Cheers from Benin!

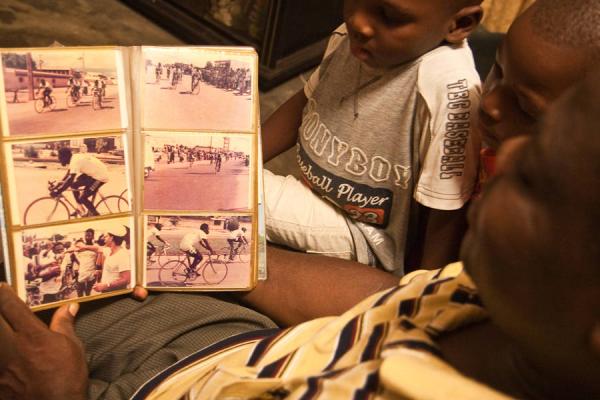

The great Saka and the base of modern day bike racing in Benin

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Benin is a small nation in West Africa, a narrow strip of land west of Nigeria. As the origin of Voodoo beliefs, Benin is culturally rich but economically underdeveloped. Most Beninese subsist on agriculture and fishing. While many African nations struggle with conflict, Benin exemplifies peace and democracy with 56 ethnicities sharing limited resources in a country the size of Pennsylvania.

As a former racer, I was intrigued one day by the sight of a young cyclist dodging potholes and mopeds on the congested streets of the capital. I had to learn more. I soon discovered that the Beninese Cycling Federation fields a team of athletes in competition throughout Africa. In a nation where funds are scarce and smooth roads are scarcer, what does it take to race bikes here? This blog will explore the nitty-gritty of cycling in Benin and highlight the athletes who persist against remarkable odds.

History of Cycling in West Africa

Africa may be the cradle of humankind, but the cradle of bicyclekind certainly lies in Europe. French missionaries and colonialists introduced bicycles to Benin in the early 1900’s. Continuing their pastimes from home, the missionaries organized races and invited locals to participate. By the time Benin gained independence in 1960, a cycling subculture had developed and local athletes like Bienvenue Zah and Christophe Alladaye dominated the dirt roads of Benin.

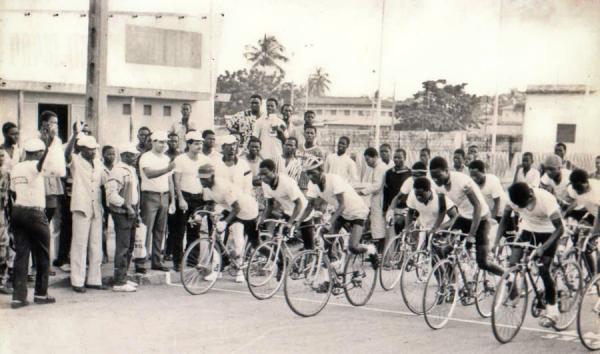

The Beninese Cycling Federation developed in the 1970’s as Benin emulated the Soviet Olympic athletics program. Clubs were formed in larger cities to recruit local talent. With regional competitions drawing athletes from neighboring Togo, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Nigeria, a crop of talented athletes emerged. These individuals would sow the seeds of a cycling culture that would eventually produce international caliber athletes.

The Great Saka

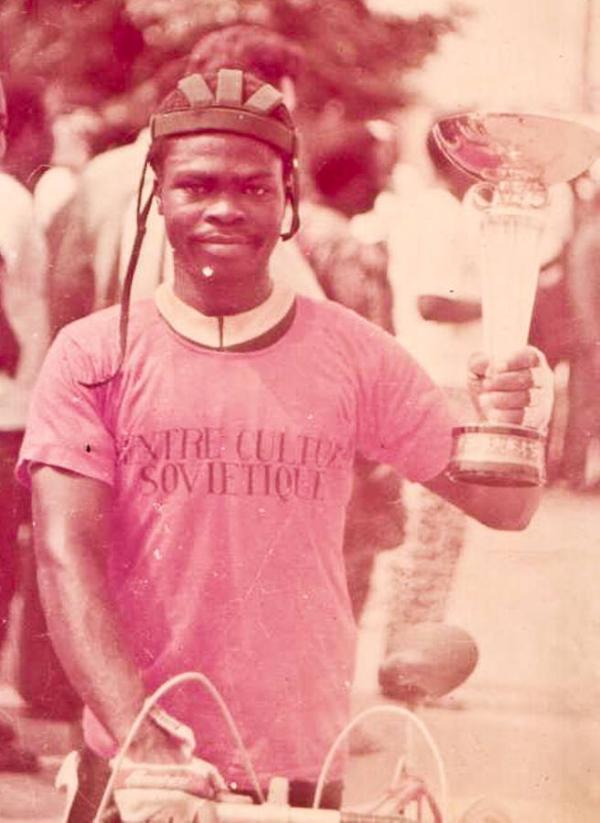

In 1981 a youngster by the name of Mustafa Saka entered the scene. Within three years, he claimed the national championship. Much like Eddie Merckx in his prime, Saka dominated cycling in the region for nearly a decade. Why was Saka so good? He paid compulsive attention to detail.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

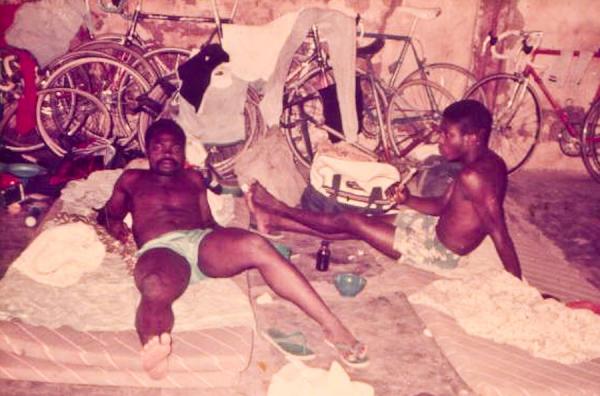

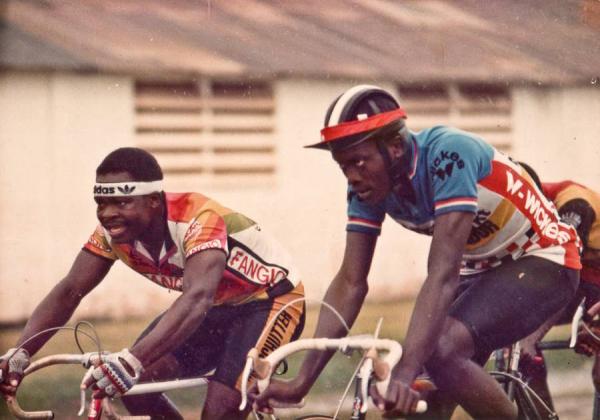

He studied the pages of the French magazine, Le Mirroire du Cyclisme, to learn the nuances of European race tactics and training. Saka become Benin’s first strategic racer. He conserved energy, and emerged 200 meters from the line to claim sprint victories. On regular training rides to Lomé (the capital of Togo), Saka searched the port for used frames, wheels, narrow tires, and caged pedals.

In his spare time, he scrounged the chaotic markets for used cycling clothing. Amidst the bins of second-hand European clothes, Saka found lycra shorts and neon jerseys. Vendors were happy to sell him these peculiar garments for mere pennies, and Saka resold this modern equipment to his competitors.

Saka also pioneered the idea of conserving good equipment for race day, saving his smoothest tires and least patchy tubes for competition.

Francis Ducreux

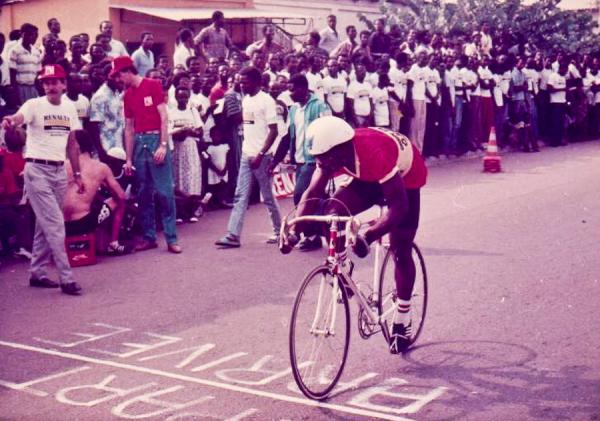

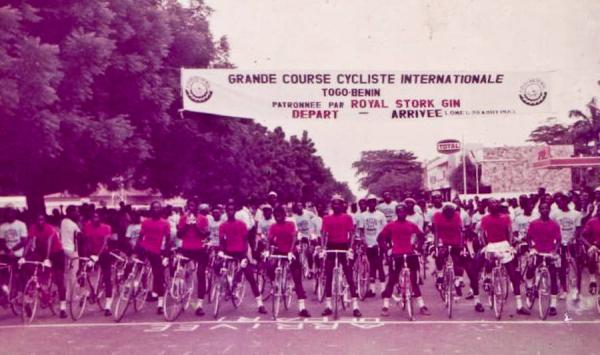

The emergence of Saka as Benin’s premier cyclist coincided with the arrival of Frenchman Francis Ducreux in West Africa. A retired professional of the European peloton, Ducreux organized the Grand Prix de l’Amitié Franco-Africaine (“The Grand Prix of French-African Friendship”).

This track style race on the streets of Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, showcased the best African athletes against European stars like Bernard Thévenet and Lucien Van Impe. Ducreux coordinated sponsorships for African teams and imported equipment so the locals could compete on par with the Europeans.

These races proved hugely popular and Ducreux turned to promoting stage races in Niger, Togo, Benin, and Burkina Faso. Like their European and American counterparts, these African tours featured time trials, criteriums and road stages up to 170 kilometers. While West Africa lacks the epic mountain climbs of Europe, stifling heat and rough roads made for epic competition.

As cycling grew in West Africa, Saka won countless titles including the 1985 France-Afrique Cup. He retired in 1992 and proceeded to a career as a photographer. He also works part-time for the Peace Corps, servicing the bicycles of nearly 100 volunteers who affectionately call him “Papa Velo”. Few volunteers realize the man truing their wheels is a former cycling legend.

Having retired to focus more on his family, Saka passed the torch of top Beninese cyclist to Fernand Gandaho who would compete in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Gandaho proudly recalls that he was the last black African to hold on to the Olympic peloton. Today Gandaho is the coach of Benin’s national team, and although equipment and funding are scarce, he continues to recruit youngsters into the sport.

While some may say the golden era of African cycling has passed, numerous athletes continue to train and compete. Today there are fewer international competitions but the Tour de Faso remains the pinnacle of the African cycling calendar, showcasing determined local cyclists against elite Europeans. While it is rare for locals to match the Europeans’ endurance, their clever strategy and raw determination have produced notable African victories.

With African governments facing exponential population growth, pandemic disease, and economic instability, bicycle racing lies low on the priority list. While it may seem absurd to have a cycling team in a country where malnutrition and malaria claim thousands of lives and most people live without running water and electricity, the tenacity and bravery of Beninese cyclists serves as inspiration in the face of adversity. Benin’s national team persists on tattered old equipment. Frames get re-welded, shorts get patched up, and the dream lives on.

Coming up next: A look at today’s Beninese national team

Christoph Herby is currently a Peace Corps volunteer in Benin. Prior to trading his cleats for sandals, he raced stateside for Snow Valley and Rite Aid. Nowadays he pushes anaerobic threshold riding singletrack to the nearest bank and playing soccer with local troublemakers. You can follow his adventures at www.QuietGriot.com