A beginner’s guide to the Ardennes

From Amstel Gold to Liege-Bastogne-Liege

The finale of Paris-Roubaix brings a change of focus in the Spring Classics. After five weeks of pavé and bergs that are largely the preserve of the peloton's most potent pedal-pounders, mid-April brings out much slighter figures tempted by the longer climbs of the Limburg region in southern Holland and the Belgian Ardennes. So it's goodbye to Alexander Kristoff and John Degenkolb, and welcome to Alejandro Valverde, Dan Martin and, for one race at least, Chris Froome.

The Ardennes Classics comprise three big events: the Amstel Gold Race, Flèche Wallonne and Liège-Bastogne-Liège. First up is Amstel Gold, which is branded an Ardennes Classic because of its location just across the border from that region and the amount of climbing that features on the route. The Dutch race starts in Maastricht and has as its focus the Cauberg, which climbs for a kilometre out of the town of Valkenburg and is tackled three times.

A look at the Amstel race map suggests it has a touch of the Tour of Flanders about it as it twists and turns in labyrinthine fashion. But with a staggering 32 climbs, ranging between 500 metres and 4.3km in length, and all manner of Dutch road furniture to deal with, it is a very different kind of test to Flanders. Most of those climbs, which average up to 9% but are generally around 5-6%, are packed into the second half of the race, when the peloton is steadily whittled down.

Between 2003 and 2012, the finish was located at the top of the Cauberg, favouring puncheurs of the ilk of Philippe Gilbert. However, since then Amstel has followed the example of Valkenburg's 2012 World Championships by moving the line 1.8km beyond the crest of this hill. This move hasn't fazed Gilbert, who not only won that 2012 world title but also claimed a third Amstel success last year after powering clear of his rivals on the Cauberg and holding off their attempts to get back on terms over the 1800-metre finishing straight.

Amstel Gold Race 1987: Joop Zoetemelk is remembered more for his success in stage races than one-day events, but the Dutchman did manage to win the world title and, in the very final year of his long career, he finally captured his country's biggest race. By then 40, Zoetemelk was one of five riders who went clear going over the Cauberg, which was then 15km from the finish in Meersen. The veteran was with compatriots Steven Rooks and Teun van Vliet (no relation of current Amstel race director and ex-pro Leo), little-known British pro Malcolm Elliott and Frenchman Bruno Cornillet. Just about all the trio of Dutch riders knew about Elliott was that he was very quick in a sprint, so rather than duel with each other and set up Britain's first Amstel victory, they joined forces. Elliott countered their attacks, but didn't have the legs to chase when Zoetemelk slipped clear 3km from home.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Four days on from Amstel, Flèche Wallonne also includes an iconic ascent that is tackled three times in the men's and twice in the women's, which takes place on the same day. Rising 121 metres in 1.3km, the Mur de Huy is an intriguing test, and not only because the finish comes at the top of the third ascent. It favours both pure climbers like Purito Rodríguez and Alberto Contador, and puncheurs such as Gilbert and Dutchman Bauke Mollema.

Riders of both these types have the rapid acceleration needed to get a gap, but the Mur's super steep ramps that reach 25% in parts make it especially tough to maintain an all-out effort. Consequently, judging the right moment to deliver that acceleration is vital.

In recent years, Spanish riders have dominated, Rodríguez, Dani Moreno and Alejandro Valverde claiming the last three editions, the latter setting the fastest time ever for the climb when he took his first Flèche success in 2014. This year's edition has added significance, as the second stage of the Tour de France will finish atop the Mur. This has enticed Team Sky's Chris Froome into carrying out some competitive reconnaissance by making his first appearance in the race since 2010.

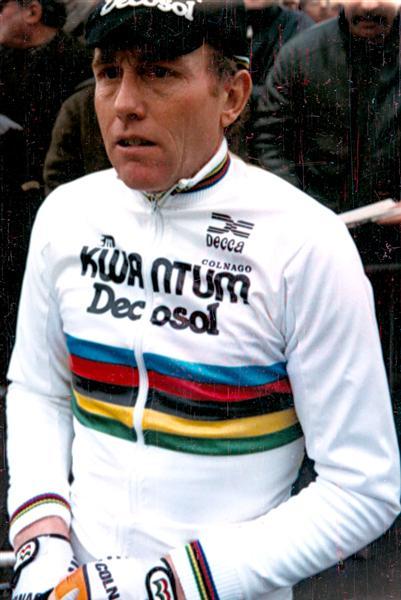

Flèche Wallonne 1985: Prior to Philippe Gilbert, the icon of Walloon cycling was Claude Criquielion. Claudy, as he was known to his hosts of fans, won the world title in 1984 and, consequently, lined up in the rainbow jersey for the Ardennes Classics the following spring. Beaten by Moreno Argentin in Liège-Bastogne-Liège, a race that always eluded him, "Criq" turned the tables on the Italian in Flèche, dominating the latter part of the race to the extent that his ascent of the Mur de Huy became almost a victory parade in front of thousands of ecstatic Walloons. He won the title again in 1989 and went on to become a directeur sportif following his retirement. He died in February after suffering a stroke, and will be remembered by ASO prior to the start of this year's race.

The Spring Classics campaign concludes with what many pros regard as the toughest one-day race on the calendar. First run in 1892, Liège-Bastogne-Liège, the oldest of the sport's five Monuments, is known as La Doyenne. Like its sister race, Flèche Wallonne, it is run by Tour organisers ASO and offers a test that tempts both puncheurs and climbers. Australia's Simon Gerrans, one of the former group, won it last year, succeeding Irish climber Dan Martin.

Liège combines a mixture of shortish, but very steep ascents such as the Stockeu, La Redoute, Roche-aux-Faucons and the Côte de Saint-Nicolas, with longer climbs of up to 4km, notably the Haute Levée, Côte du Rosier and Côte de la Vecquée. But little of the run back northwards to Liège from Bastogne is flat, as the route dips in and out of steep-sided and heavily forested valleys.

The plateaux above these valleys are home to Belgium’s ski industry, which gives an indication of how poor the conditions can get in this area. For an idea of just how bad it can get, check out the footage of Bernard Hinault’s epic ride to victory through snow and freezing conditions in 1980. Arguably the most renowned race in the history of the Classics, it left Hinault with a permanent reminder of his second Liège success. Even now, two of his fingers go numb when the temperature drops towards freezing.

In recent years, late breakaways by lone riders and small groups, which often used to decide Liège, have been far less frequent. Indeed, some observers have suggested that ASO's toughening up of the final 20km has ensured that riders now hold back for so long that the race has become boring. Lotto-Jumbo DS Merrijn Zeeman says he can see from his riders' performance data that Liège is still a very hard race, but understands why some may have come to this point of view.

"I think there are two reasons why it might appear boring," says Zeeman. "Firstly, the loop after the Haute Levée used to feature three climbs in a row. Now there's more time to recover on good roads, so there are still a lot of riders who are fresh before La Redoute. The final is also harder now with the addition of La Roche-aux-Faucons.

"The second thing is that pro cycling is changing so much that you have 18 strong WorldTour teams. Every team has a leader with his helpers. So, for example, when Philippe Gilbert attacks on a climb there are always a lot of helpers around to bring back a leader. There's more depth to the competition, more and more favourites, better strategy, better nutrition, better training, so the level is going up, but there aren't such great differences between the teams. There's tighter control of races because of that."

Local hero Gilbert has made a second Liège win one of his primary targets of the season and there would be no more popular winner. But the extent of his task is underlined by the fact that the three riders who finished on Liège’s podium in 2014 – Simon Gerrans, Alejandro Valverde and Michal Kwiatkowski – also filled the podium at last year's World Championships.

Liège-Bastogne-Liège 1980: 1976 Tour de France winner Lucien Van Impe was never a big fan of one-day races and often used to tell his wife, Rita, to be waiting in the car at a pre-agreed point where he could quit. On this freezing, snow-blown morning, Van Impe told her he would be climbing off right on the edge of Liège. Within a few dozen kilometres, two-thirds of the 174-strong field had followed Van Impe's example, and Bernard Hinault would have joined them but for a brief break in the weather and the encouragement of his Renault teammate Maurice Le Guilloux. Although the snow returned, Hinault pressed on. With 100km to race, Renault DS Cyrille Guimard went up alongside Hinault and told him to take off his jacket. "The race is starting now," Guimard told him. With teeth chattering, Hinault upped his pace to keep warm. On the Haute Levée, he turned to usher other riders through to find he'd ridden everyone off his wheel. Eighty kilometres later, Hinault rode in nine minutes clear and asked his teammates to thaw him out in a cold bath. A mere 21 riders finished.

Peter Cossins is the author of The Monuments: The Grit and the Glory of Cycling's Greatest One-Day Races (Bloomsbury)

Peter Cossins has written about professional cycling since 1993 and is a contributing editor to Procycling. He is the author of The Monuments: The Grit and the Glory of Cycling's Greatest One-Day Races (Bloomsbury, March 2014) and has translated Christophe Bassons' autobiography, A Clean Break (Bloomsbury, July 2014).