilities then broadened in 2014 as he became the team's Sport and Development Manager. Central tenets of the Highroad recipe are increasingly evident: a focus on scouting, exemplified by the recruitment this year of former Mapei, Lampre and Saunier Duval directeur sportif Matxin Fernandez for solely that purpose; a cosmopolitan roster - a factor that both Aldag and the former Highroad owner Bob Stapleton considered vital for avoiding cliques; a passion for developing young riders; a lust for new technology.

While acknowledging Aldag's input - and that of fellow Highroad survivor, the directeur sportif Brian Holm - Lefevere assures Procycling that another man, Zdeněk Bakala, deserves even more credit for Etixx-Quickstep's transformation. The Czech billionaire purchased a 70% stake in Lefevere's team in 2010, immediately positioning them among cycling's big spenders. When we remind Lefevere of Cavendish’s gripes in his first season, he contends that it has taken time to give the team a new identity and for existing contracts to run their course. "It's nice to eat at a Michelin three-star restaurant….but you'd better have a fat wallet," he smirks.

Crashing out of the 2014 Tour de France

He goes on: "You can't go into battle on all fronts with 10 million euros when Sky have 30 million. But when Mr Bakala came onboard, I made a switch in my head. Suddenly I could afford a team that was winning races from January to October. Then I brought the right people in to achieve that - the Cavendishes, but also the Aldags, the Brian Holms…"

Lefevere is broadly happy with Cavendish's first two-and-a-bit seasons with the team. The sprinter's 36 victories in that time have received curiously little recognition. For two reasons: one, the stratospheric standards to which he accustomed us at Highroad; and, two, Kittel's recent superiority on the stage that matters most in sprinting, the Tour de France.

It is clear, though, that Cavendish still has something to prove to his Etixx team boss - certainly if he wants to maintain his earnings at their current level. Cavendish tells us in Calpe that he would "love to sign for another three years". And Lefevere would apparently like to have him - with certain provisos, at a certain price. "There's no point talking now," Lefevere says curtly. "We'll do one assessment after Ghent-Wevelgem, then another one after the Tour de France - because that's Mark's bread and butter. If Kittel beats him five times, the story changes a little. Maybe then he'll have to accept my offer… Everyone here likes Mark. He likes his team-mates, he's generous with them, gives them presents…but it's what he does on the road that matters. I like champions, not pseudo-champions."

There is part of Cavendish that perhaps resents having to prove himself, after so many laurels, so much success. On the other hand, he has seen enough in professional cycling to know that it can be a cruel world, one which values sentiment and loyalty less than your last sprint finish. He learned this the hard way at Highroad, where Stapleton held him to a long-term contract that he had signed on a rest-day at the 2008 Tour, on his own, without any advice from an agent. Stapleton's refusal to give him a pay-rise when Cavendish doubled, tripled and quadrupled his market value over the next three seasons eventually led to a complete breakdown in their relationship. One could also argue that it precipitated the end of Highroad.

That, though, is all in the past. Cavendish and his entourage know that negotiations with Lefevere will look after themselves if he keeps on winning. All parties hoped that crashing out of last year's Tour on stage one to Harrogate would be a kind of wake-up call - and so it has proved. "It made me realise that I really don't want to miss the Tour again," Cavendish says in Spain, reflecting on a fall that he claims to have watched back "only a couple of times" before banishing from his memory. The resulting injuries could quite easily have kept him out of action for the remainder of 2014. If he returned to racing at the Tour de l'Ain in August, then won twice at the Tour du Poitou Charentes a fortnight later, it was partly to show Lefevere his mettle, partly to lay the groundwork for a fast start in 2015.

He also spoke then of a gradual shift that wasn't physiological but psychological in nature: "More sprinters as they get older think of the consequences if they crash - they won't do certain dangerous moves. Most sprinters lose that as they get older. It's very, very rare to have this thing...like, a lot of sprinters - Tom Boonen, Thor Hushovd - they're just strong if they get a good lead-out. But me and Robbie McEwen aren't strong - we can't push ourselves in the wind. We have to fight and use other things, other factors, which means using the best factors to get the best result. That means jumping trains, leaving your own lead-out train. Sometimes it goes wrong, but if you keep changing, most of the time it'll go right."

Over the past three seasons, as Kittel has slowly encroached on and overturned Cavendish's dominance, it has been tempting to wonder how much precisely these phenomena have diminished Cavendish. He appears to entertain that possibility when allowing himself to imagine that the German is now simply unassailable, sighing deeply, and philosophising about "the cycle of life". A minute later, though, he is responding to questions about his German rival with a terseness born not out of genuine dislike but at least some needle. And if there was any doubt about how much it all still means to him, how much he still wants it all his way, we only have to listen to his scathing assessment of Giant-Shimano lead-out man Tom Veelers.

During last year's Tour de France, Dutch broadsheet Algemeen Dagblad hailed Veelers as "the best lead-out man in the world". Ever since a crash in the closing metres of the Tour stage to Saint Malo in 2013, Cavendish has held and vocally expounded a different view.

"Kittel, I quite like, but Veelers…" he bridles. "He doesn't even lead Kittel out any more. He sits on his wheel; he's a sweeper. Last year he grabbed Renshaw's arm on the Champs Elysées because Mark was trying to get on Kittel's wheel. He thinks he's got a right to be there… I'm never going to get over St Malo."

Hearing this, most Cavendish fans should feel reassured. The same bloody-mindedness, the same belligerence that has always fuelled his ranting and raving is, after all, at least a close relative of the passion that can sledgehammer through a pain barrier. At Team Sky, perusing his performance data, Tim Kerrison couldn't even believe that Cavendish was capable of finishing a Tour de France. Rob Hayles, his World Championship-winning former madison partner and until recently his motorpacer in training, makes a similar observation. "His stubbornness is part of what makes him so good. When you see what he does in training, then set it against what he does in races, you can't believe it…"

Back in the High Road days with former teammate Bradley Wiggins

But can this last? Are we still to believe what Cavendish said back in 2008, that "passion is the core of everything, and science is no substitute at all"?

Or, conversely, should we worry that the Manx Missile is too quick to pooh-pooh some of the methodologies, some of the Vorsprung durch Technik now propelling Kittel and Giant-Alpecin? In matters of equipment, he remains as discerning and demanding as anyone in the bunch, but his training can still seem remarkably homespun and ad hoc. Where Kittel and his coach Adriaan Helmantel have dabbled extensively with sprint-training at altitude and even drills on the Zandvoort motor-racing circuit, Cavendish doesn't currently have a coach and doesn't follow structured training plans. At an Etixx training camp this winter, he deigned to undergo a VO2 max text for the first time in years…only to climb off halfway through. “I ride a bike like no one else rides a bike. When I ride a stationary bike, I'm moving it so it's not efficient…The test is pointless," he tells us by way of an excuse in Spain.

This would no doubt cause some acquaintances to roll their eyes. "He's always right until it's too late," remarks one. Lefevere, fortunately, doesn't seem to mind: "Tom Boonen isn't a fanatic of training or tests either. I'm only interested in what happens in the races, not training."

Cavendish says that conversations with his former guru, Sky race coach Rod Ellingworth, now revolve around their respective children - partly because of a strict new UCI rule that forces riders to log all contact with staff from other teams. After four defeats to Kittel at the 2013 Tour, he conceded that he perhaps needed to experiment with more specific sprint work - but he is still doing too little for some tastes.

"He perhaps did a bit more of that in 2014 than I'd seen him do before - just throwing in a sprint at the end of rides," says Hayles. "I know that now and again he'll look at his peak powers, and he gets annoyed if his power meter isn't working, but that's about it. I don't know what he does when he's away with the team. He also simply can’t do the same training that he did eight years ago, with the lifestyle and the responsibilities that he has now. The season he spent at Sky, it was frightening how much stuff he had to do off the bike. That may be something Kittel is experiencing now."

Some of which might sound alarming…if Cavendish hadn't enjoyed the rip-roaring start to the season that he promised last autumn. One tweak that he did make to his pre-season preparations, riding Six Days in Ghent and Zurich, appeared to have had the desired effect of reviving old muscle memory from his track days. "I feel more natural on the track than on the road, if anything," he had told us in Calpe. Commanding wins in San Luis, two stages and the general classification at the Dubai Tour, then at the Clásica de Almeria, suggested that a return to the boards had also brought noteworthy gains on tarmac.

Over the next few months, though, we may discover that the most important changes have occurred in his team - or at least the way Cavendish uses it. "When he arrived here, he didn't know Iljo Keisse, didn't know Julien Vermote, and now they're the kind of guys who can be really useful to him," Lefevere says. Etixx's sprint division has also been strengthened, Cavendish and Lefevere would argue, by the arrival of Cavendish's sometime Italian training partner, Fabio Sabatini. And by the departures of Alessandro Petacchi and Geert Steegmans, both square pegs in round holes during the 2013 and 2014 seasons.

Most crucially, though, he is now established enough at Etixx to impose his choices and personality. "Last year I don't think he was confident enough in himself to be really assertive. He kept fairly quiet. This year that should change, and the team could become his big advantage," says Hayles.

Most experts would certainly like to see a more decisive, more committed Etixx train in the closing kilometres of races. Or, to be precise, they would like to see a more sudden, unerring explosion into action at around the two-kilometre-to-go mark, much more like Giant-Alpecin's. When Cavendish tells us why sprinting as he did in his 2007 neo-pro season, buzzing from from wheel to wheel like a bee between flowers, is "impossible now because there are so many trains", he is also unwittingly explaining why the steady crescendo of his old Highroad chorus-line can no longer work. There have, it's true, been signs over the past few months and weeks that Etixx are finally beginning to move with the times.

In a more general sense, Cavendish really has no option: his choices are evolution or oblivion. Moreover, his is an ambition that has always borne more similarities to need than desire. The next few months and years will prove whether that remains the case, or whether maturity and family-life have brought a different set of priorities.

For now, smiling, he says that he craves not "just one last cherry on the cake, but a bag of cherries - then another cake." That would presumably cover another Milan-Sanremo victory, the nine Tour de France stages he requires to equal Eddy Merckx's record, a second rainbow jersey in Qatar in 2016, and ultimate triumph in the war with Kittel. If it isn't already, the debate about who is the greatest sprinter of all time would then be settled.

As it is, Cavendish finds himself a month short of his 30th birthday, joking about his grey hairs and impending breakdown while also meditating bleakly about changes in the peloton in his eight seasons as a pro. "I was brash when I was younger but I still had respect for the riders who had achieved something. There's no gentleman's respect anymore."

At moments like these, Cavendish can sound weary, a different beast from the thrusting tyro who once brought to mind something that Oasis' Noel Gallagher said about his brother, Liam: "He's like a man with a fork in a world of soup."

Such was that young man's hunger and thirst that he always found a way. It follows that if he hasn't lost those, it's far too early to stick a fork in Mark Cavendish.